The inconspicuous office is in Moscow’s north-eastern suburbs. A sign reads: “Business centre”. Nearby are modern residential blocks and a rambling old cemetery, home to ivy-covered war memorials. The area is where Peter the Great once trained his mighty army.

Inside the six-storey building, a new generation is helping Russian military operations. Its weapons are more advanced than those of Peter the Great’s era: not pikes and halberds, but hacking and disinformation tools.

The software engineers behind these systems are employees of NTC Vulkan. On the surface, it looks like a run-of-the-mill cybersecurity consultancy. However, a leak of secret files from the company has exposed its work bolstering Vladimir Putin’s cyberwarfare capabilities.

Thousands of pages of secret documents reveal how Vulkan’s engineers have worked for Russian military and intelligence agencies to support hacking operations, train operatives before attacks on national infrastructure, spread disinformation and control sections of the internet.

The company’s work is linked to the federal security service or FSB, the domestic spy agency; the operational and intelligence divisions of the armed forces, known as the GOU and GRU; and the SVR, Russia’s foreign intelligence organisation.

One document links a Vulkan cyber-attack tool with the notorious hacking group Sandworm, which the US government said twice caused blackouts in Ukraine, disrupted the Olympics in South Korea and launched NotPetya, the most economically destructive malware in history. Codenamed Scan-V, it scours the internet for vulnerabilities, which are then stored for use in future cyber-attacks.

Another system, known as Amezit, amounts to a blueprint for surveilling and controlling the internet in regions under Russia’s command, and also enables disinformation via fake social media profiles. A third Vulkan-built system – Crystal-2V – is a training program for cyber-operatives in the methods required to bring down rail, air and sea infrastructure. A file explaining the software states: “The level of secrecy of processed and stored information in the product is ‘Top Secret’.”

The Vulkan files, which date from 2016 to 2021, were leaked by an anonymous whistleblower angered by Russia’s war in Ukraine. Such leaks from Moscow are extremely rare. Days after the invasion in February last year, the source approached the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and said the GRU and FSB “hide behind” Vulkan.

“People should know the dangers of this,” the whistleblower said. “Because of the events in Ukraine, I decided to make this information public. The company is doing bad things and the Russian government is cowardly and wrong. I am angry about the invasion of Ukraine and the terrible things that are happening there. I hope you can use this information to show what is happening behind closed doors.”

The source later shared the data and further information with the Munich-based investigative startup Paper Trail Media. For several months, journalists working for 11 media outlets, including the Guardian, Washington Post and Le Monde, have investigated the files in a consortium led by Paper Trail Media and Der Spiegel.

Five western intelligence agencies confirmed the Vulkan files appear to be authentic. The company and the Kremlin did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The leak contains emails, internal documents, project plans, budgets and contracts. They offer insight into the Kremlin’s sweeping efforts in the cyber-realm, at a time when it is pursuing a brutal war against Ukraine. It is not known whether the tools built by Vulkan have been used for real-world attacks, in Ukraine or elsewhere.

But Russian hackers are known to have repeatedly targeted Ukrainian computer networks; a campaign that continues. Since last year’s invasion, Moscow’s missiles have hit Kyiv and other cities, destroying critical infrastructure and leaving the country in the dark.

Analysts say Russia is also engaged in a continual conflict with what it perceives as its enemy, the west, including the US, UK, EU, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, all of which have developed their own classified cyber-offensive capabilities in a digital arms race.

Some documents in the leak contain what appear to be illustrative examples of potential targets. One contains a map showing dots across the US. Another contains the details of a nuclear power station in Switzerland.

One document shows engineers recommending Russia add to its own capabilities by using hacking tools stolen in 2016 from the US National Security Agency and posted online.

John Hultquist, the vice-president of intelligence analysis at the cybersecurity firm Mandiant, which reviewed selections of the material at the request of the consortium, said: “These documents suggest that Russia sees attacks on civilian critical infrastructure and social media manipulation as one and the same mission, which is essentially an attack on the enemy’s will to fight.”

