In April 2022, Elon Musk acquired a 9.2% stake in Twitter, making him the company’s largest shareholder, and was offered a seat on the board. Luke Simon, a senior engineering director at Twitter, was ecstatic. “Elon Musk is a brilliant engineer and scientist, and he has a track record of having a Midas touch when it comes to growing the companies he’s helped lead,” he wrote on the workplace messaging platform Slack.

Twitter had been defined by the leadership of Jack Dorsey – a co-founder who was known for going on long meditation retreats, fasting 22 hours a day, and walking five miles to the office – who was seen by some as an absentee landlord, leaving Twitter’s strategy and daily operations to a handful of trusted deputies. To Simon and those like him, it was hard to see Twitter as anything other than wasted potential.

In its early days, when Twitter was at its most Twittery, circa 2012, executives called the company “the free-speech wing of the free-speech party”. That was the era when the platform was credited for amplifying the Occupy Wall Street movement and the Arab spring, when it seemed like giving everyone a microphone might actually bring down dictatorships and right the wrongs of neoliberal capitalism.

Frequently, the platform set the news agenda. What it lacked in profits it more than made up for in influence. No one understood how to weaponise that influence better than Donald Trump, who in 2016 propelled himself into the White House in part by harnessing hate and vitriol via his @realDonaldTrump feed. A new consensus that the site was a sewer made it worth a lot less money.

Musk had offered to buy the company for the absurdly inflated price of $44bn. The move thrilled employees like Simon who chafed at Twitter’s laidback atmosphere and reputation for developing new features at a glacial pace.

Other employees noted the darker motifs of Musk’s career – the disregard for labour relations, the many current lawsuits alleging sexual harassment and racial discrimination at his companies – and found his interest in Twitter ominous. On Slack, a product manager responded to Simon’s enthusiasm for Musk with scepticism: “I take your point, but as a childhood Greek mythology nerd, I feel it is important to point out that the story behind the idea of the Midas touch is not a positive one. It’s a cautionary tale about what is lost when you only focus on wealth.”

The comment would prove to be prophetic. According to more than two dozen current and former Twitter staffers, Musk has, since buying the company in October 2022, shown a remarkable lack of interest in the people and processes that make his new toy tick. He has purged thousands of employees, implemented ill-advised policies, and angered even some of his most loyal supporters.

If “free speech” was his mandate for Twitter the platform, it has been the opposite for Twitter the workplace. Dissenting opinion or criticism has led to swift dismissals. Musk replaced Twitter’s old culture with one of his own, but it’s unclear, with so few workers and plummeting revenues, whether or not this new version will survive.

On 26 October 2022, an engineer – let’s call her Alicia – sat in a glass conference room in San Francisco trying to explain the details of Twitter’s tech stack to Elon Musk. He was supposed to officially buy the company in two days, and Alicia and a small group of trusted colleagues were tasked with outlining how its core infrastructure worked. But Musk, who was sitting two seats away from Alicia with his elbows propped on the table, looked sleepy. When he did talk, it was to ask questions about cost. How much does Twitter spend on data centres? Why was everything so expensive?

Fine, she thought. If Musk wants to know about money, I’ll tell him. She launched into a technical explanation of the company’s data-centre efficiency, curious to see if he would follow. Instead, he interrupted. “I was writing C programs in the 90s,” he said dismissively. “I understand how computers work.”

David Sacks, a venture capitalist and friend of Musk’s who had advised him on the acquisition, walked into the room.

“David, this meeting is too technical for you,” Musk said, waving his hand to dismiss Sacks. Wordlessly, Sacks turned and walked out, leaving the engineers in the room – who had received little engagement from Musk on anything technical – slack-jawed. His imperiousness in the middle of a session he appeared to be botching was something to behold. (Sacks disputes this account of the meeting.)

The next day, Alicia and her colleagues gathered in the cafeteria of Twitter’s San Francisco headquarters for a long-planned Halloween party. The room was decorated with miniature pumpkins and fake spiderwebs. Employees tried to get in the holiday spirit, but rumours were swirling that Musk planned to cut 75% of the company. People were sobbing in the bathrooms. One company leader recalled the surreal moment of crying about the end of Twitter as they knew it, only to look up and see a person in a Jack Sparrow costume amble by.

