Recent years have shown amazing growth in deep learning neural networks (DNNs). This growth can be seen in more accurate models and even opening new possibilities with generative AI: large language models (LLMs) that synthesize natural language, text-to-image generators, and more. These increased capabilities of DNNs come with the cost of having massive models that require significant computational resources in order to be trained. Distributed training addresses this problem with two techniques: data parallelism and model parallelism. Data parallelism is used to scale the training process over multiple nodes and workers, and model parallelism splits a model and fits them over the designated infrastructure. Amazon SageMaker distributed training jobs enable you with one click (or one API call) to set up a distributed compute cluster, train a model, save the result to Amazon Simple Storage Service (Amazon S3), and shut down the cluster when complete. Furthermore, SageMaker has continuously innovated in the distributed training space by launching features like heterogeneous clusters and distributed training libraries for data parallelism and model parallelism.

Efficient training on a distributed environment requires adjusting hyperparameters. A common example of good practice when training on multiple GPUs is to multiply batch (or mini-batch) size by the GPU number in order to keep the same batch size per GPU. However, adjusting hyperparameters often impacts model convergence. Therefore, distributed training needs to balance three factors: distribution, hyperparameters, and model accuracy.

In this post, we explore the effect of distributed training on convergence and how to use Amazon SageMaker Automatic Model Tuning to fine-tune model hyperparameters for distributed training using data parallelism.

The source code mentioned in this post can be found on the GitHub repository (an m5.xlarge instance is recommended).

Scale out training from a single to distributed environment

Data parallelism is a way to scale the training process to multiple compute resources and achieve faster training time. With data parallelism, data is partitioned among the compute nodes, and each node computes the gradients based on their partition and updates the model. These updates can be done using one or multiple parameter servers in an asynchronous, one-to-many, or all-to-all fashion. Another way can be to use an AllReduce algorithm. For example, in the ring-allreduce algorithm, each node communicates with only two of its neighboring nodes, thereby reducing the overall data transfers. To learn more about parameter servers and ring-allreduce, see Launching TensorFlow distributed training easily with Horovod or Parameter Servers in Amazon SageMaker. With regards to data partitioning, if there are n compute nodes, then each node should get a subset of the data, approximately 1/n in size.

To demonstrate the effect of scaling out training on model convergence, we run two simple experiments:

Each model training ran twice: on a single instance and distributed over multiple instances. For the DNN distributed training, in order to fully utilize the distributed processors, we multiplied the mini-batch size by the number of instances (four). The following table summarizes the setup and results.

| Problem type | Image classification | Binary classification | ||

| Model | DNN | XGBoost | ||

| Instance | ml.c4.xlarge | ml.m5.2xlarge | ||

| Data set |

(Labeled images) |

Direct Marketing (tabular, numeric and vectorized categories) |

||

| Validation metric | Accuracy | AUC | ||

| Epocs/Rounds | 20 | 150 | ||

| Number of Instances | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Distribution type | N/A | Parameter server | N/A | AllReduce |

| Training time (minutes) | 8 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Final Validation score | 0.97 | 0.11 | 0.78 | 0.63 |

For both models, the training time was reduced almost linearly by the distribution factor. However, model convergence suffered a significant drop. This behavior is consistent for the two different models, the different compute instances, the different distribution methods, and different data types. So, why did distributing the training process affect model accuracy?

There are a number of theories that try to explain this effect:

- When tensor updates are big in size, traffic between workers and the parameter server can get congested. Therefore, asynchronous parameter servers will suffer significantly worse convergence due to delays in weights updates [1].

- Increasing batch size can lead to over-fitting and poor generalization, thereby reducing the validation accuracy [2].

- When asynchronously updating model parameters, some DNNs might not be using the most recent updated model weights; therefore, they will be calculating gradients based on weights that are a few iterations behind. This leads to weight staleness [3] and can be caused by a number of reasons.

- Some hyperparameters are model or optimizer specific. For example, the XGBoost official documentation says that the

exactvalue for thetree_modehyperparameter doesn’t support distributed training because XGBoost employs row splitting data distribution whereas theexacttree method works on a sorted column format. - Some researchers proposed that configuring a larger mini-batch may lead to gradients with less stochasticity. This can happen when the loss function contains local minima and saddle points and no change is made to step size, to optimization getting stuck in such local minima or saddle point [4].