What is Vulkan?

Vulkan’s chief executive, Anton Markov, is a man of middle years, with cropped hair and dark bags around the eyes. Markov founded Vulkan (meaning volcano in English) in 2010, with Alexander Irzhavsky. Both are graduates of St Petersburg’s military academy and have served with the army in the past, rising to captain and major respectively. “They had good contacts in that direction,” one former employee said.

The company is part of Russia’s military-industrial complex. This subterranean world encompasses spy agencies, commercial firms and higher education institutions. Specialists such as programmers and engineers move from one branch to another; secret state actors rely heavily on private sector expertise.

Vulkan launched at a time when Russia was rapidly expanding its cyber-capabilities. Traditionally, the FSB took the lead in cyber affairs. In 2012 Putin appointed the ambitious and energetic Sergei Shoigu as defence minister. Shoigu – who is in charge of Russia’s war in Ukraine – wanted his own cyber-troops, reporting directly to him.

From 2011 Vulkan received special government licences to work on classified military projects and state secrets. It is a mid-sized tech company, with more than 120 staff – about 60 of whom are software developers. It is not known how many private contractors are granted access to such sensitive projects in Russia, but some estimates suggest it is no more than about a dozen.

Vulkan’s corporate culture is more Silicon Valley than spy agency. It has a staff football team, and motivational emails with fitness tips and celebrations of employee birthdays. There is even an upbeat slogan: “Make the world a better place” appears in a glossy promotional video.

Vulkan says it specialises in “information security”; officially, its customers are big Russian state companies. They include Sberbank, the country’s largest bank; the national airline Aeroflot; and Russian railways. “The work was fun. We used the latest technologies,” said one former employee who eventually left after they grew disillusioned with the job.“The people were really clever. And the money was good, well above the usual rate.”

As well as technical expertise, those generous salaries bought the expectation of discretion. Some staff are graduates of Bauman Moscow State Technical University, which has a long history of feeding recruits to the defence ministry. Workflows are organised on principles of strict operational secrecy, with staff never being told what other departments are working on.

The firm’s ethos is patriotic, the leak suggests. On New Year’s Eve in 2019 an employee created a lighthearted Microsoft Excel file with Soviet military music and a picture of a bear. Alongside it were the words: “APT Magma Bear”. The reference is to Russian state hacking groups such as Cozy Bear and Fancy Bear, and appears to point to Vulkan’s own shadowy activities.

Five months later, Markov reminded his workers of Victory Day, a 9 May holiday celebrating the Red Army’s defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945. “This is a significant event in the history of our country,” he told staff. “I grew up on films about the war and had the good fortune to communicate with veterans and to listen to their stories. These people died for us, so we can live in Russia.”

One of Vulkan’s most far-reaching projects was carried out with the blessing of the Kremlin’s most infamous unit of cyberwarriors, known as Sandworm. According to US prosecutors and western governments, over the past decade Sandworm has been responsible for hacking operations on an astonishing scale. It has carried out numerous malign acts: political manipulation, cyber-sabotage, election interference, dumping of emails and leaking.

Sandworm disabled Ukraine’s power grid in 2015. The following year it took part in Russia’s brazen operation to derail the US presidential election. Two of its operatives were indicted for distributing emails stolen from Hillary Clinton’s Democrats using a fake persona, Guccifer 2.0. Then in 2017 Sandworm purloined further data in an attempt to influence the outcome of the French presidential vote, the US says.

That same year the unit unleashed the most consequential cyber-attack in history. Operatives used a bespoke piece of malware called NotPetya. Beginning in Ukraine, NotPetya rapidly spread across the globe. It knocked offline shipping firms, hospitals, postal systems and pharmaceutical manufacturers – a digital onslaught that spilled over from the virtual into the physical world.

The Vulkan files shed light on a piece of digital machinery that could play a part in the next attack unleashed by Sandworm.

