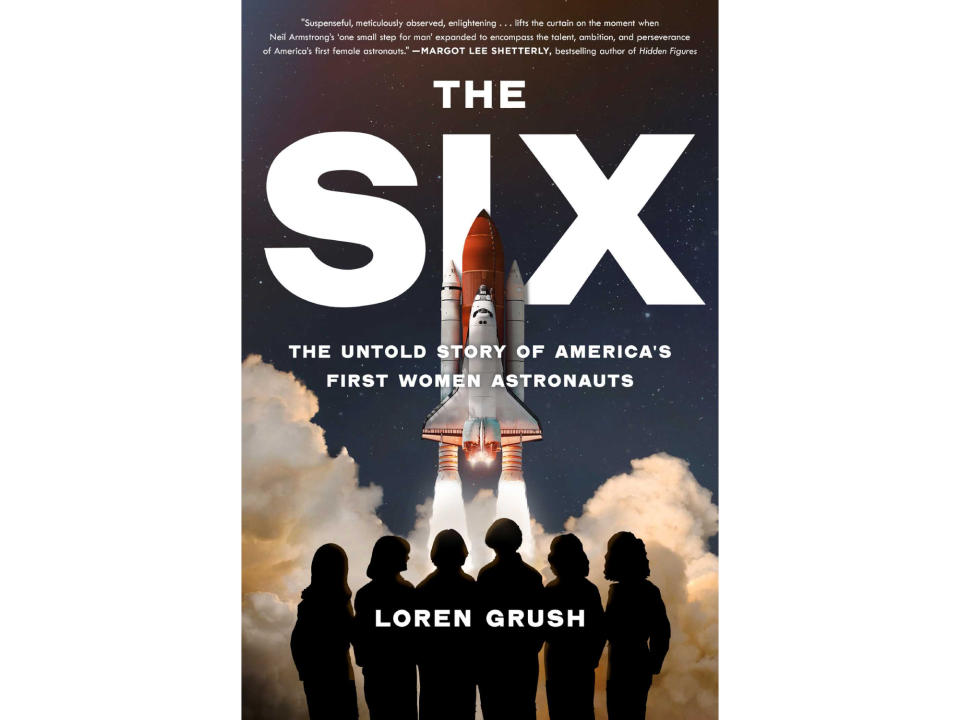

For the first two decades of its existence, NASA was the epitome of an Old Boys Club; its ranks of astronauts came exclusively from the Armed Forces’ test pilot programs which, at the time, were staffed exclusively by men. Glass ceilings weren’t the only thing that was broken when Sally Ride, Judy Resnik, Kathy Sullivan, Anna Fisher, Margaret “Rhea” Seddon and Shannon Lucid were admitted to the program in 1978: numerous spaceflight systems had to be reevaluated to adapt to a more diverse range. staff. In The Six: The Untold Story of America’s First Women Astronauts, Journalist Loren Grush chronicles the many trials and challenges these women faced—from institutional sexism to enduring survival training to coping with the personal pressures of an astronaut’s public life—in their efforts to reach orbit.

Adapted from The Six: The Untold Story of America’s First Women Astronauts by Loren Grush. Copyright © 2023 by Loren Grush. Retrieved with permission from Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Above the Chisos Mountains that stretch across Big Bend National Park in West Texas, Kathy (Sullivan, PhD, third woman to fly in space and future head of NOAA) sat in the back seat of the reconnaissance plane NASA’s WB-57F as it climbed higher into the sky. The pilot, Jim Korkowski, kept his eye on the plane’s altimeter as they climbed. They had just passed sixty thousand feet and had not yet finished ascending. It was a dizzying altitude, but the plane was made to withstand such extremes.

Inside the cabin, both Kathy and Jim were prepared. They were fully equipped with the Air Force’s high-altitude pressure suits. To the untrained observer, the equipment looked almost like real spacesuits. Each outfit consisted of a bulky dark jumpsuit, with thick gloves and a thick helmet. The combination was designed to apply pressure to the body as the high-altitude air dissipated and made it almost impossible for the human body to function.

