In the first half of the 2010s, when smartphones became ubiquitous, mobile gaming was an exciting new terrain for developers and gamers alike. Here was a new platform, suddenly, in everyone’s pocket, with a touch screen that was much easier to use than a controller, and an integrated audience of millions. There were new and interesting games, perhaps for a few pounds, much more affordable, designed to fit into those small spaces in your life, on the train, at the bus stop, on your lunch break (and, make no mistake, while you hide from your family in the bathroom).

iPhone hits like Angry Birds, Cut the Rope, Clash of Clans, and Crossy Road became some of the biggest hits on the App Store, something Apple itself seemed baffled at the time. And it employed talented developers: Simogo, creators of the wonderfully spooky Year Walk and the elegantly mind-bending mystery game Device 6; Kairosoft and its lovely and immersive simulation games like Game Dev Story; Terry Cavanagh’s Super Hexagon; Ustwo and Monument Valley; Superbrothers: Sword and Sworcery EP. I played so many fun, exciting, and experimental things on phones in the early years of the mobile gaming boom.

Today, however, if you were an indie developer with an innovative idea, you would be crazy to launch it on the App Store. It would be drowned out by thousands of competitive games, including a deluge of knockoffs and cheap junk. Smartphone gaming is now dominated by a couple of perennial money makers, Candy Crush among them, and a few companies that score most of the biggest hits. Indie developers have largely returned to PC and consoles, and what’s left in the app stores is a slew of suspicious-looking free games whose quality is impossible to discern.

If you have kids with access to a phone or tablet, you’ll be familiar with the sheer volume of utter garbage on mobile store windows, ranging from the pirate Pac-Man to mildly disturbing dental procedure games to aggressively cute virtual pet games. They ask you for money every 35 seconds. There’s still some great stuff in there, but it’s gotten hard to find.

Half of the gaming industry’s revenue comes from people playing games on mobile, and we all know these aren’t people paying £3.59 for a full, discrete experience. They’re the people who spend £10 (or £100) a month on cosmetic items, random rewards, or virtual currency to get around the artificial limitations that most smartphone games use to extract money from players. The free-to-play model, which asks you to download a title for free and then put up with annoying ads or time restrictions or pay to remove them, often temporarily, is now as dominant in app stores as a paid game. rarely has a chance of success. It’s a system that actively rewards hostile design for players. It works, in the sense that it makes a lot of money, but it’s also awful.

We’ve all seen the headlines about kids inadvertently spending unbelievable amounts of their parents’ money on these games. But even if you have the right parental controls and your offspring can’t max out their credit card on treats for your virtual panda, these systems still habituate kids to a compulsive form of drip-feeding play that can’t be developmentally healthy. . brains (or any brains, really). This week, I had a conversation with my six-year-old son about removing the ad-adorned free soccer games that had sneaked onto his tablet over the Christmas holidays. “But I LIKE ads!” he complained. I asked him, “Wouldn’t you rather play a game that doesn’t constantly pester you to buy or accumulate virtual money to unlock things? “But the money IS the game!” The point is that he is not wrong.

There are ways to make free play fair and discreet, but many smartphone games are firstly exercises to accumulate money and secondly creative products. Even a good game can be affected by this cutthroat business model. Meanwhile, the games designed around it are often terrible; the worst examples ask you for money every few minutes. When only 5-10% of your game’s audience ever pays, you have to aggressively monetize the players who do. This jargon has gone out of fashion in recent years because it was overtly exploitative, but during the early boom years of smartphone game developers they used to talk about “whales”, the top 0.5% of gamers who would spend many thousands in a single game. . This is the same language the gaming industry uses to describe high rollers.