A system ‘built for offensive purposes’

A special unit within the GRU’s “main centre for special technologies”, Sandworm is known internally by its field number 74455. This code appears in the Vulkan files as an “approval party” on a technical document. It describes a “data exchange protocol” between an apparently pre-existing military-run database containing intelligence about software and hardware weaknesses, and a new system that Vulkan had been commissioned to help build: Scan-V.

Hacking groups such as Sandworm penetrate computer systems by first looking for weak spots. Scan-V supports that process, conducting automated reconnaissance of potential targets around the world in a hunt for potentially vulnerable servers and network devices. The intelligence is then stored in a data repository, giving hackers an automated means of identifying targets.

Gabby Roncone, another expert with the cybersecurity company Mandiant, gave the analogy of scenes from old military movies where people place “their artillery and troops on the map. They want to understand where the enemy tanks are and where they need to strike first to break through the enemy lines,” she said.

The Scan project was commissioned in May 2018 by the Institute of Engineering Physics, a research facility in the Moscow region closely associated with the GRU. All details were classified. It is not clear whether Sandworm was an intended user of the system, but in May 2020 a team from Vulkan visited a military facility in Khimki, the same city on the outskirts of Moscow where the hacking unit is based, to test the Scan system.

“Scan is definitely built for offensive purposes. It fits comfortably into the organisational structure and the strategic approach of the GRU,” one analyst said after reviewing the documents. “You don’t find network diagrams and design documents like this very often. It really is very intricate stuff.”

The leaked files contain no information about Russian malicious code, or malware, used for hacking operations. But an analyst with Google said that in 2012 the tech firm linked Vulkan to an operation involving a malware known as MiniDuke. The SVR, Russia’s foreign intelligence agency, used MiniDuke in phishing campaigns. The leak shows that an undercover part of the SVR, military unit 33949, contracted Vulkan to work on multiple projects. The company codenamed its client “sanatorium” and “dispensary”.

Internet control, surveillance and disinformation

In 2018, a team of Vulkan employees travelled south to attend the official testing of a sweeping program enabling internet control, surveillance and disinformation. The meeting took place at the FSB-linked Rostov-on-Don Radio Research Institute. It subcontracted Vulkan to help in the creation of the new system, dubbed Amezit, which was also linked in the files to the Russian military.

“A lot of people worked on Amezit. Money and time was invested,” a former employee recalled. “Other companies were involved as well, possibly because the project was so big and important.”

Vulkan played a central role. It won an initial contract to build the Amezit system in 2016 but documents suggest parts of Amezit were still being improved by Vulkan engineers well into 2021, with plans for further development in 2022.

One part of Amezit is domestic-facing, allowing operatives to hijack and take control of the internet if unrest breaks out in a Russian region, or the country gains a stronghold over territory in a rival nation state, such as Ukraine. Internet traffic deemed to be politically harmful can be removed before it has a chance to spread.

A 387-page internal document explains how Amezit works. The military needs physical access to hardware, such as mobile phone towers, and to wireless communications. Once they control transmission, traffic can be intercepted. Military spies can identify people browsing the web, see what they are accessing online, and track information that users are sharing.

Since last year’s invasion, Russia has arrested anti-war protesters and passed punitive laws to prevent public criticism of what Putin calls a “special military operation”. The Vulkan files contain documents linked to an FSB operation to monitor social media usage inside Russia on a gigantic scale, using semantic analysis to spot “hostile” content.

According to a source familiar with Vulkan’s work, the firm developed a bulk collection program for the FSB called Fraction. It combs sites such as Facebook or Odnoklassniki – the Russian equivalent – looking for key words. The aim is to identify potential opposition figures from open source data.

Vulkan staff regularly visited the FSB’s information security centre in Moscow, the agency’s cyber-unit, to consult on the secret program. The building is next to the FSB’s Lubyanka headquarters and a bookshop; the leak reveals the unit’s spies were jokingly nicknamed “book-lovers”.

