In game theory, how can players get to an end if there could still be a better option to decide? Maybe a player still wants to change his decision. But if they do, maybe the other player also wants to change. How can they expect to escape this vicious circle? To solve this problem, the concept of a Nash balance, which I will explain in this article, is essential for games theory.

This article is the second part of a series of four chapters on games theory. If you have not yet reviewed the first chapter, I encourage you to do it to familiarize yourself with the main terms and concepts of games theory. If you did, you are prepared for the next steps of our trip through game theory. Come on!

Find the solution

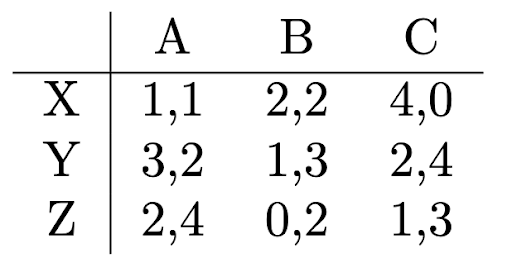

Now we will try to find a solution for a game in game theory. TO solution It is a set of actions, where each player Maximize its usefulness and therefore behaves rationally. That does not necessarily mean that each player wins the game, but does the best they can do, since they do not know what the other players will do. Consider the following game:

If you are not familiar with this matrix note, you may want to take a look at Chapter 1 and update your memory. Do you remember that this matrix gives you the reward for each player given a specific pair of actions? For example, if player 1 chooses the action and and player 2 choose action B, player 1 will obtain a reward of 1 and player 2 will obtain a reward of 3.

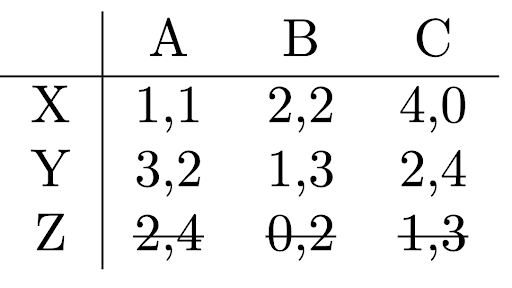

Well, what actions should players decide for now? Player 1 does not know what player 2 will do, but they can still try to find out what the best action would be depending on the election of the player 2. If we compare the utilities of the shares and Z (indicated by the blue and red paintings in the following figure), we notice something interesting: if player 2 chooses action A (first column of the matrix), player 1 will obtain a reward of 3, if they choose the action of 2, if you choose the z action, so the action is better in that case. But what happens, if player 2 decides action B (second column)? In that case, the action and gives a reward of 1 and the action z gives a reward of 0, so and it is better than Z again. And if player 2 chooses Action C (third column), and is even better than Z (2 vs. reward of 1). That means that this player 1 should never use the Z action, because the action is always better.

We compare the rewards for player 1 for shares and and Z.

With the aforementioned considerations, player 2 can anticipate that player 1 would never use the Z action and, therefore, player 2 does not have to worry about the rewards that belong to Action Z. This makes the game much smaller, because now there are only two options for player 1, and this also helps the player 2 to decide for his action.

We discovered that for player 1 and is always better than Z, so we no longer consider Z.

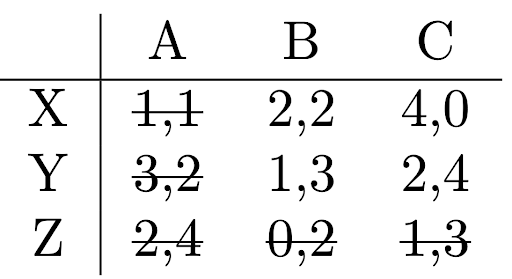

If we observe the truncated game, we see that for player 2, option B is always better than action A. If player 1 chooses x, action B (with a reward of 2) is better than option A (with a reward of 1), and the same applies if player 1 chooses Action Y. Note that this would not be the case if the Z action was still in the game. However, we already saw that the Z action will never be played by player 1 anyway.

We compare the rewards for player 2 for actions A and B.

As a consequence, player 2 would never use action A. Now if player 1 anticipates that player 2 never uses action A, the game becomes smaller again and less options should be considered.

We saw that for player 2 action B is always better than action A, so we no longer have to consider A.

We can easily continue in a way equally and see that for player 1, x is now better than y (2> 1 and 4> 2). Finally, if player 1 chooses action A, player 2 will choose action B, which is better than C (2> 0). In the end, there are only action x (for player 1) and B (for player 2). That is the solution of our game:

In the end, there is only one option, namely player 1 and player 2 using B.

It would be rational for player 1 to choose action x and for player 2 to choose action B. Note that we reach that conclusion without exactly knowledge What the other player would do. We simply anticipate that some actions would never be taken, because they are always worse than other actions. Such actions are called strictly dominated. For example, Action Z is strictly dominated by action and, because and is always better than Z.

