The term “quiet quitting” (sometimes called soft quitting or silent resignation) became a corporate buzzword and a cultural phenomenon in 2022 in the wake of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

This supposed wave of workplace passivity came riding the coattails of the Great Resignation and the newly reinvigorated labor-rights movement in the United States, but just what exactly does it mean, and is it really a new phenomenon?

What does actually “quiet quitting” mean?

Quiet quitting has been framed in different ways by different pundits, but it essentially boils down to doing only the required tasks associated with one’s job and not going “above and beyond” one’s job description. In other words, it is the middle ground between underperforming and overperforming.

Culturally, it is seen as a rejection of the hustle-culture mentality that has long been associated with career success and corporate ladder-climbing. In a functional sense, from an employee standpoint, it means not allowing more of one’s labor to be extracted by an employer than they are paying for.

However you spin it, quiet quitting seems to be a real phenomenon—and one that’s not going anywhere any time soon. In fact, according to a 2022 Gallup poll, more than half of American workers qualified as “quiet quitters.”

Is quiet quitting a misnomer?

The phrase “quiet quitting” seems to imply that an individual is voluntarily leaving their job (perhaps without giving their employer notice, hence the “quiet” part). Since the term actually translates to “doing exactly what one is required to do—no more, no less,” it certainly seems like a misnomer.

However, many opponents of quiet quitting don’t take the phrase literally, instead treating it as creative hyperbole, taking the stance that a lack of overachievement and enthusiasm at work translates to stalled personal and professional development and a dead-end career path.

According to Arianna Huffington, co-founder of the Huffington Post, for example, “we need to keep it out of our work lives … Quiet quitting isn’t just about quitting on a job, it’s a step toward quitting on life.”

What do business leaders think about the quiet quitting movement?

While many CEOs and old-school achievers seem to frown on the concept, others in the business world seem to view the quiet quitting trend as a natural and healthy development in a changing corporate landscape.

Steve Taplin, cofounder and CEO of Sonatafy Technology, for instance, described the phenomenon as “a movement in which employees become more in control of their schedule and begin prioritizing personal over professional duties.” To Taplin, the prioritization of a healthy work-life balance seems to be an issue of sustainability. He goes on to describe the trend as “the modern generation’s answer to burnout.”

Elon Musk, notoriously divising CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, seems to lean in the opposite direction. After acquiring microblogging site Twitter (now rebranded as X) in October 2022, Musk sent an email to all employees in which he wrote, “Going forward, to build a breakthrough Twitter 2.0 and succeed in an increasingly competitive world, we will need to be extremely hardcore … This will mean working long hours at high intensity. Only exceptional performance will constitute a passing grade.”

Overall, employers seem to be somewhat split on the quiet quitting concept, with some (like Musk) pushing back at it and others (like Taplin) realizing the movement is likely representative of a larger shift in the employer-employee power dynamic that will need to be adapted to as workplace norms continue to evolve.

Is quiet quitting really a new phenomenon?

