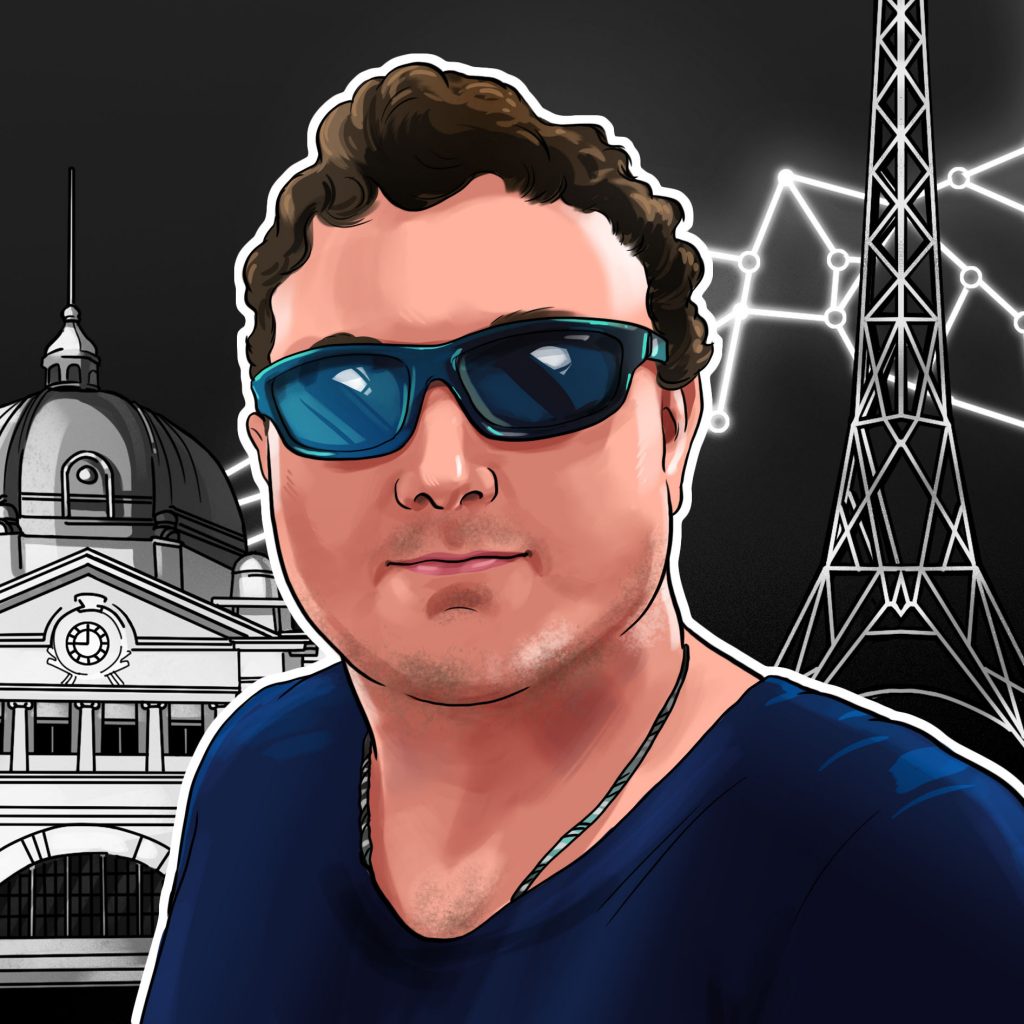

From his childhood living in a ghetto on the east bank of the Yamuna river in Dehli to launching the $6-billion Polygon blockchain, Sandeep Nailwal has an incredible rags-to-riches tale.

Now happily ensconced in the futuristic, air-conditioned cityscape of Dubai, he tells Magazine he was born in a farming village in 1987 with no electricity called Ramnagar in the foothills of the Himalayas.

His parents married as teenagers and then packed up home when Nailwal was just four to try their luck in Dehli. They wound up in the poor settlements on the east banks of the river, often dismissively referred to as Jamna-Paar.

“Imagine the Bronx in New York,” Nailwal says. “It was like a tier-three area. Even now, when you go there is a very kind of ghetto-ish area.”

He remembers lots of cows roaming the roads and illegal guns, though he says knives were the weapon of choice. “When stuff needs to be done, then knife is the best tool,” he says of the attitude.

Nailwal didn’t attend school until he was five, in a country and period where many schools accepted children as young as two and a half, mainly because his parents didn’t know any better.

