After the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), large numbers of Americans are beginning to realize the dangers of fractional reserve banking. Reports show that SVB suffered a significant bank run after customers tried to withdraw $42 billion from the bank on Thursday. The following is a look at what fractional reserve banking is and why the practice can lead to economic instability.

The History and Dangers of Fractional Reserve Banking in the United States

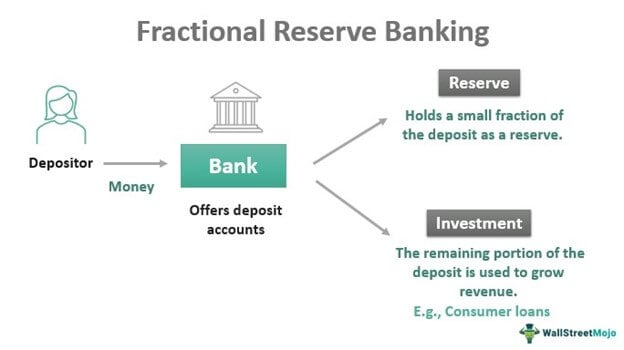

For decades, people have warned about the dangers of fractional-reserve banking, and the recent test by Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) has drawn attention to the issue. Essentially, fractional reserve banking is a bank management system that only holds a fraction of bank deposits, with the remaining funds invested or loaned to borrowers. Fractional Reserve Banking (FRB) operates in almost every country in the world, and in the US it became very prominent during the 19th century. Prior to this time, banks operated on full reserves, meaning they held 100% of their depositors’ funds on reserve.

However, there is considerable debate about whether installment loans happen these days, with some assuming invested funds and loans just print out of thin air. The argument is derived from a Bank of England document called “Creation of money in the modern economy.” It is often used to dispel myths associated with modern banking. Economist robert murphy analyzes these alleged myths in chapter 12 from his book, “Understanding the Mechanics of Money”.

The FRB practice spread significantly after the passage of the National Banking Act in 1863, which created the United States bank charter system. In the early 1900s, the fractional reserve method began to show cracks with bank failures and occasional financial crises. These became more prominent after World War I, and bank runs, featured in the popular movie “It’s a Wonderful Life,” became commonplace at the time. To fix the situation, a cabal of bankers called “The Money Trust” or “House of Morgan” worked with American bureaucrats to create the Federal Reserve System.

After more problems with fractional reserves, the Great Depression hit, and US President Franklin D. Roosevelt initiated the Banking Act of 1933 to restore confidence in the system. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was also created, which provides insurance to depositors who have $250,000 or less in a banking institution. Since then, the practice of fractional reserve banking has continued to grow in popularity in the US throughout the 20th century and remains the dominant form of banking today. Despite its popularity and widespread use, fractional reserve banking still poses a significant threat to the economy.

History of deposit limits from the FDIC. pic.twitter.com/e0q1NkzW6n

—Lyn Alden (@LynAldenContact) March 12, 2023

He major problem With fractional reserve banking there is the threat of a bank run because the banks only hold a fraction of the deposits. If a large number of depositors simultaneously demand the return of their deposits, the bank may not have enough cash on hand to meet those demands. This, in turn, causes a liquidity crisis because the bank is unable to appease depositors and could be forced to default on its obligations. A bank run can cause panic among other depositors who bank elsewhere. A major panic could have a ripple effect throughout the financial system, leading to economic instability and potentially causing a broader financial crisis.

“so it’s called fractional reserve banking”

“What is the fraction?”

“used to be 10% but now it’s 0” pic.twitter.com/iBbH6yxDXn

-foobar (@0xfoobar) March 12, 2023

Electronic banking and the speed of information may fuel the threat of financial contagion

In the movie It’s a Wonderful Life, news of insolvency spread through town like wildfire, but news of bank runs these days could be much faster due to several factors related to technological advances and speed. of the information. First, the Internet facilitated the rapid dissemination of information, and news about a bank’s financial instability can spread quickly through social media, news websites, and other online platforms.

Fractional reserve banking does NOT work, especially in the age of the internet and social media.

Information and fear spread too fast for an institution to react.

What used to take weeks now takes minutes.

A weak institution can be exposed and collapse in a matter of hours.

— The wolf of all streets (@scottmelker) March 12, 2023

Second, electronic banking has made transactions faster and people who want to withdraw can do so without physically going to the branch. The speed of online banking can lead to a faster and more widespread run on a bank if depositors perceive there is a risk that their funds will not be available.

Last, and perhaps the most important part of the current differences, is the interconnectedness of the global financial system, which means that a bank run in one country can quickly spread to other regions. The speed of information, electronic banking and the connected financial system could very well lead to a much faster and more widespread contagion effect than was possible in the past. While technological advances have made banking much more efficient and easier, these schemes have increased the potential for financial contagion and the speed at which a run on the bank can occur.

Hoax and ‘waves of credit bubbles with barely a fraction in reserve’

As mentioned above, many reputable market watchers, analysts, and economists have warned about the problems with fractional reserve banking. Even the creator of Bitcoin, Satoshi Nakamoto, wrote about the dangers in the seminal white paper: “The central bank must be trusted not to devalue the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is littered with breaches of that trust. Banks must be trusted to hold our money and transfer it electronically, but they lend it out in waves of credit bubbles with only a fraction in reserve,” Nakamoto wrote. This statement highlights the risk associated with fractional reserve banking, where banks lend more money than they have in reserves.

![]()

murray rothbard, an Austrian economist and libertarian, was a strong critic of fractional reserve banking. “Fractional reserve banking is inherently fraudulent, and if it were not subsidized and privileged by the government, it could not exist for long,” Rothbard once said. The Austrian economist believed that the fractional reserve system was based on deception and that banks created an artificial expansion of credit that could lead to economic booms followed by busts. The Great Recession of 2008 was a reminder of the dangers of fractional reserve banking, and it was the same year that Bitcoin was introduced as an alternative to traditional banking that does not rely on the trustworthiness of centralized institutions.

It is so strange how the United States suddenly woke up and realized what fractional reserve banking is.

—Erik Voorhees (@Erik Voorhees) March 12, 2023

The problems with SVB have shown that people have a lot to learn about these issues and about fractional banking in general. Currently, some Americans are calling on the Federal Reserve to bail out Silicon Valley Bank, hoping that the federal government will step in to help. However, even if the Fed saves the day on SVB, the dangers of fractional reserve banking still exist, and many use the SVB failure as an example of why one should not trust the banking system that operates accordingly. this way.

What steps do you think individuals and financial institutions should take to prepare for and mitigate the potential threat of financial contagion in today’s rapidly evolving digital landscape? Share your thoughts in the comments section below.

image credits: Shutterstock, Pixabay, Wiki Commons, Wall Street Mojo, It’s a Wonderful Life, Twitter

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only. It is not a direct offer or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, or a recommendation or endorsement of any product, service or company. bitcoin.com does not provide investment, tax, legal or accounting advice. Neither the company nor the author is responsible, directly or indirectly, for any damage or loss caused or alleged to be caused by or in connection with the use of or reliance on any content, goods or services mentioned in this article.