The development of these secret programs speaks to the paranoia at the heart of Russia’s leadership. It is terrified of street protests and revolution of the kind seen in Ukraine, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. Moscow regards the internet as a crucial weapon in maintaining order. At home, Putin has eliminated his opponents. Dissidents have been locked up; critics such as Alexei Navalny poisoned and jailed.

It is an open question as to whether Amezit systems have been used in occupied Ukraine. In 2014 Russia covertly swallowed the eastern cities of Donetsk and Luhansk. Since last year, it has taken further territory and shut down Ukrainian internet and mobile services in areas it controls. Ukrainian citizens have been forced to connect via Crimea-based telecoms providers, with sim cards handed out in “filtration” camps run by the FSB.

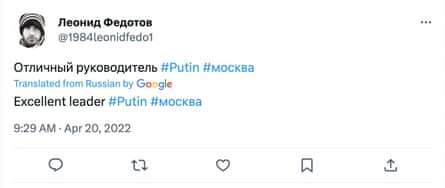

However, reporters were able to track down real-world activity carried out by fake social media accounts linked to Vulkan as part of a sub-system of Amezit, codenamed PRR.

The Kremlin was already known to have made use of its disinformation factory, the St Petersburg-based Internet Research Agency, which has been put on the US sanctions list. The billionaire Yevgeny Prigozhin, Putin’s close ally, is behind the mass manipulation operation. The Vulkan files show how the Russian military hired a private contractor to build similar tools for automated domestic propaganda.

This Amezit sub-system allows the Russian military to carry out large-scale covert disinformation operations on social media and across the internet, through the creation of accounts that resemble real people online, or avatars. The avatars have names and stolen personal photos, which are then cultivated over months to curate a realistic digital footprint.

The leak contains screenshots of fake Twitter accounts and hashtags used by the Russian military from 2014 until earlier this year. They spread disinformation, including a conspiracy theory about Hillary Clinton and a denial that Russia’s bombing of Syria killed civilians. Following the invasion of Ukraine, one Vulkan-linked fake Twitter account posted: “Excellent leader #Putin”.

Another Vulkan-developed project linked to Amezit is far more threatening. Codenamed Crystal-2V, it is a training platform for Russian cyber-operatives. Capable of allowing simultaneous use by up to 30 trainees, it appears to simulate attacks against a range of essential national infrastructure targets: railway lines, electricity stations, airports, waterways, ports and industrial control systems.

An ongoing security risk?

The intrusive and destructive nature of the tools that Vulkan has been hired to build raise difficult questions for software developers who have worked on these projects. Can they be described as cyber-mercenaries? Or Russian spies? Some almost certainly are. Others are perhaps mere cogs in a wider machine, performing important engineering tasks for their country’s cyber-military complex.

Until Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Vulkan staff openly travelled to western Europe, visiting IT and cybersecurity conferences, including a gathering in Sweden, to mingle with delegates from western security firms.

Former Vulkan graduates now live in Germany, Ireland and other EU countries. Some work for global tech corporations. Two are at Amazon Web Services and Siemens. Siemens declined to comment on individual employees but said it took such questions “very seriously”. Amazon said it implemented “strict controls” and that protecting customer data was its “top priority”.

It is unclear if former Vulkan engineers now in the west pose a security risk, and whether they have come to the attention of western counter-intelligence agencies. Most, it would seem, have relatives back in Russia, a vulnerability known to have been used by the FSB to pressure Russian professionals abroad to collaborate.

Contacted by a reporter, one ex-staffer expressed regret at having helped Russia’s military and domestic spy agency. “To begin with it wasn’t clear what my work would be used for,” they said. “Over time I understood that I couldn’t carry on, and that I didn’t want to support the regime. I was afraid something would happen to me, or I would end up in jail.”

There were enormous risks, too, for the anonymous whistleblower behind the Vulkan files. The Russian regime is known for hunting down those it regards as traitors. In their brief exchange with a German journalist, the leaker said they were aware that giving sensitive information to foreign media was dangerous. But they had taken life-changing precautions. They had left their previous life behind, they said, and now existed “as a ghost”.

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER