Extreme weather events are on the rise around the world, from historic floods to unseasonable heat waves and devastating wildfires.

You don't have to look far to find fuel for climate-related fear and fear. anxiety.

Heidi Rose, an elementary school teacher in Denver, Colorado, knows this all too well. She experienced years of what she describes as “pretty intense” climate anxiety, which began around 2015, as she watched natural disasters unfold on the news and close up.

“I was having a hard time functioning and kept thinking about how far we are from the point of no return,” she says, sitting on a too-small stool at a shared table in her first-grade classroom at Lincoln Elementary School.

His dismay seeped into his work, he acknowledges. Back then, he talked to his students about climate and sustainability, as he has long done, but he focused too much on what doesn't work, like how much trash is floating in the instagram.com/p/BYwfPoXFzE-/” target=”_blank” rel=”noopener nofollow”>ocean.

These days, Rose has shifted her focus, partly because she herself has developed a healthier perspective on climate change, but also because she sees that there are more effective ways to introduce young people to climate education and sustainability practices, especially to early students like her. first grade students.

“One thing that I think is really important when you talk to younger children, especially about this topic, is to try to do it in a way that focuses on appreciation and love, and less on fear and doom and sadness. “Rose says. “I don't want the first conversations you have about (climate) to focus too much on the problems or how bad things are.”

Rose is among a growing number of classroom teachers who, either of their own volition or by directives of their states, are introducing students to climate change and the forces behind it. In most cases, teachers avoid talking about the topic in a way that incites fear or makes the topic seem abstract to children.

Instead, educators emphasize the importance of infusing hope into these classroom conversations. They also share that they are grounding these lessons in local realities and focusing on sustainability in their own communities, while emphasizing the interconnectedness of people and places around the world.

Moving away from abstraction

Climate change is generally too broad a topic to address with younger children (think preschoolers, kindergarteners, and first graders), says Mark Windschitl, a professor of science education at the University of Washington and author of Teaching Climate Change: Fostering Understanding, Resilience, and Commitment to Justice.

“It's too abstract,” he says. “It's bleak.”

But teachers can still play a key role in helping young students develop the skills needed to think critically about this topic in the future. And they can help develop fundamental knowledge.

Windschitl, a former science teacher, says sustainability is a good starting point, especially if it is taught in a concrete way that children can understand.

Telling kids to throw their banana peels in a compost bin because it helps the planet, he says, isn't as effective. But explaining to them the process that begins after the compost bin is collected and relating it to their role in it can be.

In her first-grade classroom, Rose has a waste sorting station that she introduces to her students at the beginning of the school year. She explains to them what a landfill is, explains what happens there, and shows them videos so they can see what a landfill is like. She does the same with compostables and the three different types of recycling bins in her classroom. (Rose has a personal subscription to Ridwella service that allows you to get rid of students' hard-to-recycle trash).

The goal of the waste sorting station, she says, is to get the 6- and 7-year-olds in her class to think independently when they throw something away: Should this go in the trash, a recycling bin, or the compost bin… and why? It's also to help you connect the dots about waste. “It's not like we just put the plastic in a container and it's gone,” Rose says. “It's going somewhere.”

“I try to plant the seed, but without tying it to anything heavy or creating feelings of shame or guilt,” Rose adds, noting that many kids' snacks come in plastic containers, and that's okay. “It's more of a sense of intentionality and connecting what we use with its origin. Simply awareness and connection with the planet.”

Lessons based on local examples

Another way teachers are making climate and sustainability more relevant to children is by basing lessons on local examples. The global scale of climate change is enormous. It's easier for kids if they can first understand how this affects people in their neighborhood, many educators say.

“We know that climate change is very complex, very overwhelming, very difficult to understand,” says Manuela Zamora, executive director of New York Sun Worksa nonprofit organization that has helped open hydroponic classrooms in more than 300 public schools in New York City and New Jersey, where it also promotes science education on climate change and sustainability.

“We always come back to asking why and how is this relevant to me, then how is this relevant to my community, then to my city, then to my planet,” he says of the group's climate change curriculum.

Local and community examples help students dispel the notion that climate change is a remote concern that only affects polar bears, Zamora adds.

“Children are very present in the day they are in, in the place they are in,” says Elaine Makarevich, who taught elementary school for 30 years before recently becoming New Jersey's state leader for Subject to weathera hub that connects educators with standards-aligned resources for teaching about climate change.

In rural areas, like the one where Makarevich taught, public transportation is inaccessible. And it makes no sense, he says, to encourage children to walk or ride a bike when it might take their families a 20-minute drive to get to the nearest supermarket.

“It's different in different places,” he adds. “If you are in a community with flooded homes, the concern is different. “It’s very place-based.”

Once children understand their local challenges, educators say, they can begin to connect the needs of their own community with the needs and experiences of communities around the world.

Leading with hope

Even when teaching children as young as kindergarten, Makarevich tried to instill in his students a love for the planet, an appreciation for how interconnected its inhabitants are, and care and concern for its future.

As students get older, those conversations become “deeper and richer,” he says. They can learn not only to respect the planet but to understand “how it works, what it gives us and what we give it.”

In every lesson, even those about climate change, “there was always that foundation of hopeful solutions,” Makarevich shares. “That's really important.”

Five-year-olds can help recycle in their classroom and cafeteria. They can plant flowers, she says. Ten-year-olds can participate in community cleanups or join the school's “green team,” if it has one.

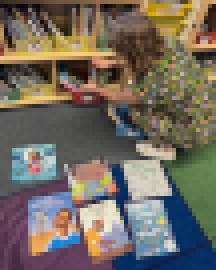

In Rose's classroom in Denver, she has two bins full of children's books about conservation and the planet. This helps her talk about the Earth in an “optimistic and honest” way, she says.

It's still far from perfect. Every day, he admits, 260 plastic utensils are used at his primary school.

“We're a little limited in the big changes we can make as a school, maybe even as a district,” Rose says. “I focus more on what is within my control as a teacher instead of getting lost in what is out of my control.”

It's not very different, he says, from what he tries to communicate to his students. They may not be able to control the main drivers of climate change, even when they are older, but they can develop an awareness and connection to the planet. And that's a start.

<script async src="//www.instagram.com/embed.js”>