“My father and mother both were kind of like illiterate people; they did not even realize that the kid should be sent to a school after three years or whatever. So, somebody in my area who used to have a small school said: ‘Why is your kid not going to school?’ And then I started going to school.”

He waves at an ordinary-sized room behind him in Dubai, saying the school was “almost the same size” with 20 kids crammed in. Home life wasn’t much better.

“My father became an alcoholic and got into gambling. So, he would make like $80 to $90 a month, and out of that, generally many times, he would lose all of it,” says Nailwal. As a result, the family was often behind on paying the school’s monthly fees, “so they will make you stand outside, and it’s basically a very traumatic experience as a kid.”

Also read: ZK-rollups are ‘the endgame’ for scaling blockchains: Polygon Miden founder

Experiences like that in his formative years helped Nailwal understand the kind of man he didn’t want to be and forge his determination to succeed. Now the head of his own family, with a young child named Adi, he says becoming a dad made him reflect on how he hopes to do things better than his own father. But the conversation takes a surprising turn when Nailwal reveals he was actually thrust into a paternal caring role, looking after his baby brother when he was just 10.

“I would say in a way, my first son is my own brother,” he says, his voice becoming thick with emotion. “So, basically, when he was very young, he met with an accident at that point in time. So, I would say that’s where my childhood ended basically because I had to take care of him.”

Young entrepreneur

Nailwal got his start in business as a teenager, selling pens from a friend’s shop at a decent markup in school and tutoring other students. After he graduated, he hoped to take an insanely competitive engineering exam for the Indian Institutes of technology (IIT) but couldn’t afford the extra tuition he needed to get an edge among “1 million students fighting for around 5,000 seats.”

He ended up getting accepted into the tier-two MAIT college in Dehli and took out a loan to put himself through a computer science and engineering degree.

Supremely ambitious and possibly a tad overconfident, he saw his future going down two possible paths based on two notable role models: Either join a company and work his way up to become “global CEO” like PepsiCo’s Indra Nooyi or start up a revolutionary internet business like Mark Zuckerberg did with Facebook.

“I was inspired by all this hype around Facebook in 2004, 2005,” he says, recalling the intense media coverage of Zuckerberg in India at the time. “I said to myself — and it was very stupid at that time — like I want to build my own Facebook. That’s why I chose computer science.”

During his university degree, his talents in data analysis saw him get a gig working on electorate analysis work for the regional BJP party — now India’s ruling party. After a short stint in the workforce after university, he returned to study at the National Institute for Training in Industrial Engineering (now the Indian Institute of Management) to get his MBA, where he met his wife, Harshita Singh.

Although a highly regarded employee at Deloitte, and then Welspun textiles, where he was quickly promoted to head of technology for e-commerce, Nailwal never stopped working on his own projects. He’d spend all day at work, then go home and work on projects like a GPS-based system to optimize cargo vehicle deliveries or a B2B service platform for project management.

Nailwal says he felt he wasn’t able to pursue a startup full-time, as he felt cultural pressure and a responsibility to get his family out of the one-bedroom rental they were in and into their own home. And nobody would give a home loan to a 27-year-old with intermittent income from a fledgling business.

But Harshita one day said, “You will never be happy this way,” he recalls. “She said, ‘I don’t care about my own house; we can stay and rent.’ That was a very big burden away from me.”

In his last month of work, he borrowed $15,000 so he could afford to pay for a wedding one day, and then started to work on the B2B services marketplace full time, which he ran for a year until he realized it would never scale up the way he wanted.

bitcoin revolution

Instead, he looked to get into “deep tech,” first considering then abandoning ai as it was beyond his mathematical abilities. bitcoin was starting to get some press at that time due to the upcoming halving in 2016.

Nailwal had heard about bitcoin back in 2013 but initially wrote it off as “some sort of Ponzi scheme.” After discovering it had lasted the distance, he thought it worthy of further investigation. Reading the “beautifully written” white paper, he realized:

“Oh, this is big — this is the next revolution of humanity.”

Converted, he was desperate to get “skin in the game” and, over the next three months, tipped the $15,000 wedding loan into bitcoin at $800 a piece. Looking back, he says it was an insanely risky move given his finances at the time.

“The level of FOMO I had, it would have been exactly the same if I was one year late. And I would have done the same thing at $20,000. Yeah, and I would have lost all that money, and it would have been really, really problematic for me.”

But as a builder, he wanted blockchain to be about more than just payments, which led him to ethereum’s full programmability. “I was like this is the thing, this is the thing I want,” he says.