The days surrounding the acquisition passed in a blur of ominous, unlikely scenes. Musk posing as the world’s richest prop comic, announcing his takeover by lugging a kitchen sink into the office: “Entering Twitter HQ – let that sink in!” (181.2k retweets, 43.6k quote tweets, 1.3m likes). A fleet of Teslas in the parking lot. Musk’s intimidating security detail standing outside his glass conference room as if guarding the leader of a developing nation. Musk’s two-year-old son, X Æ A-Xii, toddling around the second floor, occasionally crying.

Employees braced for layoffs, but no word came from Musk. People hunted for information on their unofficial chats while glued, like everyone else, to Musk’s Twitter feed for news. “Hey all don’t forget to complete your q3 goals!” one employee wrote darkly on Slack. “Writes, ‘stay employed,’” responded a colleague.

Musk brought in a cadre of close advisers, including Sacks – to employees, this crew would be known by only one name: the Goons.

On Musk’s first full day in charge, 28 October, the executive assistants sent Twitter engineers a Slack message at the behest of the Goons: the boss wanted to see their code. Employees were instructed to “print out 50 pages of code you’ve done in the last 30 days” and get ready to show it to Musk in person. Panicked engineers started hunting around the office for printers.

Within a couple of hours, the Goons’ assistants sent out a new missive to the team: “UPDATE: Stop printing,” it read. “Please be ready to show your recent code (within last 30-60 [days] preferably) on your computer. If you have already printed, please shred in the bins on SF-Tenth. Thank you!”

The botched code review did little to deter the Goons, who still needed to figure out which of Twitter’s 7,500 employees were needed to keep the site running – and who could be jettisoned. At 10 that same night, they told managers they should “stack rank” their teams, a common but cold method of evaluation that forces managers to designate their lowest performers.

Amir Shevat, who managed Twitter’s developer platform and had led large teams at Amazon, Google, and Microsoft, was perplexed. Every company did stack ranking differently. Should they sort workers by seniority? Impact? Revenue generated? No one had an answer. “They said, ‘We don’t know. Elon wants a stack rank,’” Shevat says.

The project succeeded in generating large lists of names, but because different managers had ranked employees according to their own methods, the results were incoherent.

Meanwhile, managers were fielding worried questions from workers, but the only one that mattered – “Will I still have a job here?” – no one could answer. Even Shevat didn’t know if his position was safe.

The following week, on 3 November, employees received an unsigned email from “Twitter” relaying that the time for layoffs had started. By 9am the following day, everyone would receive a note telling them whether they still had a job.

That night, hundreds of employees gathered in a Slack channel called #social-watercooler, which had become the company’s de facto town square since Musk took over. They posted salute emoji and blue hearts – solidarity for those who were being cut and for those who deeply wanted to be shown the door but were somehow asked to stay. One person posted a meme of Thanos from Avengers: Infinity War, the supervillain who exterminates half the living beings in the universe with a snap.

By morning, half the workforce had lost their jobs, well over 3,000 people. The layoffs wiped out Shevat and his entire team. Alicia kept her position, but was left with survivor’s guilt. She started quietly encouraging her workers to prepare an exit strategy.

Moments of institutional chaos are always someone’s opportunity, and at Twitter, that person was a product manager named Esther Crawford. Before the takeover, Crawford had been focused on products that let creators make money from their Twitter accounts. When Musk arrived, she began angling for a bigger role and soon was pitching him on various ways Twitter could be improved.

It worked: Crawford was tasked with relaunching Twitter’s subscription product, Twitter Blue. Musk had made it clear he wanted to do away with Twitter’s old verification method, which he called a “lords and peasants system”. To be verified – a symbol that an account had been vetted as authentic – a user had to be approved by someone at Twitter. Blue check marks mostly went to brands, celebrities, and journalists, reinforcing Musk’s belief that the platform was tilted in favour of media elites.

To correct this imbalance, Musk wanted to implement a crude pay-to-play scheme. After originally proposing to charge $20 a month for verification, he was talked down to $8 after Stephen King tweeted at his 7 million followers: “$20 a month to keep my blue check? Fuck that, they should pay me. If that gets instituted, I’m gone like Enron.”

Twitter’s trust and safety team compiled a seven-page document outlining the dangers associated with paid verification. What would stop people from impersonating politicians or brands? They ranked the risk a “P0”, the highest possible. But Musk and his team refused to take any recommendations that would delay the launch. In early November, Crawford posted a picture of herself in an eye mask and sleeping bag at the office: “When your team is pushing round the clock to make deadlines sometimes you #SleepWhereYouWork,” she said.

