earlier this week, the Toyota Research Institute opened the doors of its Bay Area offices to members of the media for the first time. It was a day filled with demos, from driving simulators and drifting instructors to conversations about machine learning and sustainability.

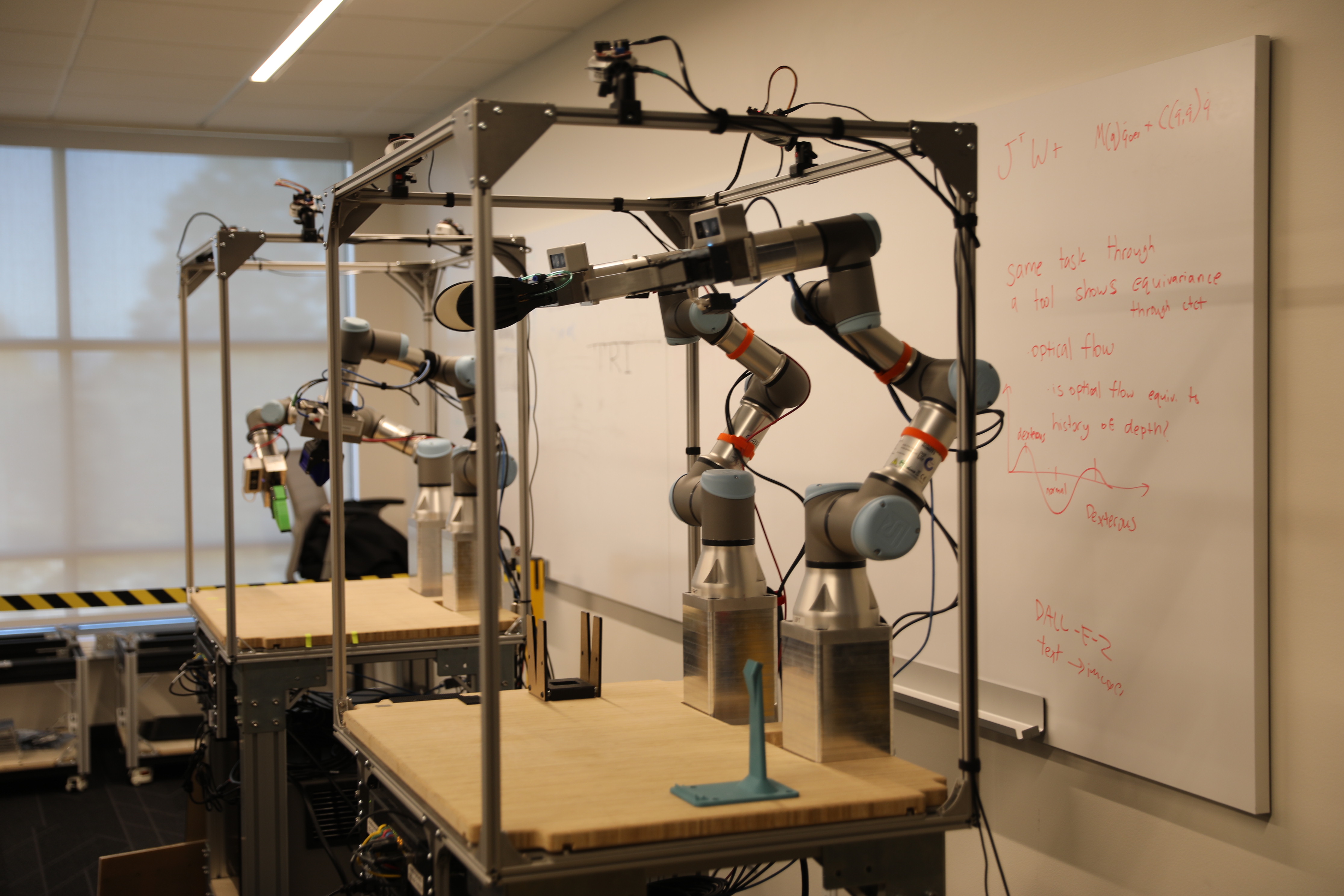

Robotics, a long-standing focus of Toyota’s research division, was also on display. Senior Vice President Max Bajracharya presented a couple of projects. First it was something more like what one would expect from Toyota: an industrial arm with a modified gripper designed for the surprisingly complex task of moving boxes from the back of a truck to nearby conveyor belts, something most factories expect. automate in the future.