The best answer

Such strictly dominated actions do not always exist, but there is a similar concept that is important for us and is called The best answer. Let's say we know what action the other player chooses. In that case, deciding on an action becomes very easy: we only take the action that has the greatest reward. If player 1 knew that player 2 chose option A, the best answer for player 1 would be and, because and has the greatest reward in that column. Do you see how we always look for the best answers before? For each possible action of the other player we look for the best answer, if the other player chose that action. More formally, the best response of the player I to a given set of actions of all other players is the action of player 1 that maximizes the utility given the actions of the other players. Also keep in mind that strictly dominated action can never be a better response.

Let's go back to a game that we present in the first chapter: the dilemma of the prisoners. What are the best answers here?

How should player 1 should decide, if player 2 confesses or denies? If player 2 confesses, player 1 should also confess, because a reward of -3 is better than a reward of -6. And what happens if player 2 denies? In that case, confessing is better again, because it would give a reward of 0, which is better than a reward of -1 to deny. That means that for the player 1 confess is the best answer for both actions of player 2. The player 1 does not have to worry about the actions of the other player, but he must always confess. Due to the symmetry of the game, the same applies to player 2. For them, confess is also the best answer, regardless of what the player 1 does.

Nash's balance

If all players play their best answer, we have reached a solution of the game called Nash balance. This is a key concept in game theory, due to an important property: in a Nash balance, no player has any reason to change his action, Unless any other player does. That means that all players are as happy as they can be in the situation and would not change, even if they could. Consider the prisoner's dilemma from above: Nash's balance is reached when both confess. In this case, no player would change his action without the other. They could improve yes both They changed their action and decided to deny, but since they cannot communicate, they do not expect any change from the other player and, therefore, they are not changed either.

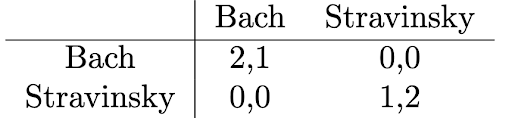

You may wonder if there is always a single Nash balance for each game. Let me tell you that there can also be multiple, as in the Bach vs. game. Stravinsky we already met in chapter 1:

This game has two Nash balances: (Bach, Bach) and (Stravinsky, Stravinsky). In both scenarios, you can easily imagine that there is no reason for any player to change their action in isolation. If you sit at the Bach concert with your friend, you will not leave your seat to go to the Stravinsky concert, even if you favor Stravinsky about Bach. Similarly, Bach's fan would not leave Stravinsky's concert if that meant leaving his friend alone. However, in the remaining two stages, you would think differently: if you were alone at the Stravinsky concert, you will want to go out and join your friend at the Bach concert. That is, you would change your action even if the other player does not change his. This tells you that the scenario you have been was No A Nash balance.

However, there may also be games that have no Nash balance at all. Imagine that you are a football goalkeeper during a penalty shot. To simplify, we assume that you can jump to the left or to the right. The football player of the opposite team can also shoot in the left or right corner, and we assume that you catch the ball if you decide for the same corner as they and do not catch it if you decide for the opposite corners. We can show this game as follows:

You will not find any Nash balance here. Each scenario has a clear winner (reward 1) and a clear loser (reward -1), and therefore, one of the players will always want to change. If you jump to the right and catch the ball, your opponent will want to change to the left corner. But then, he will want to change his decision again, which will make his opponent choose the other corner again, etc.

Summary

This chapter showed how to find solutions for games using the concept of a Nash balance. Let's summarize what we have learned so far:

- A solution of a game in the game theory maximizes the usefulness or reward of each player.

- Is called an action strictly dominated If there is another action that is always better. In this case, it would be irrational to play strictly dominated action.

- The action that produces the greatest reward given the actions taken by the other players is called Best answer.

- TO Nash balance It is a state in which each player plays his best answer.

- In a Nash balance, no player wants to change his action unless any other play does it. In that sense, Nash balances are optimal states.

- Some games have multiple Nash balances and some games have none.

If the fact that there is no Nash balance in some games, don't despair! In the next chapter, we will introduce probabilities of actions and this will allow us to find more balances. Stay tuned!

References

The themes introduced here are generally covered in standard textbooks on games theory. However, I used this, which is written in German:

- Bartholomae, F. and Wiens, M. (2016). Game theory. A text -oriented textbook. Wiesbaden: Springer Specialist Media Wiesbaden.

An alternative in English could be this:

- Espinola-Arredondo, A., & Muñoz-Garcia, F. (2023). Game theory: an introduction with step by step examples. Springer nature.

The play theory is a fairly young field of research, with the first main textbook:

- Von Neumann, J. and Morgenstern, O. (1944). Theory of games and economic behavior.

Do you like this article? Follow me Be notified of my future publications.

(Tagstotranslate) Selection editors

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER