Welcome to the latest installment in our series on 21st-century education. Throughout this series, we have delved into the characteristics of 21st-century teachers, students, classrooms, and the very nature of learning itself. As an educational researcher deeply interested in the intersection of technology and education, I have been keenly observing how emerging technologies have been reshaping the landscape of learning. These technologies, I believe, are creating new learning habits and spaces, transforming how education is delivered and consumed.

In this ever-evolving educational paradigm, the role of learners has become more complex and demanding. With technologies like ai taking the world by surprise, the ability to generate and access knowledge has become almost ubiquitous for anyone with an internet connection. This democratization of knowledge brings with it a greater responsibility for learners. They need to be equipped with a robust set of skills to navigate this new landscape effectively. Critical thinking becomes imperative in an age where information is plentiful and continuously evolving.

Today, we turn our focus to the characteristics of 21st-century learners. In a world where ai and digital technologies are prevalent, understanding what defines a learner in this new era is crucial. These learners are not just passive recipients of information; they are active participants in their educational journeys, equipped to handle the challenges and opportunities that come with a technology-driven world. Let’s explore these characteristics and understand why they are essential for success and adaptability in the 21st century.

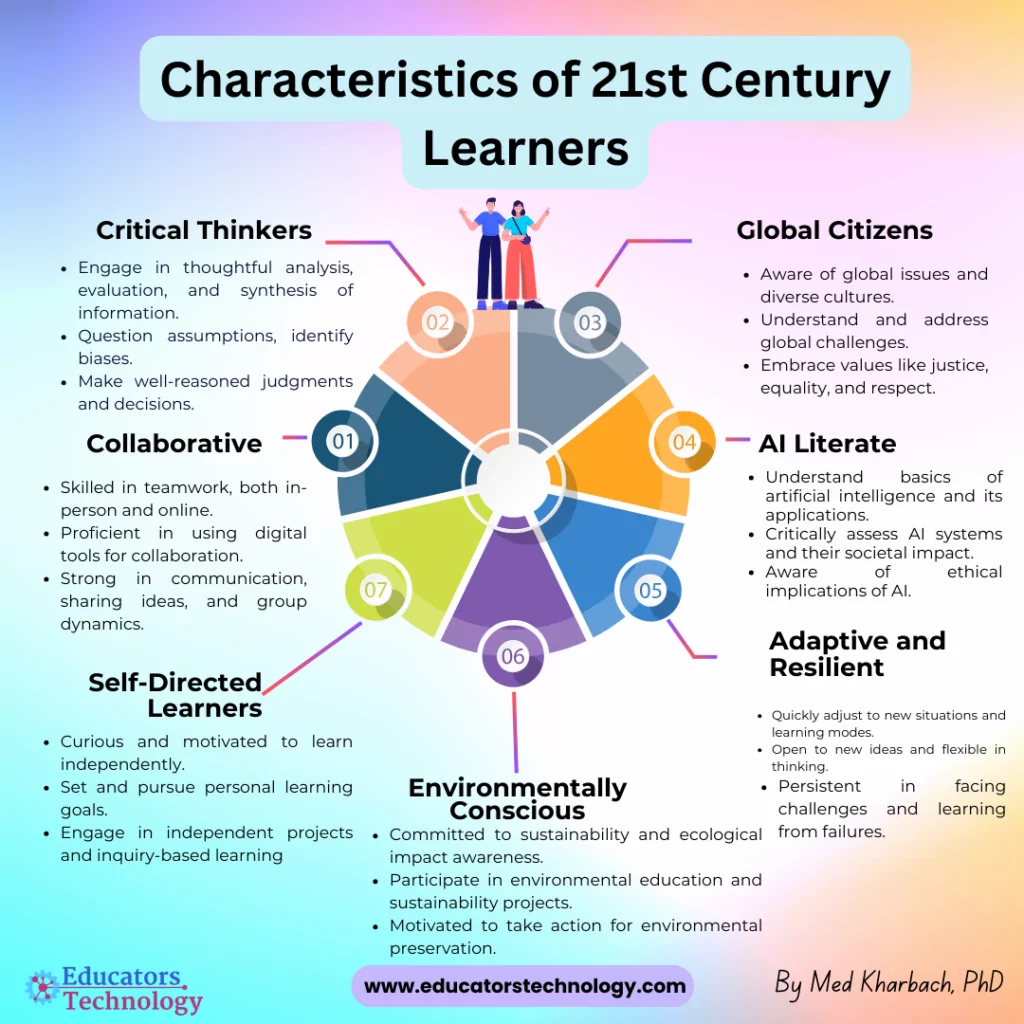

Characteristics of 21st Century Learners

Here are some of what I believe are key characteristics of 21st century learners. I tried to categorize them into these main headings:

1. Collaborative

Collaboration is a key skill for 21st-century learners, reflecting the interconnected and cooperative nature of the modern world. This skill involves the ability to work effectively in teams, both in-person and virtually. Collaborative learners are adept at communicating, sharing ideas, and pooling resources to achieve common goals. They understand how to navigate group dynamics, allocate tasks based on individual strengths, and reach consensus while valuing diverse perspectives.

In the digital age, this also means being proficient in using online tools for collaboration, such as cloud-based document sharing, video conferencing, and collaborative project management software. I believe that fostering collaborative skills in students not only prepares them for the teamwork required in most professional environments but also enhances their social and emotional learning. It teaches them empathy, listening, and negotiation skills, which are invaluable in both personal and professional contexts.

2. Creative and Innovative

Creativity and innovation are at the heart of 21st-century learning (Kettler et al, 2019). This involves thinking outside traditional frameworks, being open to new ideas, and approaching problems in novel ways. Creative and innovative learners are not just skilled in artistic or imaginative endeavors but also in applying these traits to problem-solving and academic tasks.

Such learners are often willing to take risks, embrace new methodologies, and experiment with different solutions. They see challenges as opportunities for innovation and are not deterred by failure, often using it as a stepping stone to success. Besides developing critical thinking skills, encouraging creativity and innovation in students also fosters a sense of curiosity and a lifelong love for learning. These traits are particularly important in a world where traditional solutions may not address the complexities of modern challenges.

3. Critical Thinkers

Critical thinking is a concept that is not easy to pin down and different scholars define it differently, each focusing on specific aspects. For instance, psychologist Robert Sternberg (1985) defines critical thinking as “the mental processes, strategies, and representations people use to solve problems, make decisions, and learn new concepts” (cited in Shaw, 2014, p. 66). This definition highlights critical thinking as a broad set of cognitive skills used in problem-solving and learning.

On their part, in a paper presented at the 8th Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking, Michael Scriven and Richard Paul (1987) define critical thinking as

The intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. In its exemplary form, it is based on universal intellectual values that transcend subject matter divisions: clarity, accuracy, precision, consistency, relevance, sound evidence, good reasons, depth, breadth, and fairness.

This definition emphasizes the disciplined and active nature of critical thinking, involving a range of cognitive activities to guide belief and action.

In How Critical Is Critical Thinking?, Ryan D. Shaw (2014) explores the concept of critical thinking in the context of music education. Shaw discusses how critical thinking, traditionally seen as a skill for problem-solving and music listening, can be deepened by integrating concepts from Critical Theory and pedagogy. Shaw suggests that critical thinking should not just be about problem-solving but also about empowering students to pursue change and take critical action, moving beyond passive learning to active engagement and reflection.

A common thread among all these definitions is that they underscore the active, disciplined, and multifaceted nature of critical thinking, framing it as a key skill for learners in navigating complex problems and forming well-reasoned beliefs and actions. This aligns well with the idea of 21st-century learners as critical thinkers, capable of engaging deeply with information and challenges.

By engaging deeply I mean being able to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information in a thoughtful and discerning manner. It means looking at problems from different angels and using various perspectives, questioning assumptions, and identifying biases.

4. Global Citizens

Global citizenship in 21st-century learners is characterized by an awareness and understanding of global issues, cultures, and perspectives. In the book Global Citizenship Education (GCE), UNESCO views GCE as an education that embodies a radical paradigm shift, focusing on developing learners’ knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes essential for a world that is more just, peaceful, tolerant, inclusive, secure, and sustainable.

This concept extends beyond traditional education, emphasizing the understanding and resolution of global issues across social, political, cultural, economic, and environmental dimensions. As the UNESCO states, GCE fosters a multifaceted approach, integrating methodologies from various fields like human rights education, peace education, and sustainable development.

Additionally, the book highlights the critical role of GCE in equipping learners with competencies to navigate the dynamic and interconnected world of the 21st century. I find these competencies interesting and worth sharing here. They involve fostering:

- An understanding of multiple identity levels and the potential for a ‘collective identity’ transcending cultural, religious, ethnic, or other differences.

- Deep knowledge of global issues and universal values such as justice, equality, dignity, and respect.

- Cognitive skills for critical, systemic, and creative thinking, including a multi-perspective approach to issues.

- Non-cognitive skills, including empathy, conflict resolution, effective communication, and the ability to interact with diverse groups.

- Behavioral capacities for collaborative and responsible action to address global challenges and strive for collective good.

In essence, being a global citizen in the 21st century, as per the UNESCO framework, means being educated and empowered to actively contribute to a more equitable, peaceful, and sustainable world. This trait reflects an acknowledgment of interconnectedness in a globalized world. Learners who are global citizens are curious about the world beyond their immediate environment.

They understand the importance of cultural sensitivity and appreciate diversity. In educational settings, this can manifest through learning about global histories, economies, and societies. It also involves discussing international issues like climate change, global health, or international relations.

5. Digitally Proficient

In the digital age, proficiency with technology is a fundamental aspect of being a 21st-century learner. This entails more than basic computer skills; it involves a comprehensive understanding of various digital tools and platforms and the ability to navigate online environments effectively.

Digital proficiency or digital literacy (the terms are often used interchangeably, Spante et al, 2018) includes using the internet for research, leveraging educational apps and software for learning, and understanding how to communicate and collaborate in virtual spaces. This digital fluency also extends to critical skills such as discerning credible sources of information online, understanding the principles of digital etiquette, and managing digital footprints.

In my experience, digitally proficient students are better equipped to access a vast range of learning resources and collaborate on a global scale. They are adept at using technology not just as a tool, but as an integral part of their learning process, preparing them for a world where digital literacy is increasingly crucial.

6. ai Literacy

ai literacy is an emerging yet vital characteristic of 21st-century learners. It involves understanding the basics of artificial intelligence and its applications in various fields. This means being aware of how ai systems work, how they can be used in learning and everyday life, and recognizing their growing impact on society (see Klein, 2023).

For students, ai literacy is not just about using ai-powered tools but also about developing a critical perspective on how these technologies influence the world. ai literate students can critically assess the information provided by ai systems, understand the limitations of ai, and envision innovative uses of ai in solving real-world problems.

ai literacy also encompasses an understanding of the ethical implications of ai, including privacy concerns and the potential biases in ai systems. If you want to learn more about how technology is deeply implicated in the production and reproduction of racial and other types of prejudices, check out Ruha Benjamin’s book technology intertwines with racial issues, challenging our understanding of neutrality in the digital age.” target=”_blank”>Race after technology as well as this collection of books covering the intricate relation between technology/” target=”_blank” rel=”noopener”>race and technology.

7. Adaptive and Resilient

Adaptability and resilience are key traits for learners in the 21st century, a time characterized by rapid change and uncertainty. As for adaptability, Ployhart and Bliese (2996) define it as “an individual’s ability, skill, disposition, willingness, and/or motivation to change or fit different task, social, or environmental features”. In other words, being adaptive means having the ability to quickly adjust to new situations, environments, or modes of learning. This includes being open to new ideas, flexible in thinking, and willing to step outside one’s comfort zone.

Resilience goes hand in hand with adaptability. According to the American Psychological Association, resilience “is the process and outcome of successfully adapting to difficult or challenging life experiences, especially through mental, emotional, and behavioral flexibility and adjustment to external and internal demands.”

In the context of learning, this means not being deterred by failure but seeing it as a part of the learning process. Resilient students are persistent, able to cope with challenges, and continue striving towards their goals despite obstacles. My experience has shown that fostering adaptability and resilience in students is crucial for their long-term success, as these skills enable them to navigate the complexities of modern life and an ever-evolving future.

8. Environmentally Conscious

Being environmentally conscious is increasingly recognized as a critical aspect of being a 21st-century learner. This involves a commitment to sustainability and an understanding of one’s ecological impact.

Eco-consciousness or environmental consciousness refers to “psychological factors that determine individuals’ propensity towards pro-environmental behaviours”( Mishal et al., 2017, p. 684; see also Zelezny and Schulz, 2000). Kim and Lee (2023) define environmental consciousness as “the willingness to become aware of environmental problems, to support efforts to solve environmental problems, and to personally commit and act to solve these problems” (p. 4)

Incorporating environmental consciousness in education is critical, not just for theoretical understanding, but for shaping the attitudes and behaviors of students towards the environment. Several studies (e.g., Kim & Lee, 2023, Mishal et al., 2017; Zelezny & Schulz, 2000) highlight how environmental awareness influences learners attitudes and behaviors. This connection underscores the necessity of embedding environmental consciousness into the curriculum, as it can lead to more environmentally responsible behaviors in students.

The insights from these studies are particularly valuable for educators and parents. By instilling a sense of environmental responsibility in students, we can foster a generation that not only understands environmental issues but also takes active steps in their daily lives, such as making environmentally friendly purchasing decisions, to mitigate these challenges.

Environmentally conscious learners are aware of environmental issues like climate change, resource depletion, and pollution. They understand the importance of sustainable living and are motivated to take actions that contribute to environmental preservation.

In the classroom, this can include learning about renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, or conservation efforts. Many schools incorporate environmental education into their curricula, encouraging students to participate in sustainability projects or initiatives. As a teacher, promoting environmental consciousness is not just about imparting knowledge; it’s about instilling a mindset that values and works towards a sustainable future.