The other is a bit more surprising, at least to those who haven’t followed the division’s work so closely. A shopping bot retrieves different products on the shelf based on barcodes and general location. The system can be extended to the top shelf to find items, before determining the best method to grab the wide range of different objects and place them in your basket.

The system is a direct consequence of the 50-person robotics team’s focus on elderly care, aimed at addressing Japan’s aging population. However, it represents a twist away from his original work of building robots designed to perform household tasks like washing dishes and preparing food.

You can read a longer article on that pivot in an article published on TechCrunch earlier this week. That was gleaned from a conversation with Bajracharya, which we’re printing in a fuller statement below. Please note that the text has been edited for clarity and length.

Image Credits: brian heater

TechCrunch: I was hoping to get a demo of the home robot.

Max Bajracharya: We’re still doing some home robot stuff[…] What we have done has changed. Home was one of our original challenge tasks.

Eldercare was the first pillar.

Absolutely. One of the things we learned in that process is that we couldn’t measure our progress very well. The house is so hard. We choose challenging tasks because they are difficult. The problem with the house is not that it was too hard. It was that it was too difficult to measure the progress we were making. We tried many things. We tried to make a mess procedurally. We put flour and rice on the tables and tried to clean them. We put things all over the house to keep the robot tidy. We were deploying to Airbnbs to see how well we were doing, but the problem is that we couldn’t get the same home every time. But if we did, we would fit too much into that house.

Isn’t it ideal that you don’t get the same house every time?

Exactly, but the problem is that we couldn’t measure how well we were doing. Let’s say we were a little better at tidying up this house, we don’t know if that’s because our abilities improved or if that house was a little easier. We were doing the standard, “show a demo, show a cool video. We’re still not good enough, here’s a cool video.” We didn’t know if we were progressing well or not. The supermarket challenge task where we said, we need an environment where it’s as difficult as a home or has the same representative problems as a home, but where we can measure how much progress we’re making.

You’re not talking about specific goals for the home or the supermarket, but for solving problems that can span both places.

Or even measure if we are promoting the state of the art in robotics. Are we capable of perception, movement planning, behaviors that are, in fact, general purpose? To be totally honest, the challenge problem doesn’t matter. DARPA’s robotics challenges were just made-up tasks that were difficult. That is also true for our challenge tasks. We like the home because it is representative of where we eventually want to be helping people at home. But it doesn’t have to be home. The grocery market is a very good representation because it has a great diversity.

Image Credits: brian heater

However, there is a frustration. We know how difficult these challenges are and how far things are, but some random person sees your video and all of a sudden it’s something on the horizon, even if you can’t deliver it.

Absolutely. that’s why gill [Pratt] he says each time, ‘it re-emphasizes why this is a challenging assignment.’

How do you translate that to normal people? Normal people don’t get hung up on challenging tasks.

Exactly, but that’s why in the demo that you saw today, we tried to show the tasks of the challenge, but also an example of how you take the capabilities that come out of that challenge and apply it to a real application, like downloading a container. That is a real problem. We went to the factories and they said: ‘yes, this is a problem. Can you help us?’ And we said, yes, we have technologies that apply to that. So now we’re trying to show that these challenges arise from these few advances that we think are important, and then apply them to real applications. And I think that’s been helping people understand that, because they see that second step.

How big is the robotics team?

The split is about 50 people split evenly between here and Cambridge, Massachusetts.

You have examples like Tesla and Figure, who are trying to make all-purpose humanoid robots. It sounds like you’re headed in a different direction.