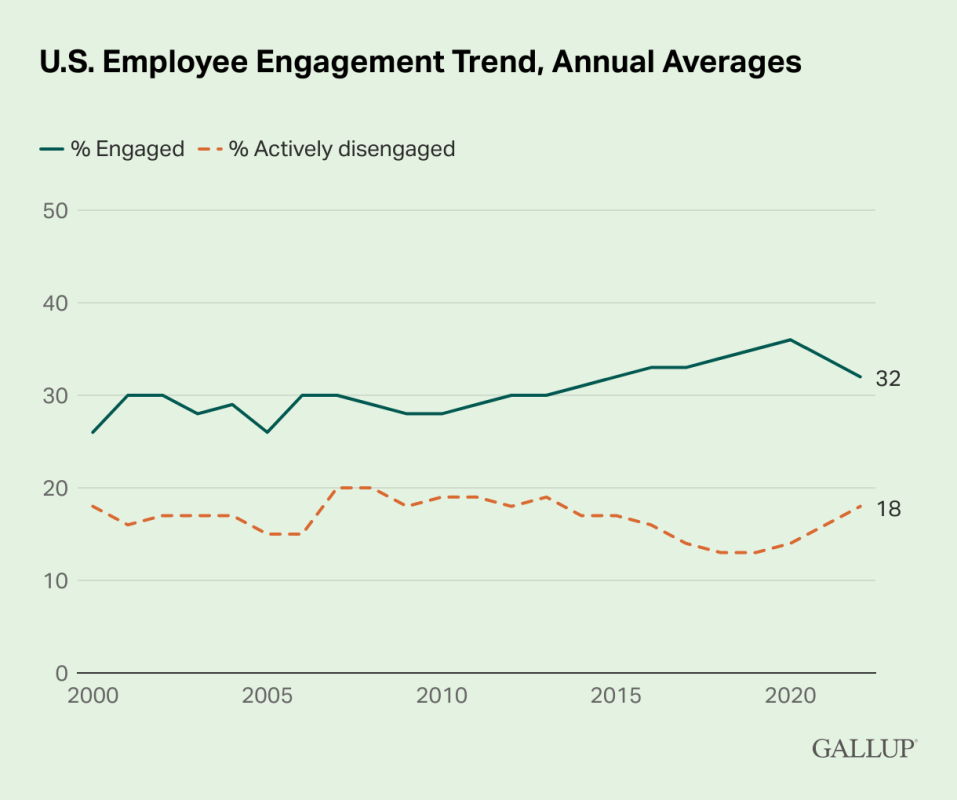

While the coined phrase and its viral nature might be new, actual data suggest quiet quitting is anything but a new movement. A Gallup poll of worker engagement (the same one referenced above) shows that employee engagement remained relatively stable between 2000 and 2022, actually going up slightly over that period.

That being said, there is a visible decline in the measure between 2020 and 2022, but it’s not a major decline, and it coincides with the onset and development of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The graphs below suggest that while quiet quitting is very real, and it may be a new cultural phenomenon, it is by no means a new statistical phenomenon.

Is quiet quitting good or bad?

On one hand, quiet quitting has been described by proponents as maintaining healthy boundaries and a sustainable work-life balance—doing what you’re paid for while prioritizing your mental health and personal priorities. On the other hand, it’s been characterized by its opponents as “checking out” while doing the bare minimum to collect a paycheck. So, which is it? That seems to be a matter of perspective.

Quiet quitting seems to be discussed with a negative connotation in much of the media, and for employers, maybe it is a bad thing—after all, the more labor a company can use above and beyond what it is paying for, the lower its costs, and the higher its profits.

For employees, on the other hand, quiet quitting has its pros and its cons. If an employee thinks of themself as a business (one that sells time and effort to an employer for money), quiet quitting simply means not giving that product away for free, which is just good business, especially if that product is in demand.

On the other side of the coin, employees who are actively trying to get promotions and raises may find quiet quitting an ineffective way to achieve these ends, as historically, overperforming without additional pay has been considered the best way to qualify for new roles and higher pay—although these are never guaranteed.

Quiet quitting as a labor rights issue

From a labor-rights perspective, an individual’s labor is a product like any other, and like all products, it costs money. Employees sell their time and effort (i.e., labor) to employers. Employers purchase this labor with pay, and the terms of that transaction are typically outlined in some sort of contract or job description.

Functionally, quiet quitting is simply an employee fulfilling the terms of that contract and receiving the agreed-upon pay. When an employee completes tasks (or spends time) above and beyond what is specified in their job description, they are, in a sense, giving away a product (their labor) for free.

The kicker is that employee labor is usually not a consumer-facing product—it exists further up the supply chain, meaning that it is used in the production of an end-product or service that is consumer-facing and is sold for a profit by the laboring individual’s employer. The profits that result from this unpaid labor are not typically shared with the employee, so in essence, an employee is giving away an asset (their time or effort) if they choose to do extra work or spend extra time at work without additional pay.

Where did the term “quiet quitting” come from? Who coined it?

“Quiet quitting” first hit the internet in March 2022 when a Gen-X career coach and employment influencer named Brian Creely used the phrase when discussing an Insider article about employees “coasting” at work. After that, the phrase went viral on TikTok, particularly among the app’s younger, Gen-Z-dominated user base.

Many discussions of the term also reference a movement that emerged in China in 2021 dubbed tang ping, which means “lying flat.” The tang ping movement is characterized by a rejection of societal pressure to work long, hard hours at the detriment of one’s well-being—essentially the equivalent of the quiet quitting movement in the U.S.