Ryan Reynolds-backed Mint Mobile exited to T-Mobile for $1.35 billion last year, and Sam Altman-backed “ai Pin” startup Humane launched a pricey little device with a $24 monthly subscription that comes with phone number, unlimited data and as many ai-powered queries as you can muster.

What do they have in common? They’re both MVNOs, short for “mobile virtual network operators” — independent mobile services built on top of carriers’ infrastructure.

MVNOs aren’t new — they’ve been around since the 1990s — but the business model is having a moment. Tapping advances in network and cloud technologies, brands are becoming MVNOs to build direct relationships with their customers and fans through businesses that promise significant recurring revenues and a larger share of wallet than a mere app might get.

“The march of technology has facilitated growth,” James Gray, managing director at telecom industry consultancy Graystone Strategy, told TechCrunch. “The movement towards 100% digital MVNOs and the launch of eSIM has made it much easier and cost-effective to have an all-digital distribution strategy. That’s why we are now seeing growth in new forms of MVNOs.”

Indeed, the global MVNO industry is pegged as an $84 billion market today and its growth is accelerating, with an increase of nearly 40% expected in the next five years to $116.8 billion.

Humane condition

MVNOs were already a “lighter” option for building a carrier from the ground up — they require none of the costly overheads of operating physical infrastructure. But that didn’t always make MVNOs a slam dunk, as the margins made it tough to compete against the main carriers. The advance of technology has changed all that though, and there is software for MVNOs to offer differentiated services and manage the entire stack themselves. And the advent of the eSIM — which negates the need for physical SIM cards — makes it even easier to enter the MVNO space. That is the route Humane has taken.

“Using an eSim offers multiple advantages, ranging from ease-of-activation to ensuring ai Pin can maintain its overall weight, size and shape, which is key for a wearable ai-powered device,” a Humane spokesperson told TechCrunch.

But why assume the responsibility of running its own network, albeit one tied to T-Mobile, when it would be simpler to ask the customer to arrange their own connection? It all comes down to reducing friction, making the ai Pin work out of the box, while allowing Humane to remain firmly in the driving seat.

“By becoming an MVNO, this enables us to control the entire customer experience from end-to-end,” Humane said. “This makes the process for the consumer as simple and intuitive as possible, and enables the network connectivity detail to fade into the background.”

Humane’s ai Pin in action. Image Credits: Humane

Rather than addressing customers as a single entity, MVNOs can tailor their product for any number of differentiated segments. For example, an enterprise CFO might not value a consumer MVNO that ships with free Spotify, but they might fancy a bespoke service that serves deep insights and granular controls over how the plan is deployed among its 50,000 workforce.

Some MVNOs align themselves with ethical issues, as U.K. green energy company Ecotricity does with Ecotalk, a network that promises to invest profits in environmentally-friendly endeavors.

And many carriers build their own sub-brand MVNOs to target different demographics, or they simply acquire existing ones — as T-Mobile did with Mint.

“MVNOs have the flexibility, agility, and business models to react quickly and innovate,” Gray said. “They are well-placed to offer more targeted propositions for different customer segments, or ones that are aligned to customer values. And there are a lot of MVNO-like operator sub-brands launching globally as operators recognize their brands won’t ‘stretch’ to different customer segments.”

Regulation time

Richard Branson launches Virgin Mobile USA Cellular phone service in NYC. July 24, 2002. Image Credits: Evan Agostini/ImageDirect via Getty

The first MVNO arrived back in 1999 with the U.K.’s Virgin Mobile, followed swiftly by a triumvirate in Denmark (Club Blah Blah, Tele2 A/S and Telmore). These initial four grew to more than 300 globally within a decade and 1,300 by 2018. Today, there’s an estimated 2,000 MVNOs across 90 countries, according to mobile network industry body GSM Association (GSMA), with hundreds more set to launch.

This represents a 53% growth in MVNOs in the past five years, pitting the ratio of MVNOs to mobile network operators (MNOs) at well over 2:1. Leading the charge is Europe, constituting half of the global MNVO market, followed by the Americas (19%) and Asia (16%).

Carriers haven’t always loved MVNOs — regulations have variously had to mandate access to would-be competitors, or loosen it up when the economics for carriers got tougher. But as it becomes more difficult for MNOs to reach new customers, they are more inclined to encourage niche players looking to build businesses on top of their infrastructure, serving as a lucrative side-hustle that cashes in on spare network capacity, with the MVNOs picking up all the marketing and distribution costs. It’s a win-win.

