as universal The Hydrogen-branded plane, powered by the largest hydrogen fuel cell ever to power an airplane, made its first test flight in eastern Washington, co-founder and CEO Paul Eremenko declared the moment the dawn of a “new golden age of aviation”.

The 15-minute test flight of a modified Dash-8 aircraft was short, but it showed that hydrogen could be viable as a fuel for short-hop airliners. That is, if Universal Hydrogen, and others in the emerging world of hydrogen flight, can make the necessary technical and regulatory progress to make it a mainstream product.

A staple at regional airports, Dash-8s typically carry up to 50 passengers on short hauls. The Dash-8 used on Thursday’s test flight from Grant County International Airport in Moses Lake had a decidedly different payload. Universal Hydrogen’s test plane, dubbed the Lightning McClean, had just two pilots, an engineer, and plenty of technology on board, including an electric motor and a hydrogen fuel cell supplied by two other startups.

The disassembled interior contained two racks of electronics and sensors, and two large hydrogen tanks with 30 kg of fuel. Beneath the plane’s right wing, a magniX electric motor was being powered by Plug Power’s new hydrogen fuel cell. This system converts hydrogen into electricity and water, an emissions-free power plant that Eremenko says represents the future of aviation.

The fuel cell ran throughout the flight, generating up to 800 kW of power and producing nothing but water vapor and smiles on the faces of a multitude of Universal Hydrogen engineers and investors.

“We think it’s quite a monumental achievement,” Eremenko said. “It keeps us on track to probably have the first certified hydrogen aircraft in passenger service.”

Aviation currently contributes around 2.5% of global carbon emissions and is projected to grow by 4% per year.

Still using jet fuel

The Universal Hydrogen brand aircraft was also based on jet fuel. Notice the Pratt and Whitney turboprop engine under one wing. Image Credits: harris brand

The test flight, which was successful, does not mean that completely carbon-free aviation is just around the corner.

Under the other wing of the Dash-8 ran a standard Pratt and Whitney turboprop engine (note the difference in the photo above), with about twice the power of the fuel cell side. That redundancy helped pave the way with the FAA, which issued a special experimental airworthiness certificate for Dash-8 tests in early February.

One of the test pilots, Michael Bockler, told TechCrunch that the plane “flew like a normal Dash-8, with just a slight yaw.” He noted that at one point, in level flight, the plane was flying almost entirely on fuel cell power, with the turboprop engine throttled.

“Until both engines are powered by hydrogen, it’s still just show,” said a senior engineer who advises the sustainable aviation industry. “But I don’t want to make fun of it because we need these rungs to learn.”

Part of the problem with today’s fuel cells is that they can be difficult to cool. Jet engines run much hotter, but they expel most of that heat through their exhausts. Because fuel cells use an electrochemical reaction rather than simply burning hydrogen, waste heat must be removed through a system of heat exchangers and vents.

ZeroAvia, another startup developing hydrogen fuel cells for aviation, crashed its first flying prototype in 2021 after shutting down its fuel cell in midair to allow it to cool and then failing to restart it. ZeroAvia has since returned to flying in a similar hydrogen/fossil fuel hybrid configuration as Universal Hydrogen, albeit in a smaller twin-engine aircraft.

Mark Cousin, CTO of Universal Hydrogen, told TechCrunch that his fuel cell could run all day without overheating, thanks to its large air ducts.

Another problem for fuel cell aircraft is storing the hydrogen needed to fly. Even in its densest, supercooled liquid form, hydrogen contains only about a quarter of the energy of a similar volume of jet fuel. The wing tanks are not large enough for the shortest flights, so fuel must be stored inside the fuselage. Today’s 15-minute flight used around 16kg of hydrogen gas, half the amount stored in two motorcycle-sized tanks inside the passenger compartment. Universal Hydrogen plans to convert its test plane to run on liquid hydrogen later this year.