Throwing himself into the space, Nailwal founded a blockchain services startup called Scope Weaver in 2016 and became well-known as a moderator on local ethereum forums. That’s where he met a “hardcore programmer” named Jaynti “JD” Kanan, who kept suggesting he spend his $400,000 bitcoin stash investing in his startup ideas.

Initially, Nailwal wasn’t keen, but then ethereum started to struggle with its own popularity during the 2017 bullrun, most notably after a 600% increase in transaction fees from CryptoKitties made the blockchain all but unusable.

Also read: ethereum is eating the world — ‘You only need one internet’

Kanan suggested they work on fixing ethereum’s scaling problems by developing the layer-2 Plasma technology proposed by Vitalik Buterin and Joseph Poon in August that year, which helped offload transactions to faster and less crowded side chains. Nailwal agreed and helped raise $30,000 in seed funding to build a product, with Anurag Arju joining as another co-founder and Matic Network officially launching in early 2018. The project was bootstrapped on the smell of an oily rag. All up, he says, the Matic Network survived for its first two years on $165,000 of total funding.

Matic Network nearly dies

Having watched endless projects raise millions with vaporware initial coin offerings, the team was determined not to launch a token sale until they had a product.

They would come to regret this decision bitterly. Launching directly into the great crypto market crash of early 2018, the ICO market was strong for a few months after but petered out by the time their runway was growing short.

“We kind of ignored that opportunity,” he says. “Which was really, really painful later on.”

Read also

Features

How to prepare for the end of the bull run, Part 1: Timing

Features

US enforcement agencies are turning up the heat on crypto-related crime

“We had this huge opportunity of raising $10 million. We left it; we did not do it. And now we have no money to build. I remember that one time I had to almost beg one of the other founders of one project from India to grant us $50,000 so that we can run for three more months.”

Shortly before his marriage, Nailwal traveled to pitch to a Chinese fund that seemed keen to invest $500,000 in the struggling project. He recalls being delighted two days before his marriage, with a house full of guests, that everything was going to be OK.

“Everybody’s happy, and I’m also content that we will get $500,000 now (for Matic Network), and suddenly, bitcoin goes from $6,000 to $3,000. That fund after that simply said, ‘No, we will not invest now because we were going to invest 100 btc; now the value is half, so we are not investing.’”

Even worse, the project’s treasury was still in bitcoin and had also halved in value.

“That was a very traumatic experience for me around that point because I should not have speculated on this money, which is the company’s Treasury,” he says, meaning that he should have cashed out or turned it into stablecoins.

“So, I was really angry at myself, and this thing went away. By that time, we had like seven, eight, 10 people (in Matic). They are also (attending) my marriage, and we are enjoying it and all that but deep down, I know that ‘shit, we might not have this team in the next two, three months.’”

Binance is actually diligent

Toward the end of 2018 and early 2019, the opportunity came up to raise funds in an initial exchange offering on Binance Launchpad. While the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission thinks Binance is a bunch of cowboys who will accept any old bus pass as Know Your Customer verification, Nailwal says the exchange’s due diligence was possibly too diligent.

“Nobody believed that there could be a protocol coming from Indian co-founders. And there were two or three projects which turned out to be scams, and everybody was very wary,” he says. Matic ended up going through eight months of evaluation before getting the nod to raise $5.6 million in $300 lots to the winners of a ballot.

Nailwal says, “At that point in time, $5 million was a very good amount.”

“If Binance had said, ‘You can raise $1.5 million or $1 million,’ we would even settle for that because we had a struggle for survival. But once we launched on Binance, things became much better.”

That marked a turning point for Matic, which survived the 2020 pandemic market crash and grew from fewer than 1,000 daily users at the end of that year to surpass ethereum’s user numbers with 550,000 in October 2021. It also flipped ethereum’s transaction numbers that year, too. Rebranding as Polygon, it surged from a market cap of $87 million at the start of 2021 to almost $19 billion by the end of the year.

Nailwal was now one of the richest and most successful people in the cryptocurrency industry. But he wasn’t satisfied, by a long shot.

“Being in top 10, top 15 projects brings no satisfaction to me. It’s very clear in my mind that I want Polygon to have that kind of impact which ethereum and bitcoin have had.”

Look out for part two, which tells the story of how Polygon became one of the key players in the space and Nailwal’s plans to make it a top-3 project.

Subscribe

The most engaging reads in blockchain. Delivered once a

week.