A bit. One thing we have observed is that the world is built for humans. If you just have a blank slate, you’re saying that I want to build a robot to work in human spaces. You tend to end up in human proportions and human level capabilities. You end up with human legs and arms, not because that’s necessarily the optimal solution. It’s because the world has been designed around people.

Image Credits: Toyota Research Institute

How are milestones measured? What does success look like for your team?

Moving from the house to the grocery store is a great example of that. We were making progress at home, but not as quickly or as clearly as when we moved to the grocery store. When we move to the grocery store, it really becomes very apparent how well you are doing and what the real problems are in your system. And then you can really focus on solving those problems. When we toured Toyota’s manufacturing and logistics facilities, we saw all these opportunities where they’re basically the challenge of grocery shopping, except they’re a little different. Now, the part instead of the parts being grocery items, the parts are all the parts in a distribution center.

You hear from 1,000 people that you know home robots are really hard, but then you feel like you have to try it yourself and then you like it, really, you make the same mistakes they did.

I think I’m probably just as guilty as everyone else. It’s like, now our GPUs are better. Oh we have machine learning and now you know we can do this. Oh okay, maybe that was harder than we thought.

Something has to tip it at some point.

Maybe. I think it’s going to take a long time. Like automated driving, I don’t think there is a panacea. It’s not just like this magical thing, that’s going to be ‘okay, now we figured it out.’ It’s going to be flaking, flaking, gradually. That’s why it’s important to have that kind of roadmap with shorter timelines, you know, shorter and shorter milestones that give you small milestones, so that you can keep working towards really achieving that long-term vision.

What is the process to actually produce any of these technologies?

That is a very good question that we ourselves are trying to answer. I think we now understand the landscape. Maybe I was naive at first to think that, okay, we just need to find this person that we’re going to pass the technology on to a third party or someone within Toyota. But I think we’ve learned that whatever it is, whether it’s a business unit, a company, a startup, or a unit within Toyota, they don’t seem to exist. So, we’re trying to find a way to create and I think that’s the story of TRI-AD, a little bit too. It was created to take the automated driving research we were doing and translate it into something that was more real. We have the same problem in robotics and in many of the advanced technologies that we work on.

Image Credits: brian heater

You’re thinking about potentially getting to a place where you can have spin-offs.

Potentially. But it’s not the primary mechanism by which we would commercialize the technology.

What is the main mechanism?

we don’t know. The answer is that the diversity of things we do is very likely to be different for different groups.

How has TRI changed since its founding?

When I started, I feel like we were clearly just doing research in robotics. Part of that is because we were a long way from the technology being applicable to almost any challenging real-world application in a human environment. Over the last five years, I feel like we’ve made enough progress on that very challenging problem that we’re now starting to see it develop into these real world applications. We have consciously changed. We’re still pushing 80% of the state of the art with research, but now we’ve allocated maybe 20% of our resources to find out if that research is as good as we think it is and if it can be applied to reality. -global applications. We could fail. We might find that we think we’ve made some cool strides, but it’s just not reliable or fast enough. But we are putting 20% of our effort into trying.

How does care for the elderly fit into this?

I would say that, in a way, it is still our North Star. The projects are still looking at how we ultimately amplify people in their homes. But over time, as we choose these challenging tasks, if things come up that are applicable to these other areas, that’s where we’re using these short-term milestones to show progress in the research that we’re doing.

How realistic is the possibility of a full shutdown factor?

I think if you were able to start from scratch in the future, maybe, that could be a possibility. If I look at current manufacturing, specifically for Toyota, it seems highly unlikely that you’ll be able to get anywhere near that. Us [told factory workers], we are building robotics technology, where do you think it could be applied? They showed us many, many processes where it was things like, you take this wire harness, you run it through here, then you take it out here, then you clip it here, you clip it here and you take it here, and you take it here, and then you you execute like this And this takes a person five days to learn the skill. We said, ‘yeah, that’s too hard for robotic technology.’

But the things that are most difficult for people are the ones that you would like to automate.

Yes, difficult or potentially injury prone. Sure, we’d like to step up to that eventually, but where I look at robotic technology today, we’re pretty far from there.

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER