Virtually all televisions and Film production uses CG today, but a fully digital program takes it to another level. Seth MacFarlane's “Ted” is one of them, and his production company Fuzzy Door has created a set of augmented reality tools on set called Viewscreen turning this potentially awkward process into an opportunity for collaboration and improvisation.

Working with a computer-generated character or environment is difficult for both actors and crew. Imagine talking to an empty place marker while someone converses off-camera, or pretending that a tennis ball on a stick is a shuttle arriving at the landing bay. Until all production takes place on a holodeck, these CG assets will remain invisible, but Viewscreen at least allows everyone to work with them in-camera, in real time.

“It dramatically improves the creative process and we can get the shots we need much more quickly,” MacFarlane told TechCrunch.

The usual process for filming with CG assets takes place almost entirely after the cameras are turned off. You film the scene with a character stand-in, whether it's a tennis ball or a mocap artist, and give the actors and camera operators marks and framing of how you expect it to play out. You then send your footage to the VFX people, who send you back a draft, which must then be adjusted to taste or remade. It is an iterative process, executed traditionally, that leaves little room for spontaneity and often makes these shots tedious and complex.

“Basically, this came from my need as a visual effects supervisor to show the invisible that everyone is supposed to interact with,” said Brandon Fayette, co-founder of Fuzzy Door. “It is very difficult to film things that have digital elements, because they are not there. It's difficult for the director, the camera operator has trouble framing, the gaffers and lighting people can't get the lighting to work properly on the digital element. Imagine if you could actually see the imaginary things on set, that day.”

Image credits: blurred door

You might say, “I can do that with my iPhone right now. Have you ever heard of ARKit? But although the technology involved is similar (and in fact Viewscreen uses iPhones), the difference is that one is a toy and the other a tool. Sure, you can place a virtual character on a set in your AR app. But the real cameras don't see it; the set monitors don't show it; the voice actor doesn't sync with him; the visual effects team can't base the final shots on that, and so on. It is not about putting a digital character on stage, but about doing so by integrating it with modern production standards.

Viewscreen Studio syncs wirelessly between multiple cameras (real ones, like Sony's Venice line) and can integrate multiple data streams simultaneously through a central 3D positioning and compositing box. They call it ProVis, or production visualization, a middle ground between pre and post.

For a shot of Ted, for example, two cameras can have wide, close shots of the bear, which is being controlled by someone on set with a gamepad or iPhone. MacFarlane performs his voice and gestures live, while a behavioral ai maintains the character's positions and his gaze on the target. Fayette demonstrated this to me live on a small scale, positioning and animating a version of Ted next to him that included live face capture and free motion.

An example of Viewscreen Studio in action, with a live image of the set at the bottom and the final shot at the top. Image credits: blurred door

Meanwhile, the cameras and computer are recording clean images, clean visual effects, and a live composition both in the viewfinder and on monitors that everyone can see, all time-coded and ready for the rest of the production process.

Assets can be given new live instructions or attributes, such as landmarks or lighting. A virtual camera can be moved across the screen, allowing alternate shots and scenarios to occur naturally. A path can only be shown in the viewfinder of a motion camera so that the operator can plan his shot.