Keen to promote competition, governments are broadly in favor of smaller upstarts building on the big guns’ infrastructure. But regulatory requirements vary greatly from market-to-market — some countries mandate that MVNOs provide access, while others “encourage” it.

The role that regulations plays can’t be understated though. Some countries have been slow to embrace the MVNO movement, with the likes of Nigeria recently opening to MVNOs by issuing more than 40 licenses to new networks in the country.

“This is expected to spill into other countries in the region, who have been less proactive on issuing MVNO licenses, or where the traditional operators have a close relationship with the regulator,” Allan T. Rasmussen, a telecoms industry consultant, analyst and MVNO specialist explained to TechCrunch. “These countries will have to adapt sooner than later, so they’re not be left behind in the digital economy.”

Still, some jurisdictions make it difficult for MVNOs — Pakistan has made it prohibitively expensive, charging a whopping $5 million just to obtain a license. And Canada has historically insisted that any MVNO must have its own infrastructure, which goes against the whole MVNO concept and means that any MVNO has been a big telco sub-brand.

So while the MVNO landscape does vary, regulators and big telcos generally favor the model as they are pro-competition and are an effective way to monetize spare network capacity.

Hearts and minds

Roccstar attends the DJ Drama listening party. Image Credits: Erik Voake for MNRK Music Group / Getty

Long-gone are the days when MVNOs can compete with the major telcos on price — they have to bring something unique to the table, through tailored products that appeal to the hearts and minds of a specific audience.

Mint Mobile became online-only and went to great lengths to explain how it could pass these cost-savings to the customer. Ryan Reynolds’ marketing acumen and gravitas was pivotal to Mint’s rise.

“Despite Reynolds’ popularity, it was a David vs. Goliath story — everyone loves an underdog and they managed to get the message across that with the ‘big guys,’ you are overpaying for a service,” Rasmussen said. “It’s also a prime example of using ‘existing assets’ to sell much more than something boring like telephony — they sold a lifestyle and a sense of ‘I want to be part of this’.”

In a similar vein, Grammy-nominated music producer Leon “Roccstar” Youngblood Jr. recently launched Roccstar Wireless atop T-Mobile, with the “backing of A-list celebrities” (these will apparently remain undisclosed for now).

Roccstar Wireless co-founder Darius Allen, who designed one of the first dual-screen smartphones, says that it’s tapping Mint Mobile’s “branding and experience” playbook to stand out in an increasingly crowded market.

“The success of Mint Mobile wasn’t solely due to its celebrity partners, but it was the marketing team’s execution,” Allen told TechCrunch. “Although we have taken a few pages from the success of Mint, we understand that it’s much bigger than slapping a few celebrities on a network to get users to change carriers. Mint was primarily an online company — we already have more than 2,000 retail distribution partners and over 1,000 independent sales reps.”

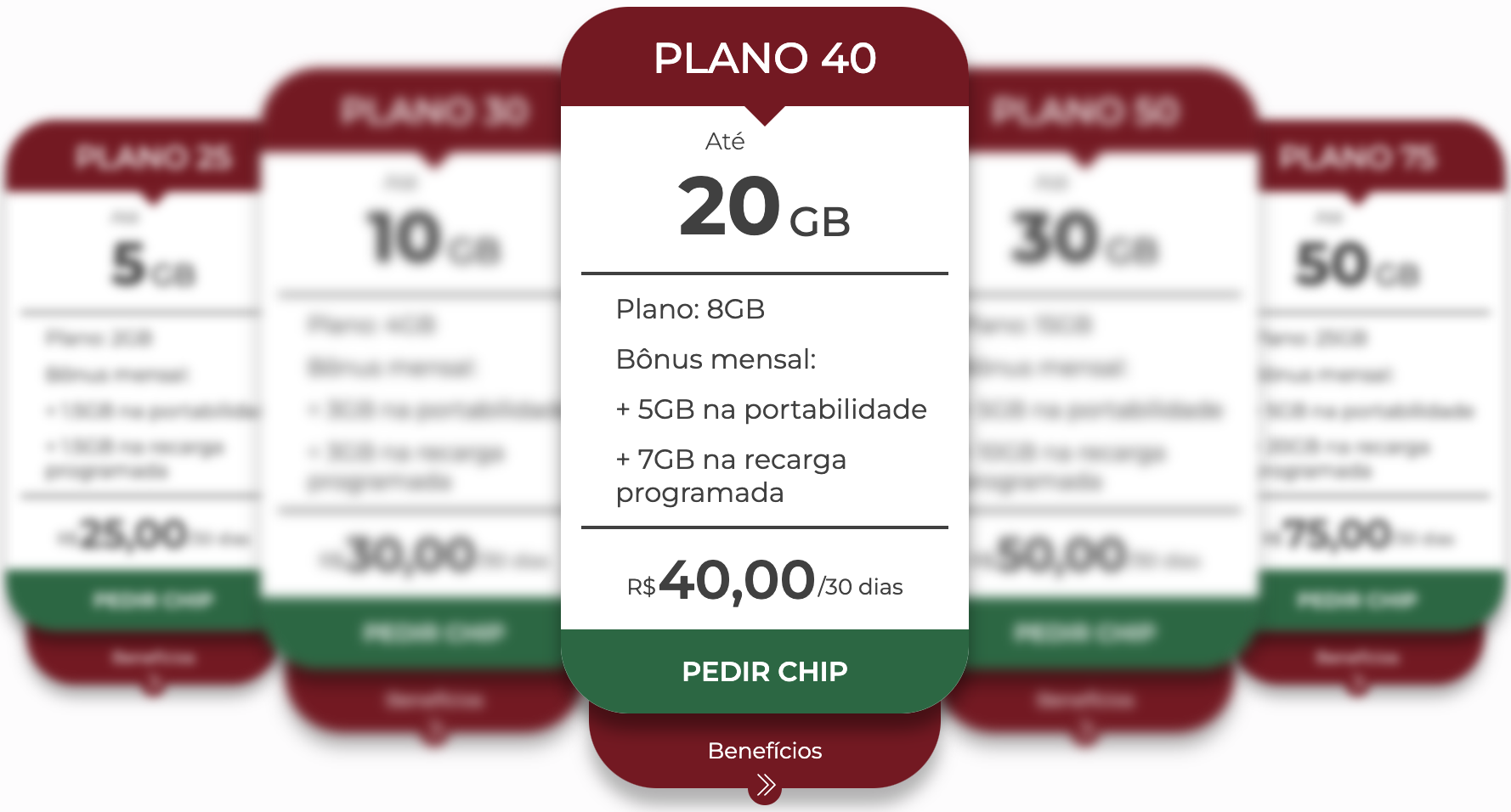

Numerous teams in Brazil’s Série A soccer league have also launched their own-brand mobile networks, with very little difference between their respective plans — Santos, Fluminese and Botafogo are almost exactly identical. All that matters is the brand.

Santos mobile phone plan. Image Credits: Santos FC

Fluminese mobile phone plan. Image Credits: FluMobile

Still, it’s a winning play, with more teams keen to join the MVNO party. In Europe, Turkey’s multi-sport club Fenerbahçe has operated Fenercell since 2009, and last year it was joined by Austrian top-tier soccer club Austria Wien and Italy’s AC Milan, which rolled out AC Milan Connect at the end of October.

There’s nothing stopping anyone from becoming an MVNO if they have enough of a fanbase, from sports teams to YouTubers. But while the process of becoming an MVNO has gotten easier, it is still fraught with challenges.

The enablers

Google has operated an MVNO for eight years, but it has the resources to negotiate partnerships and develop significant facets of the software stack in-house. Smaller entities might not have that luxury, which is where mobile virtual network enablers (MVNEs) really come into play.

MVNEs serve as the bridge between the MVNO and the carrier, taking care of the infrastructure such as SIM card provisioning, billing, user management, customer support, analytics and even front-end consumer-facing apps.

Humane, for example, is working with an MVNE partner called Optiva, which serves the telecom industry with full-stack business support systems such as billing and network integration, though Humane takes care of some things itself. “The front-end, and much of the custom functionality, is built ourselves to fully align with the Humane design and experience,” Humane explained to TechCrunch.

Indeed, companies can decide how much of an “MVNO” they want to be, depending on budgets, goals and technical nous. There are so-called “thin” or “light” MVNOs, which are effectively resellers that rely on carriers’ own resources. Some operators exist somewhere in the middle, with some of their own technology operating under the hood, before we arrive at MVNOs, which are fully fledged mobile networks sans mobile mast.

These full-stack MNVOs are becoming more common for various reasons, such as the availability of tools that give access to every element of the stack, such as deep packet inspection (DPI) that provides granular controls over permitted content. For instance, a kid-focused MVNO might want to enable parents to block access to TikTok after a certain time, or allow customers to access specific domains when they have no credit.