Optimize for distributed training

Hyperparameter optimization (HPO) is the process of searching and selecting a set of hyperparameters that are optimal for a learning algorithm. SageMaker Automatic Model Tuning (AMT) provides HPO as a managed service by running multiple training jobs on the provided dataset. SageMaker AMT searches the ranges of hyperparameters that you specify and returns the best values, as measured by a metric that you choose. You can use SageMaker AMT with the built-in algorithms or use your custom algorithms and containers.

However, optimizing for distributed training differs from common HPO because instead of launching a single instance per training job, each job actually launches a cluster of instances. This means a greater impact on cost (especially if you consider costly GPU-accelerated instances, which are typical for DNN). In addition to AMT limits, you could possibly hit SageMaker account limits for concurrent number of training instances. Finally, launching clusters can introduce operational overhead due to longer starting time. SageMaker AMT has specific features to address these issues. Hyperband with early stopping ensures that well-performing hyperparameters configurations are fine-tuned and those that underperform are automatically stopped. This enables efficient use of training time and reduces unnecessary costs. Also, SageMaker AMT fully supports the use of Amazon EC2 Spot Instances, which can optimize the cost of training up to 90% over on-demand instances. With regards to long start times, SageMaker AMT automatically reuses training instances within each tuning job, thereby reducing the average startup time of each training job by 20 times. Additionally, you should follow AMT best practices, such as choosing the relevant hyperparameters, their appropriate ranges and scales, and the best number of concurrent training jobs, and setting a random seed to reproduce results.

In the next section, we see these features in action as we configure, run, and analyze an AMT job using the XGBoost example we discussed earlier.

Configure, run, and analyze a tuning job

As mentioned earlier, the source code can be found on the GitHub repo. In Steps 1–5, we download and prepare the data, create the xgb3 estimator (the distributed XGBoost estimator is set to use three instances), run the training jobs, and observe the results. In this section, we describe how to set up the tuning job for that estimator, assuming you already went through Steps 1–5.

A tuning job computes optimal hyperparameters for the training jobs it launches by using a metric to evaluate performance. You can configure your own metric, which SageMaker will parse based on regex you configure and emit to stdout, or use the metrics of SageMaker built-in algorithms. In this example, we use the built-in XGBoost objective metric, so we don’t need to configure a regex. To optimize for model convergence, we optimize based on the validation AUC metric:

We tune seven hyperparameters:

- num_round – Number of rounds for boosting during the training.

- eta – Step size shrinkage used in updates to prevent overfitting.

- alpha – L1 regularization term on weights.

- min_child_weight – Minimum sum of instance weight (hessian) needed in a child. If the tree partition step results in a leaf node with the sum of instance weight less than

min_child_weight, the building process gives up further partitioning. - max_depth – Maximum depth of a tree.

- colsample_bylevel – Subsample ratio of columns for each split, in each level. This subsampling takes place once for every new depth level reached in a tree.

- colsample_bytree – Subsample ratio of columns when constructing each tree. For every tree constructed, the subsampling occurs once.

To learn more about XGBoost hyperparameters, see XGBoost Hyperparameters. The following code shows the seven hyperparameters and their ranges:

Next, we provide the configuration for the Hyperband strategy and the tuner object configuration using the SageMaker SDK. HyperbandStrategyConfig can use two parameters: max_resource (optional) for the maximum number of iterations to be used for a training job to achieve the objective, and min_resource – the minimum number of iterations to be used by a training job before stopping the training. We use HyperbandStrategyConfig to configure StrategyConfig, which is later used by the tuning job definition. See the following code:

Now we create a HyperparameterTuner object, to which we pass the following information:

- The XGBoost estimator, set to run with three instances

- The objective metric name and definition

- Our hyperparameter ranges

- Tuning resource configurations such as number of training jobs to run in total and how many training jobs can be run in parallel

- Hyperband settings (the strategy and configuration we configured in the last step)

- Early stopping (

early_stopping_type) set toOff

Why do we set early stopping to Off? Training jobs can be stopped early when they are unlikely to improve the objective metric of the hyperparameter tuning job. This can help reduce compute time and avoid overfitting your model. However, Hyperband uses an advanced built-in mechanism to apply early stopping. Therefore, the parameter early_stopping_type must be set to Off when using the Hyperband internal early stopping feature. See the following code:

Finally, we start the automatic model tuning job by calling the fit method. If you want to launch the job in an asynchronous fashion, set wait to False. See the following code:

You can follow the job progress and summary on the SageMaker console. In the navigation pane, under Training, choose Hyperparameter tuning jobs, then choose the relevant tuning job. The following screenshot shows the tuning job with details on the training jobs’ status and performance.

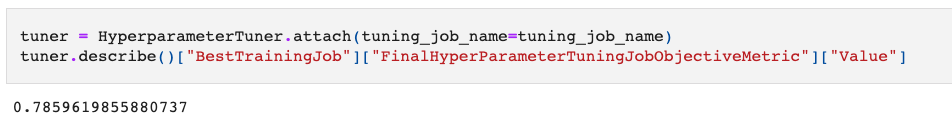

When the tuning job is complete, we can review the results. In the notebook example, we show how to extract results using the SageMaker SDK. First, we examine how the tuning job increased model convergence. You can attach the HyperparameterTuner object using the job name and call the describe method. The method returns a dictionary containing tuning job metadata and results.

In the following code, we retrieve the value of the best-performing training job, as measured by our objective metric (validation AUC):

The result is 0.78 in AUC on the validation set. That’s a significant improvement over the initial 0.63!

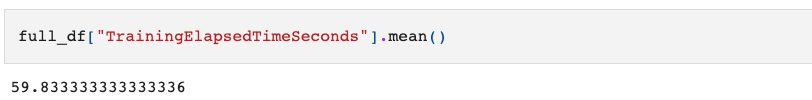

Next, let’s see how fast our training job ran. For that, we use the HyperparameterTuningJobAnalytics method in the SDK to fetch results about the tuning job, and read into a Pandas data frame for analysis and visualization:

Let’s see the average time a training job took with Hyperband strategy:

The average time took approximately 1 minute. This is consistent with the Hyperband strategy mechanism that stops underperforming training jobs early. In terms of cost, the tuning job charged us for a total of 30 minutes of training time. Without Hyperband early stopping, the total billable training duration was expected to be 90 minutes (30 jobs * 1 minutes per job * 3 instances per job). That is three times better in cost savings! Finally, we see that the tuning job ran 30 training jobs and took a total of 12 minutes. That is almost 50% less of the expected time (30 jobs/4 jobs in parallel * 3 minutes per job).

Conclusion

In this post, we described some observed convergence issues when training models with distributed environments. We saw that SageMaker AMT using Hyperband addressed the main concerns that optimizing data parallel distributed training introduced: convergence (which improved by more than 10%), operational efficiency (the tuning job took 50% less time than a sequential, non-optimized job would have taken) and cost-efficiency (30 vs. the 90 billable minutes of training job time). The following table summarizes our results:

| Improvement Metric | No Tuning/Naive Model Tuning Implementation | SageMaker Hyperband Automatic Model Tuning | Measured Improvement |

| Model Quality (Measured by validation AUC) |

0.63 | 0.78 | 15% |

| Cost (Measured by billable training minutes) |

90 | 30 | 66% |

| Operational efficiency (Measured by total running time) |

24 | 12 | 50% |

In order to fine-tune with regards to scaling (cluster size), you can repeat the tuning job with multiple cluster configurations and compare the results to find the optimal hyperparameters that satisfy speed and model accuracy.

We included the steps to achieve this in the last section of the notebook.

References

[1] Lian, Xiangru, et al. “Asynchronous decentralized parallel stochastic gradient descent.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2018.

[2] Keskar, Nitish Shirish, et al. “On large-batch training for deep learning: Generalization gap and sharp minima.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.04836 (2016).

[3] Dai, Wei, et al. “Toward understanding the impact of staleness in distributed machine learning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.03264 (2018).

[4] Dauphin, Yann N., et al. “Identifying and attacking the saddle point problem in high-dimensional non-convex optimization.” Advances in neural information processing systems 27 (2014).

About the Author

Uri Rosenberg is the AI & ML Specialist Technical Manager for Europe, Middle East, and Africa. Based out of Israel, Uri works to empower enterprise customers to design, build, and operate ML workloads at scale. In his spare time, he enjoys cycling, hiking, and complaining about data preparation.

Uri Rosenberg is the AI & ML Specialist Technical Manager for Europe, Middle East, and Africa. Based out of Israel, Uri works to empower enterprise customers to design, build, and operate ML workloads at scale. In his spare time, he enjoys cycling, hiking, and complaining about data preparation.