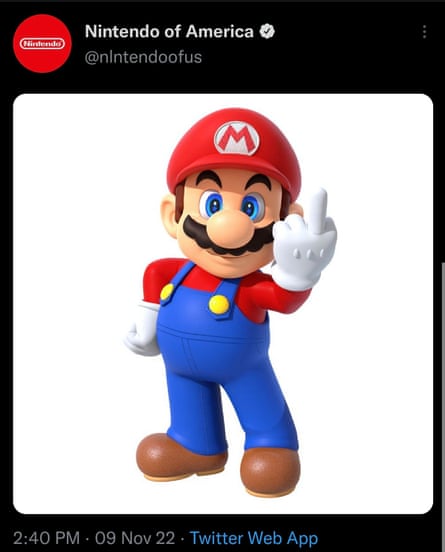

Twitter Blue’s paid verification system was unveiled on 5 November. Almost immediately, fake verified accounts flooded the platform. An image of Mario giving the middle finger from what looked like the official Nintendo account stayed up for more than a day. An account masquerading as the drug manufacturer Eli Lilly tweeted that insulin would now be free; company executives begged Twitter to take down the tweet. The marketing team tried to do damage control. “You build trust by being transparent, predictable, and thoughtful,” one former employee says. “We were none of those with this launch.”

Days after the subscription service debuted, Twitter canned it. Yoel Roth, the head of the team whose warnings had been ignored, resigned.

Musk’s blundering left a deep scar. Twitter Blue was meant to begin shifting Twitter’s revenue away from ads toward subscriptions. But while chasing a relatively paltry new cash stream, Musk torched the company’s ad business – the source of the vast majority of its billions in revenue. The Blue disaster accelerated a rush of advertisers abandoning the platform, including pharmaceuticals giant Eli Lilly, and by December, what was left of Twitter’s sales team began offering hundreds of thousands of dollars in free ad spend to lure back marketers.

In a series of tweets, Musk blamed the company’s “massive drop in revenue” on “activist groups pressuring advertisers”. To Musk, it was anyone’s fault but his own.

On 10 November, with just 20 minutes’ notice, Musk gathered his remaining employees to address them directly for the first time. He spoke frankly about the state of the business and suggested even more layoffs were to come. He also revoked a policy that had promised the entire staff the freedom to work remotely, forever, if they wished. “Basically, if you can show up in an office and you do not show up at the office, resignation accepted. End of story,” he said.

Slack and Signal erupted. A lawyer pointed out that this would be a fundamental change to their employment contracts, and employees did not have “an obligation to return to office”.

Alicia decided she had had enough. She enjoyed working from the office but felt that forcing employees to do so, and on such short notice, was immoral. She told colleagues not to resign. “Let him fire you,” she said. Why give Musk what he wanted? Five days later, she was fired.

On 16 November, Musk emailed his remaining 2,900 employees an ultimatum. He was building Twitter 2.0, he said, and workers would need to be “extremely hardcore”, logging “long hours at high intensity”. The old way of doing business was out. Now, “only exceptional performance will constitute a passing grade”. He asked employees to sign a pledge through Google Forms committing to the new standard by the end of the next workday.

But who wanted that? Employees were still waiting to be given a coherent vision for what Twitter 2.0 could be. Employees knew what Musk didn’t want – content moderation, free gourmet lunches, people working from home – but had few clues as to what he did want. Besides, was being fired for not checking a box on a Google Form even legal?

By December, more than half the staff was gone. Remaining employees were warned not to take long Christmas vacations. Just when morale seemed to be bottoming out, Musk began doxing [publishing private information online] their colleagues.

Only a small inner circle knew Musk had invited the journalist Matt Taibbi to comb through internal documents and publish what he called “the Twitter Files”. The intention seemed to be to give credence to the notion that Twitter is in bed with the deep state, beholden to the clandestine conspiracies of Democrats. “Twitter is both a social media company and a crime scene,” Musk tweeted.

In an impossible-to-follow tweet thread that unfolded over several hours, Taibbi published the names and emails of rank and file ex-employees involved in communications with government officials, insinuating that Twitter had suppressed the New York Post story about Hunter Biden’s laptop. After it was pointed out that Taibbi had published the personal email of Jack Dorsey, that tweet was deleted, but not the tweets naming low-level employees or the personal email of a sitting congressman.

Employees rushed to warn a Twitter operations analyst whom Taibbi had doxed to privatise her social media accounts, knowing she was about to face a deluge of abuse.