By way of example, Uber launched an MVNO in Mexico last year (it had operated one in Brazil since 2021), a move designed to address affordability among its vast driver base. With Uber Cel, the ride-hail giant makes it cheaper to access services that help the driver do their job, including unlimited use of the Uber app, Google Maps or Waze.

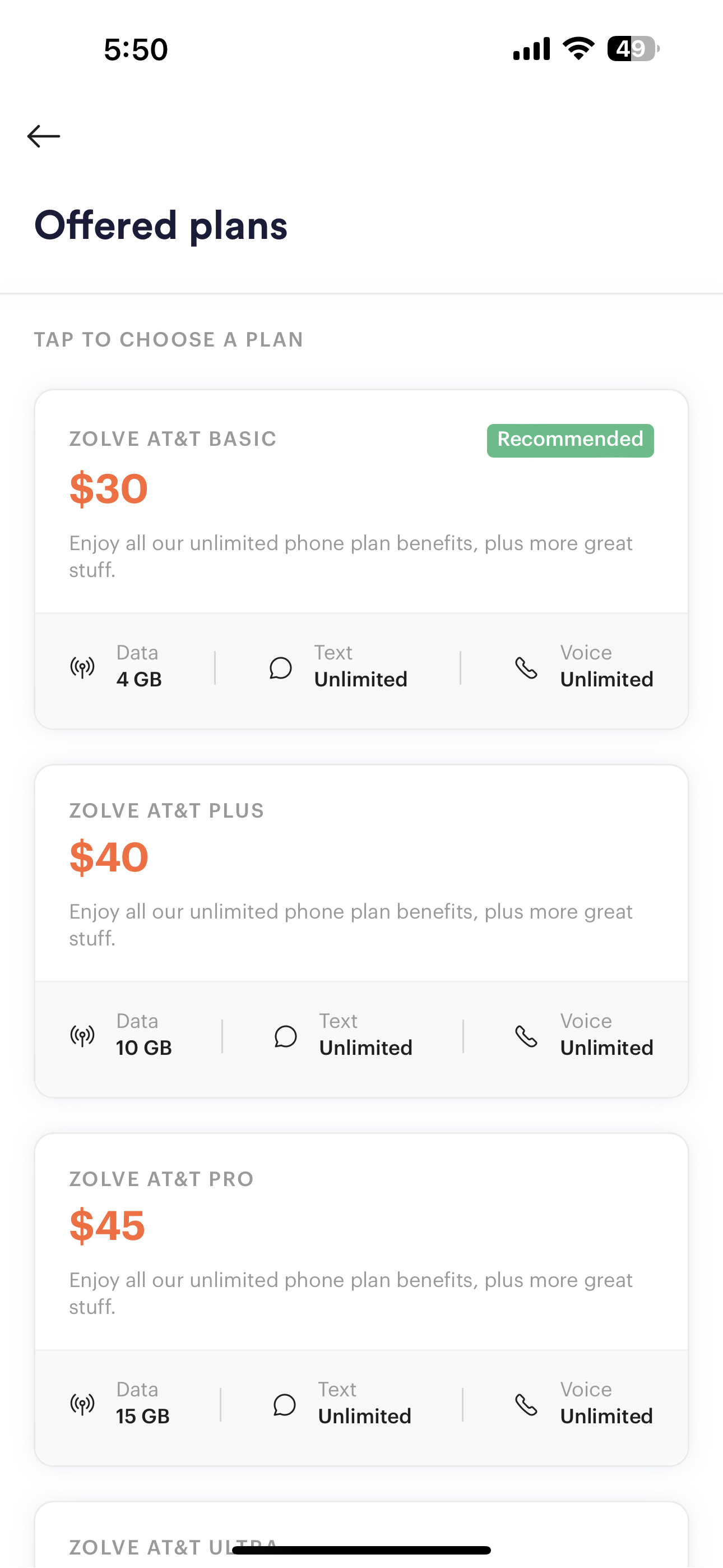

Zolve — an Indian neobank that helps immigrants set up banking before they arrive in the U.S. — entered the MVNO market last year too. Hurdles that immigrants face with banking are similar to those of getting a mobile phone plan, with weeks or months of red-tape, paper work and approval processes often delaying matters.

“SIM Cards perfectly fit that story, as another essential service which immigrants need to settle faster and hence we deliver them in their home country,” Prudhvi Varma, Zolve’s head of marketing, explained to TechCrunch. “Otherwise, immigrants have to take temporary travel SIM cards or take international roaming services which are costly with limited validity before they get their own plans in the U.S.”