9. Self-Directed Learners

Self-directed learning is a key characteristic of modern learners. This trait is about taking initiative in one’s learning journey and seeking knowledge beyond the traditional classroom setting. Self-directed learners are characterized by their curiosity, motivation, and ability to set and pursue their learning goals.

According to Knowles (1975), self directed learning

describes a process in which individuals take the initiative, with or without the help of others, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating learning goals, identifying resources for learning, choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies, and evaluating learning outcomes

In an educational context, fostering self-directed learning can involve providing students with opportunities to explore topics of interest, encouraging independent projects, or using inquiry-based learning approaches. From my experience, self-directed learners tend to develop strong problem-solving skills and are well-prepared for lifelong learning, which is essential in our rapidly changing world.

10. Ethically Aware

Ethical awareness, particularly in digital contexts, is increasingly important for 21st-century learners. This involves understanding the ethical implications of actions, especially when using digital tools and platforms.

Ethically aware learners understand issues like digital citizenship, data privacy, and the responsible use of technology. They are aware of the consequences of their actions in digital spaces, including social media, and understand the importance of maintaining a positive digital footprint.

In the classroom, this can be nurtured through discussions on digital ethics, responsible online behavior, and critical thinking about the information consumed and shared online. Teaching students to be ethically aware helps them navigate the digital world responsibly and make informed decisions about their actions.

Final thoughts

To conclude, let me reiterate that that while digitality is taking over, the role of learners in this new era has expanded significantly. 21st century Learners are no longer just recipients of knowledge; they are creators, collaborators, and critical thinkers navigating a rich and complex digital world.

The characteristics we’ve discussed, from digital proficiency and ai literacy to adaptability, creativity, and ethical awareness, are not merely desirable traits. They are essential skills that equip learners to thrive in an environment where knowledge is abundant and constantly evolving. As an educational researcher, I have observed that these skills are crucial for learners to manage the vast amounts of information available, to engage with global issues, and to contribute meaningfully in various contexts.

Sources

- Kettler, T., Lamb, K. N., & Mullet, D. R. (2019). Developing Creativity in the Classroom: Learning and Innovation for 21st-Century Schools. Prufrock Presss.

- Kharbach, M. (2023). What Is Self-directed Kearning. Selected Reads. https://www.selectedreads.com/what-is-self-directed-learning/

- Klein, A. (2023). ai Literacy, Explained. MIT Open Learning, ai-literacy-explained” target=”_blank” rel=”noreferrer noopener”>https://openlearning.mit.edu/news/ai-literacy-explained

- Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Chicago, IL: Follett

- Kim N, Lee K. (2023). Environmental Consciousness, Purchase Intention, and Actual Purchase Behavior of Eco-Friendly Products: The Moderating Impact of Situational Context. Int J Environ Res Public Health.29;20(7):5312. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20075312. PMID: 37047928; PMCID: PMC10093960.

- Lai, E., DiCerbo, K., & Foltz, P. (2017). Skills for Today: What We Know about Teaching and Assessing Collaboration. Pearson.

https://www.pearson.com/content/dam/one-dot-com/one-dot-com/global/Files/efficacy-and-research/skills-for-today/Collaboration-FullReport.pdf - Lin Y.C.,& Chang C.A. (2012). Double Standard : The Role of Green Product Usage. J. Mark. 76 (125–134). doi: 10.1509/jm.11.0264.

- Ployhart R. E., Bliese P. D. (2006). Individual adaptability (I-ADAPT) theory: conceptualizing the antecedents, consequences, and measurement of individual differences in adaptability, in Understanding Adaptability: A Prerequisite for Effective Performance Within Complex Environments, Vol. 6, eds Burke C. S., Pierce L. G., Salas E. (St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Science; ), 3–39

- Robert Sternberg, “Critical Thinking, Its Nature, Measurement, and Improvement,” in Essays on the Intellect, ed. Frances R. Link (Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 1985), 4

- Michael Scriven and Richard Paul, “Defining Critical Thinking,” 2008, accessed October 1, 2013, https://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/766

- Mishal A., Dubey R., Gupta O.K., Luo Z. (2017). Dynamics of environmental consciousness and green purchase behavior: An empirical study. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag.9(682–706). doi: 10.1108/IJCCSM-11-2016-0168.

- Maria Spante, Sylvana Sofkova Hashemi, Mona Lundin & Anne Algers | Shuyan Wang (Reviewing editor). (2018). Digital competence and digital literacy in higher education research: Systematic review of concept use, Cogent Education, 5:1, DOI: 10.1080/2331186X.2018.1519143

- UNESCO. (2014). Global citizenship education: preparing learners for the challenges of the 21st century. Available at https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000227729.locale=en

- Zelezny, L.C. and Schultz, P. (2000), “Psychology of promoting environmentalism: promoting environmentalism”, Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 56 No. 3, pp. 365-371.