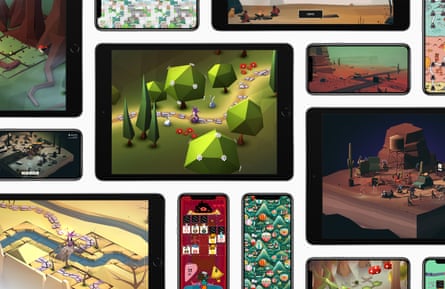

I still think that smartphone games are full of creative potential. Apple Arcade, the iOS subscription service that offers access to a couple hundred “premium” (meaning not full of ads or microtransactions) games, continues to be a showcase for high-quality and weird stuff like Sneaky Sasquatch, Sayonara Wild Hearts and assemble carefully. But the business model has been actively strangling creativity in this space for years, even as it makes more and more money. It has become an example of the best and the worst of how the video game industry works. Every once in a while you have a world-changing moment of genius like Pokémon Go, which brings people together and redefines what gaming can be, but many other hits are actively designed to keep players stuck in a rut, tapping for get a drop of dopamine. .

what to play

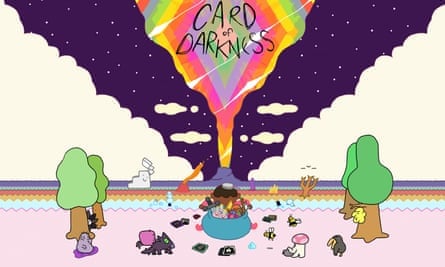

If you want the best of mobile gaming creativity, I can wholeheartedly recommend Apple Arcade if you have an iPhone or iPad – their selection is excellent. In the last few months I have played plow football with my son, who has some lovely retro vibes; card of darkness, a cute and relaxing card game illustrated by Adventure Time creator Pendleton Ward; the mind expanding puzzle game multiple garden; Y really bad chess, which is played with random pieces, so you could end up with three queens, five warring bishops, and a bunch of pawns. Also included are versions of most of the best mobile games from the last five years, if you’re nostalgic for Threes! or cross path.

Available in: Apple iOS

Approximate playing time: as long as you want

what to read

-

An artist named Cat Graffam recreated Goya’s painting Saturn devouring his son using mario paintcontinuing a long tradition of artists copying the work of the masters as a learning exercise, except this time with a SNES mouse.

-

There’s a new UK studio in town: Maverick Games, made up of some of the top talent from Forza Horizon studio Playground Games, VGC reports. His first game will be an open world game, which may or may not remain in the racing genre.

-

HBO’s adaptation of The Last of Us opens on January 15 in the UK on Sky Atlantic, and the reviews are pretty good.

-

CD Projekt Red has paid $1.85 million to resolve a lawsuit with investors claiming to have been misled about the state of Cyberpunk 2077, a game that launched in sorry condition in 2020 but has since saved its reputation.

-

Despite not being available until now due to manufacturing issues, the PlayStation 5 has now sold 30 million units, Sony gaming chief Jim Ryan has said. announced at the CES technology fair.

what to click

Game time is over: How 2023 could reshape video games

“He Gives Us Every Bit Of Himself”: How God of War Actors Hold The Entire Game Together

Super Bomberman Saved My Christmas And My Middle-Aged Video Game Dad Pride: Dominik Diamond

A complete guide to this week’s entertainment.

block of questions

Reader Adam I asked a question that I have wanted to answer for a long time:

“I recently bought a second hand Nintendo 3DS and am catching up on some of the wonderful games that have been released for it. I also really enjoy glasses-free 3D, which got me thinking: What are your favorite Nintendo tricks from the past and what would you like them to do next?

Whenever a game company comes up with a brilliant new idea, that company (and commentators) tend to herald it as the future of gaming. Motion controls? Future of games. The Kinect camera? Future of games. Virtual reality headsets? Turns out, it’s actually not the future of gaming. Most of these things are cool ideas that don’t really revolutionize the way we play the game, but are fun at the time nonetheless. Nintendo takes this attitude with its hardware: it’s just testing things. 3D didn’t work with Virtual Boy, but they did with 3DS. The Wii’s motion control was very popular, but the Wii U’s second screen was not.

My favorite of all was the original. Nintendo DS Dual Screens, and his other little tricks. I loved the wild things the developers did with it: blow into the microphone to put out a fire; fix the console so that the screens mirror each other to solve a puzzle; opening and closing the lid to seal a virtual paperwork. In one of the DS Zelda games, you have to yell at someone across a river to bring down a bridge, which made me crazy thinking about it and then delighted when it actually worked. I’m also one of 11 people who enjoyed playing Super Mario 64 with my thumb on a touch screen. The Switch consolidated Nintendo’s home and handheld consoles, possibly marking the end of these wild hardware experiments, but I’d definitely buy a new dual-screen console. Maybe give it a crank, like the game date.