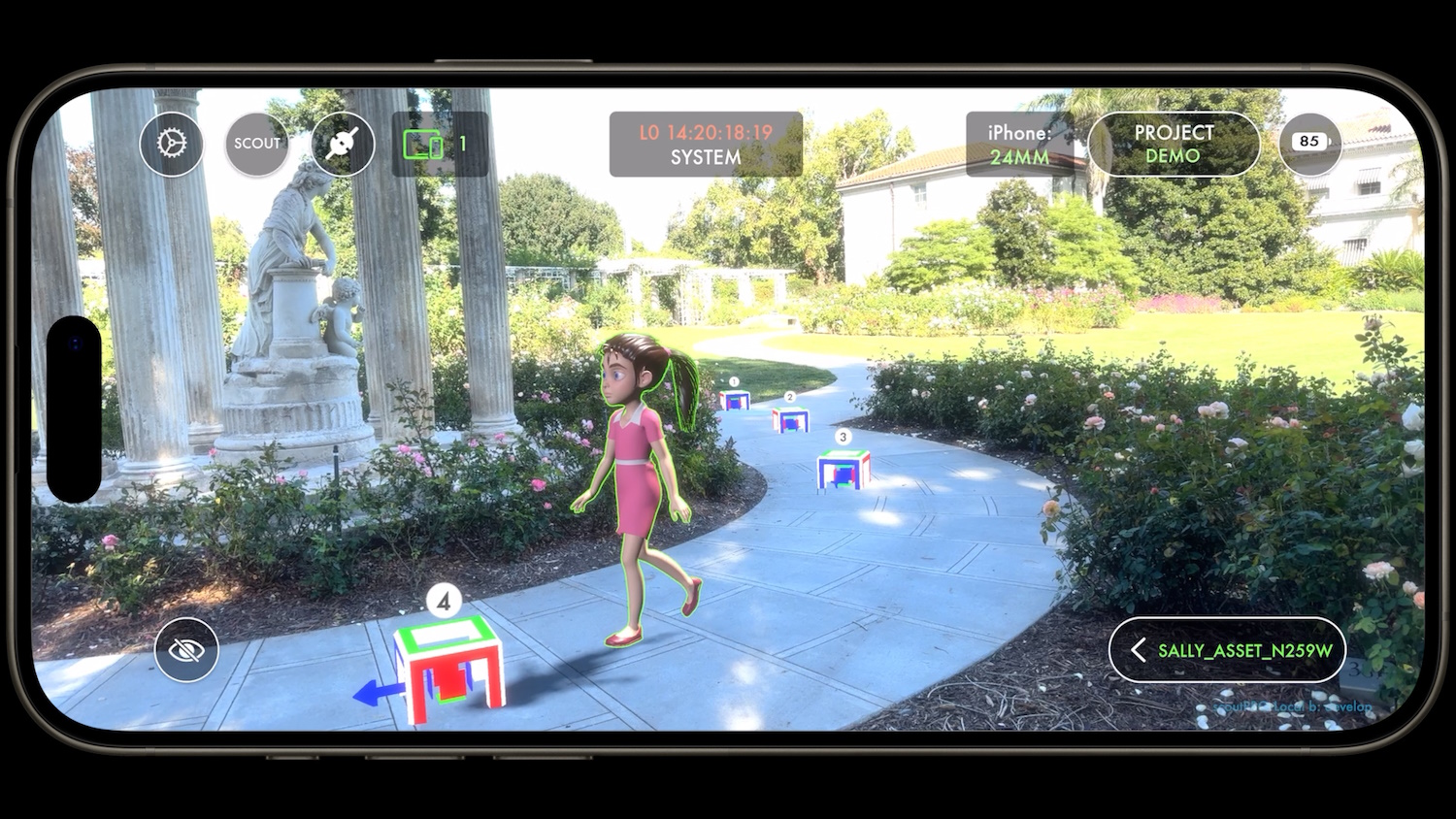

Example resources in a shot with a virtual character: the girl model will walk between the reference points, which correspond to real space.

What if the director decides that Ted the teddy bear should jump off the couch and walk? Or what if they want to try more dynamic camera movement to highlight an alien landscape in The Orville? That's simply not something you can do in the pre-baked process typically used for this product.

Of course, virtual productions in LED cabinets address some of these issues, but you run into the same things. You get creative freedom with dynamic backgrounds and lighting, but much of a scene actually has to be well defined due to the limitations of how these giant sets work.

“Just doing a setup for a shuttle landing on The Orville would require about seven takes and take 15 to 20 minutes. Now we have them in two takes and it's three minutes,” Fayette said. “Not only do we find ourselves with shorter days, but we also try new things: we get to play a little. It helps eliminate the technical and allows creativity to take control…the technique will always be there, but when you let the creatives create, the quality of the shots becomes much more advanced and fun. And it makes people feel that the characters are real: we are not staring into space.”

It's not just theoretical, either: he said they filmed Ted this way, “the entire production, for about 3,000 takes.” Traditional VFX artists eventually take over the final quality effects, but they aren't tapped every few hours to render some new variant that could go straight into the trash.

If you're in business, you might want to learn about the four Studio product-specific modules, right from Fuzzy Door:

- Tracker (iOS): Tracker that transmits asset position data from an iPhone mounted on a cinematographer's camera and sends it to Composer.

- Compositor (Windows/macOS): Compositor is a macOS/WIN application that combines the video stream from a film camera and position data from Tracker to compose VFX/CG elements into a video.

- Exporter (Windows/macOS): The exporter collects and compiles frames, metadata, and all other Compositor data to deliver standard camera files at the end of the day.

- Motion (iOS): Stream facial animation and body movements from a live actor, on set, to a digital character using an iPhone. The movement has no marker or suit: no fancy equipment required.

Viewscreen also has a mobile app, Scout, to do something similar on-site. This is closer to your average AR app, but again includes the kind of metadata and tools you'd want if you were planning a photo shoot.

Image credits: blurred door

“When we were exploring The Orville, we used ViewScreen Scout to visualize what a spaceship or character would look like on location. Our visual effects supervisor would text me the shots and I would immediately give him feedback. In the past, this could have taken weeks,” MacFarlane said.

Bringing in official resources and encouraging them while an exploration is being conducted greatly reduces time and costs, Fayette said. “The director, the photographer (the assistant directors) can all see the same thing, we can import and change things live. For The Orville we had to put this creature moving in the background, and we were able to take the animation directly to Scout and say, 'Okay, that's too fast, maybe we need a crane.' “It allows us to find answers to exploration problems very quickly.”

Fuzzy Door officially offers its tools today, but has already worked with some studios and productions. “The way we sell them is personalized,” explained Faith Sedline, the company's president. “Each show has different needs, so we partner with studios and read their scripts. Sometimes they care more about the set than the characters, but if it's digital, we can do it.”