make modules

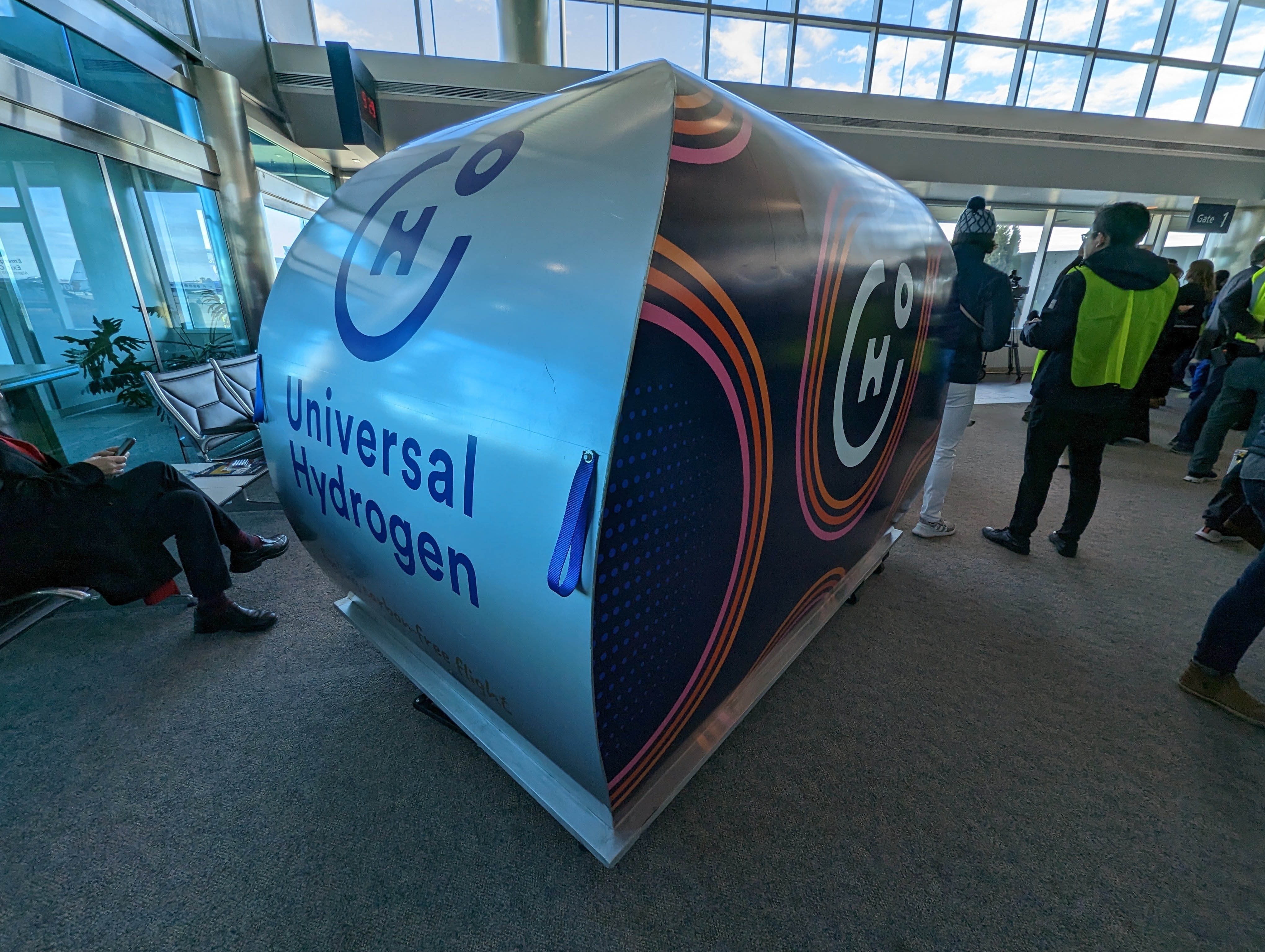

A universal hydrogen module. Image Credits: harris brand

Eremenko co-founded Universal Hydrogen in 2020, and the company raised $20.5 million in a 2021 Series A funding round led by Playground Global. Funding to date is approaching $100 million, including investments from Airbus, General Electric, American Airlines, JetBlue and Toyota. The company is headquartered just down the street from SpaceX in Hawthorne, California, with an engineering facility in Toulouse, France.

Universal Hydrogen will now conduct further testing at Moses Lake. The company will work on developing additional software and will eventually convert the plane to use liquid hydrogen. Early next year, the plane is likely to be retired and the fuel cell headed to the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

Universal Hydrogen expects to start shipping fuel cell conversion kits for regional jets like the Dash-8 as early as 2025. The company already has nearly 250 retrofit orders valued at more than $1 billion from 16 customers, including Air New Zealand. John Thomas, CEO of Connect Airlines, which plans to be the first US airline to use Universal Hydrogen’s technology, said that “the partnership provides the fastest path to zero-emissions operation for the global airline industry.”

Universal Hydrogen doesn’t just make the razors, they also sell the blades.

Almost all of the hydrogen used today is produced at the point of consumption. That’s not only because hydrogen leaks easily and can damage traditional steel containers, but mainly because in its most useful form, a compact liquid, it needs to be kept just 20 degrees above absolute zero, which usually requires expensive refrigeration.

The liquid hydrogen used in the Moses Lake test came from a commercial supplier of “green hydrogen” gas, meaning it was made using renewable energy. Only a small fraction of the hydrogen produced today is produced this way.

If the hydrogen economy is really going to make a dent in the climate crisis, green hydrogen will have to be much easier and cheaper to produce, store and transport.

Eremenko originally started Universal Hydrogen to design standardized hydrogen modules that could be transported by standard semi-trucks and simply placed on aircraft or other vehicles for immediate use. The current design can hold liquid hydrogen for up to 100 hours and has often been compared to the convenience of Nespresso units. Universal Hydrogen says it has more than $2 billion in fuel service orders for the next decade.

The prototype modules were demonstrated in december, and the company expects to break ground on a 630,000-square-foot manufacturing facility for them in Albuquerque, New Mexico later this year. That nearly $400 million project hinges on the success of a previously unreported US Department of Energy loan request of more than $200 million. Eremenko says that the application has passed the first phase of due diligence within the DOE.

a long track

Some experts are skeptical that hydrogen will ever make a significant dent in aviation emissions. Bernard van Dijk, aeronautical scientist at the Hydrogen Science Coalition, appreciates the simplicity of Universal Hydrogen’s modules, but notes that even NASA has trouble controlling hydrogen leaks with their rockets. “You still have to connect the boats to the aircraft. How is everything going to be safe? Because if it leaks and someone lights a match, it’s a recipe for disaster,” he says. “I think they are also underestimating the entire certification process for a new hydrogen powertrain.”

Even when those hurdles are overcome, there is the problem of producing enough green hydrogen using renewable electricity, at a price people are willing to play. “If you want all European flights to run on hydrogen, you would need 89,000 large wind turbines to produce enough hydrogen,” van Dijk says. “They would cover an area about twice the size of the Netherlands.”

But Eremenko remains convinced that Universal Hydrogen and its partners can make it work, with the help of a $3 per kilogram of green hydrogen subsidy in Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act. “Of all the things that keep me up at night,” he says, “the cost and availability of green hydrogen is not one of them.”