Users can signup for their phone plan from anywhere in just a few minutes, with a choice of AT&T or T-Mobile.

Zolve mobile phone plan. Image Credits: Zolve

Initially, Zolve explored all the usual channels that budding-MVNOs go through. This included trying the “reseller” route, which involves partnering with an MNO to create own-brand SIM cards, with the carrier taking care of the underlying spadework. But this would have positioned Zolve more as a distribution channel for the carrier, plus it wouldn’t give Zolve much control over the experience or access to any data.

“It was all a broken experience for customers as they have to visit Zolve to get a (SIM) activation code, create separate accounts with the telecom provider, and so on,” Varma said. “For Zolve, it was difficult to track SIM activations, invoicing and such like.”

So Zolve turned to Gigs to provide all the underlying infrastructure — Gigs is basically an MVNO in a box, giving companies everything they need to offer telephony services natively, including checkouts, multicurrency payments and a single API that connects to multiple carriers. Gigs raised $20 million last year from notable backers, including Google’s Gradient Ventures.

Behind the scenes, Gigs buys huge volumes of data, voice and SMS capacity from the telecom providers, collates their APIs into a single layer, and businesses can construct their own phone plans as required. The platform also offers customer and subscription-management smarts, with data presented in a single dashboard giving a full view of subscriptions, payments and analytics.

Gigs Dashboard. Image Credits: Gigs

This “plug and play” approach is why Gigs touts itself as a “Stripe for phone plans.”

“When Stripe came along, everybody could put a payment button in front of anything in a matter of hours or days, and you could get a full integration of payments done with a team in a couple of weeks,” Gigs CEO Hermann Frank told TechCrunch. “No need to talk to the banks or the acquirers, and no need to build everything from scratch while spending millions.”

Gigs recently announced an ai product for MVNOs called Operator, designed to reduce customer support overhead by up to 95%.

The ChatGPT-powered service allows end-users to self-serve just about any request — this includes UI elements to facilitate requests directly inside a chat. For instance, if a subscriber wants to update their credit card information, or if they need an eSIM for a new phone, Gigs will enable this there and then.

“We’re able to do this because we’re fully vertically integrated right into the network and into our own stack,” Frank said.

Gigs Operator. Image Credits: Gigs

Recurring revenue

U.S. hardware startup Light also functions as an MVNO, with the minimalist phonemaker offering mobile plans for several years. But it was far from plain-sailing at first, having to use different platforms for different aspects of its network. Thus, Light quietly switched to Gigs a few months back.

“Even just from an admin perspective, we’re now able to see everything about each user in the one dashboard, such as whether their card was declined,” Light co-founder Joe Hollier told TechCrunch. “There’s now so much more automation for things that were once manual — every month we would (previously) manually email people whose cards had been declined!”

The minimalist Light phone also offers its own mobile plans. Image Credits: Light

While simplicity and affordability were among the motives behind Light’s mobile plans, it also gives customers another way to support its mission — to create a sustainable business off the back of a minimalist mobile phone.

“We do have a really strong and grassroots community, and so the additional revenue that we make off the service plan we invest back into our software development and so on,” Hollier said. “Users are excited to pay versus any of these other carriers, and the revenue from the Light Plan has been a way for people to support us.”

While Hollier said that the bulk of its revenue still comes from physical hardware sales, he hopes the balance might shift. Overhauling its MVNO infrastructure not only makes it easier on the internal administration side, it also improves user-facing features such as SIM card activation and onboarding.

“The easier it is to activate a SIM, the more likely someone’s going to convert,” Hollier said. “As the steps get more tedious, you lose people along the way. We suspect that we’re going to see more activations.”

As we’ve seen with Apple’s increased reliance on services revenue, companies love steady subscription income. And this also could explain why Humane has ventured into MVNO territory — generating revenue on hardware, no matter how fancy and futuristic, is difficult. It’s rare for a company to scale the mountain of unit economics, making it risky to depend on that alone for a sustainable business.

“The patents and licensing fees will eat up what little there might be left after producing the device,” Rasmussen said. “A subscription-based model will not only keep the customers in the loop, but also provide a recurring revenue stream. In return, Humane will get the user data that comes with telephony, which they can use to better target the end-users needs and lifestyles. Humane will thus be in control of managing both the device and signal for current services and new opportunities, without having to pass through a mobile operator first.”