The duo eventually reached their goal altitude: 63,300 feet. At that altitude, their pressure suits were a matter of life and death. The surrounding air pressure was so low that their blood could begin to boil if their bodies were left unprotected. But with the suits on, it was an uneventful research expedition. Kathy took images with a specialized infrared camera that could produce color photographs and also scanned distant terrain in various wavelengths of light.

They spent only an hour and a half over Big Bend and the flight lasted only four hours in total. While it may have seemed like a quick and easy flight, Kathy made history when she reached that final altitude over West Texas on July 1, 1979. At that time, she flew higher than any woman, setting an unofficial world aviation record. .

The task of training with the WB-57 had scared her at first, but Kathy ended up loving those high-flying planes. “That was a lot of fun, other than that vague little worry that ‘I hope this doesn’t mean I’m falling off the face of the Earth,'” she Kathy said. Her assignment took her on flights north to Alaska and south to Peru. As she expected, she received full qualification to wear the Air Force’s pressure suits, becoming the first woman to do so. Soon, donning a full-body suit designed to keep her alive became second nature to her.

NASA officials had also sought her out to test new equipment they were developing for future Shuttle astronauts, one that would allow people to relieve themselves while in space. During the Apollo and Gemini eras, NASA developed a relatively complex apparatus for astronauts to urinate in their flight suits. It was, essentially, a flexible rubber sleeve that fit around the penis and then connected to a collection bag. The condom-like sleeves came in “small,” “medium,” and “large” sizes (although Michael Collins claimed the astronauts gave them their own terms: “extra-large,” “huge,” and “incredible”). It was certainly not a foolproof system. Urine often leaked out from under the cover.

Handcuffs certainly weren’t going to work once women entered the astronaut corps. While the space shuttle had a fancy new toilet for both men and women to use, the astronauts still needed some outlet for when they were strapped to their seats for hours, waiting for launch or reentry. And if one of the women were to do a spacewalk, she would need some kind of device during those hours afloat. So NASA engineers created the Disposable Absorption Containment Trunk (DACT). In its most basic form it was. . . a diaper It was an easy solution in case the astronauts needed to urinate out of reach of the toilet. It was also designed to absorb fecal matter, although women probably chose to wait until they reached orbit to do so.

Kathy was the best person to try it. Often during her high-altitude flights, she would be trapped in her pressure suit for hours, creating the perfect testing conditions to analyze the DACT’s durability. She worked like a charm. And although the first male Shuttle pilots stayed with handcuffs, over time the DACT became standard equipment for all.

After racking up hundreds of hours in these pressure suits, Kathy hoped to parlay her experience into a flight assignment, one that might allow her to take a ride outside the space shuttle one day. As luck would have it, one afternoon she ran into Bruce McCandless II in the JSC gym. He was the person she needed to know when it came to spacewalks. NASA officials had put him in charge of developing all spacewalk procedures and protocols, and at times he seemed to live in the NASA pools. Plus, she was always recruiting one of Kathy’s classmates to do mock races with him in the tanks. Kathy wanted to be next. Projecting as much confidence as she could, she asked him to consider her for her next training.

It worked. Bruce invited Kathy to accompany him to the Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama to dive in the tank there. The two would be working on spacewalking techniques that could one day be used to assemble a space station. However, the space shuttle suits were not yet ready for use. Kathy had to wear Apollo moonwalker Pete Conrad’s suit, just as Anna had done during her spacewalk simulations. But although the suit swallowed little Anna, it was a little too small for Kathy, about an inch. When she put it on, her suit stabbed into her shoulders, while parts of it seemed to stab into her chest and back. She tried to get up and almost fainted. It took all of her strength to walk towards the pool before falling into the tank. In the simulated weightlessness environment, the pain immediately evaporated. But it was still a crucial lesson in the size of spacesuits. Suits must fit those wearing them perfectly for spacewalking to work.

The session may have started off painfully, but once she started playing with the tools and understanding how to maneuver her arms to move the rest of her body, she was hooked. She loved walking in space so much that she would perform dozens more practice dives during her training.

But practicing in the pool was not enough. She wanted to go to orbit.

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER