The secret behind sushi’s high-tech future lies in an unremarkable building on the back streets of Osaka.

Inside, empty plastic cups and plates garnished with crumpled wet paper, to replicate the weight and texture of the scallops, move along a conveyor belt.

Off to the side, hidden behind a plastic screen, technicians monitor data on computer screens, the details of their work considered off-limits to the public. Observer and a small group of journalists were granted exceptional access to the development “studio” belonging to Sushiro, the leading force in Japan’s multi-billion dollar sushi train industry.

This is where developers make incremental improvements to the restaurant chain’s ability to deliver freshly made sushi to diners’ tables at lightning speeds, and stay one step ahead of the competition in an industry whose value is increasing. estimated at 740 billion yen (about £4 billion).

“In the past, diners used to grab whatever they wanted from a free-for-all conveyor belt, but these days most people want to order their favorite sushi,” said Masato Sugihara, deputy manager of the parent company’s IT department. from Sushiro. Food and Life.

The studio replicates a typical Sushiro restaurant. “Here we can make sure the delivery system is working properly and get the right order to the right customer as quickly as possible,” he said. “We can make adjustments, like improving the diner interface with the online menu, that we can’t do in real time in our restaurants.

“It’s not exactly a secret, but our neighbors have no idea what we’re doing here.”

The holy grail of rotating sushi (or kaitenzushi) is flawless, low-budget contactless dining, a trend accelerated by the pandemic and labor shortages that will leave Japan with an estimated shortfall of 6.4 million workers by 2030.

Not far from the secretive hub of Sushiro, staff prepare for lunch at the chain’s Namba district outlet, one of nearly 4,000 kaitenzushi restaurants all over Japan.

Diners in the 236-seat restaurant use a touch panel to choose from 150 items, from sushi and fried chicken to coffee and pastries. Your bill is automatically calculated and payment is made via a machine at the checkout, where customers who have ordered takeout online retrieve their orders from a bank of lockers.

It’s a far cry from the traditional sushi of the popular imagination, where stern-looking artisan chefs with years of training lay out lovingly prepared seafood platters on wooden counters.

But Nobuo Yonekawa, an expert in kaitenzushi, says the industry is losing its appeal amid rising prices and competition from other budget cookers. “The number of customers is declining, and to win them back, the industry needs to think about technology in a different way,” said Yonekawa, who has wrote a book about the topic.

Although high-end establishments are not lacking, the consumption of sushi has undergone a revolution since the first kaitenzushi it opened in Osaka in 1958. Purists may protest, but automation has made it possible to take sushi out of the exclusive and expensive realm of Sukiyabashi Jiro et al and into fast food to compete with burgers and fried chicken.

The massive consumption of sushi has only been possible thanks to the evolution of technology, together with a cultural change of gastronomic exclusivity.

At Sushiro’s Namba Amza restaurant, each dish has a label that allows you to determine in real time which sushi is selling well. The labels are read by sensors below the conveyor belt, ensuring the correct order is delivered to each table. Plates that are not picked up, and those in a second “free for all” belt where diners can help themselves, are automatically removed after traveling 350 meters.

“We use AI to analyze which dishes are popular at particular restaurants and order fish accordingly,” said Yutaka Sakaguchi, IT director at Food and Life. “In the early days of kaitenzushi, the chefs did not have a clear idea of what people wanted. They had to act on instinct.

“It allows us to reduce food waste, but it also allows managers to predict with some confidence what kind of sushi to make and how many staff will be needed on certain days. It also takes the weather into account… for example, which dishes are most popular when it’s hot and sunny. Before we had this system, we had a lot of food waste.”

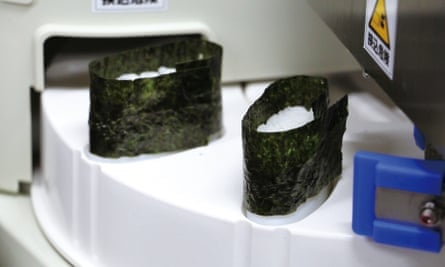

In the back of the kitchen, a robot produces small blocks of rice at a rate of about 3,600 per hour. “It’s impossible for a chef to do it that fast,” said Yurika Murai of Sushiro’s public relations department. Each block is identical and is served, as tradition dictates, at skin temperature.

“The machine is programmed to make the sushi look as if it were formed by human hands,” Murai added. “They’re not just soulless rice blocks.” Further down the production line, another device wraps pieces of rice in nori seaweed for chefs to finish plating and placing on conveyor belts.

The rule is that the sushi must be in front of the customer no more than three minutes after the order has arrived. Yellow and red lights come on to warn chefs that an order hasn’t come out yet.

“Our main challenge is understanding at peak lunch and dinner times which fish is being ordered the most,” Sugihara said. “You can’t just flood the conveyor belt with too many plates, so we count the number of customers and the average number of plates ordered at certain times of the day, and this allows us to anticipate demand during busy and slow periods. activity. ”

But there are certain tasks that are still reserved for humans, such as slicing fish and placing it on top of rice. “Removing the dishes and cleaning the tables is also difficult for the machines,” Sakaguchi said. “But labor shortages are making it harder and harder to find new staff, so we need more automation. Perhaps the answer lies in more robots, but we are not there yet.”

Sushiro president Koichi Mizutome rejected suggestions that high-tech sushi has robbed the dish, which has existed in its recognizable modern form for some 200 years, of its culture and artistry.

“Our world is about automation and achieving the exact same level of service in all of our restaurants, where people can eat sushi at an affordable price,” he said. “The other [world] it’s all about the individual touch of chefs who have gone through years of training. I think those two worlds of sushi can coexist.”