While his journalists were putting former employees at risk, Musk bent the company’s free speech policies to protect himself. After one of his children was allegedly stalked by a fan in South Pasadena, Musk blamed a Twitter account that tracked public data about the whereabouts of his private jet – his “assassination coordinates”, Musk said. He then suspended @ElonJet account, the account of its owner, and dozens of others that tracked celebrities’ planes. Several journalists from CNN, the New York Times and elsewhere were suspended for tweeting the news.

One of Musk’s other Twitter Files journalists, Bari Weiss, denounced the crackdown: “The old regime at Twitter governed by its own whims and biases and it sure looks like the new regime has the same problem. I oppose it in both cases.” Musk responded by unfollowing her.

Twitter continues to haemorrhage money, so much so that Musk has stopped paying its bills. The landlords of Twitter offices in San Francisco and London are suing over unpaid rent. And this month Twitter has been auctioning office furniture.

@realDonaldTrump feed. Photograph: Alex Brandon/AP

On Christmas Eve, Twitter abruptly shut down a data centre in Sacramento, California; it also announced it would significantly downsize a data centre in Atlanta, Georgia. Engineers struggled to keep the service running. Outages would happen sporadically, the worst one in January, when the site was down for more than 12 hours for users in Australia and New Zealand. But it was nothing near the catastrophe Musk’s critics had predicted. Twitter Blue was relaunched and mostly, the platform kept humming along.

Late in December, Twitter employees noticed a prominent face was gone from Slack: Luke Simon had left the company. No one knew why. Some joked darkly that kissing Musk’s ring wasn’t enough to keep anyone safe any more. Simon’s Twitter account no longer exists.

The repercussions for Musk’s handling of Twitter are now coming. According to his public-merger agreement and internal Twitter documents, Musk agreed to at least match the company’s existing severance package, which offered two months’ pay as well as other valuable benefits. Instead, he laid off employees with the minimum notice required by federal and state law and refused to pay out certain awards. Now more than 500 employees, with Shevat among the highest-ranking, are pursuing legal action against Musk for what they are owed, in addition to his alleged discrimination against minority groups in his handling of the layoffs.

“I think leadership doesn’t end after you get fired,” says Shevat, adding that he was already paid out for the acquisition of his startup and isn’t doing this for the money.

Musk himself is starting to appear defeated. Tesla shares started 2022 trading at nearly $400. By September, Tesla’s stock price had dropped by 25%. It plummeted again after Musk bought Twitter and ended the year at $123. Investors are begging Musk to step away; Tesla employees are too. As one person on Musk’s transition team put it, “What the fuck does this have to do with cars?”

Musk claims he always intended to be Twitter’s CEO only temporarily. With the damage he has done in three months – to the company and to his own wealth – those watching the nosedive, whether with horror or schadenfreude, can’t help but wonder how much longer he can wait. His failures at Twitter have already damaged his reputation as a genius. How smart could he really be, the guy who purchased a company for far more than it was worth, then drove what remained of it into the ground?

As the year came to a close, Musk’s public statements about Twitter veered from pride in the site’s usage metrics (all-time highs, he regularly assured followers) to what might have been more sober self-assessments of his predicament. “Don’t be the clown on the clown car!” he tweeted on 27 December. “Too late haha.”

If he seemed certain of anything, it was the steadily improving technical architecture of Twitter itself. The staff might be vastly diminished, but what it lacked in size it more than made up for in growing technical competence. Bit by bit, Musk said, Twitter’s notoriously fragile infrastructure was improving.

In some ways, Musk was vindicated. Twitter was less stable now, but the platform survived and mostly functioned even with the majority of employees gone. He had promised to rightsize a bloated company, and now it operated on minimal headcount.

But Musk appears unaware of what he’s actually broken: the company culture that built Twitter into one of the world’s most influential social networks, the policies that attempted to keep that platform safe, and the trust of users who populate it every day with their conversations, breaking news, and weird jokes – Twitter’s true value and contributions to the world.

“Fractal of Rube Goldberg machines… is what it feels like understanding how Twitter works,” Musk wrote in a short thread on Christmas Eve. “And yet work it does… Even after I disconnected one of the more sensitive server racks.”

Four days later, Twitter crashed. More than 10,000 users, many of them international, submitted reports of problems accessing the site. Some got an error message reading: “Something went wrong, but don’t fret – it’s not your fault.”

“Can anyone see this or is Twitter broken,” one user tweeted into the apparent void.

But in that moment, Musk found that whatever might be happening in the world at large – to his site, his other companies, his reputation and legacy – that tweet, at least, appeared on his screen as intended.

“Works for me,” he replied.

This is an edited extract of an article that first appeared in New York magazine and The Verge.

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER