Amid the banking chaos of the 21st century, some look back more than 600 years to the Medici Bank, one of the most powerful banks of its day. It established its business and became one of the most respected banks in Europe during its prime, and the prominent Italian banking family were early adopters of fractional-reserve banking, a practice unknown to Medici Bank’s clients and eventually led to the failure of the institution.

‘Nothing New’: How the Medici Bank Failure Is Still Very Relevant to Modern Banking Practices Today

The collapse of three large banks in mid-March 2023 has caused people to scrutinize the risks of fractional reserve banking. The practice of fractional reserve banking is essentially when a financial institution holds only a fraction of the deposits in the bank, with the remaining funds being used to lend or invest for a return. One of the first acquaintances examples of fractional reserve banking was the Medici Bank, founded in Florence, Italy, in 1397 by Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici.

In the first five years of operation, Medici Bank grew rapidly and, before the financial institution’s demise, established branches throughout Western Europe. Like early 20th century bankers such as JP Morgan, Jacob Schiff, Paul Warburg, and George F. Baker, members of the House of Medici were extremely powerful. The Medici Bank was known to be one of the largest commercial enterprises during the Renaissance, but it ultimately failed after nearly 100 years of operation.

Philip J. Weights, president of the Swiss Finance and Technology Association (SFTA), explained in a Linkedin Post 2015 how the weight of “excessive lending” and “insufficient reserves” led to the final demise of the bank. According to Raymond De Roover’s book “The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank (1397-1494)”, published in 1963, liquidity was a problem from the bank’s inception. De Roover’s book details that the Medicis’ reserves held less than 10% of the deposits due to the management skills of family members.

He 380 page book explains how the Medici Bank experienced a period of decline between 1463 and 1490 due to shady and corrupt banking practices. The fraudulent schemes caused several Medici branches to be liquidated and sold to other banks. De Roover argued that despite being a leading member of the House of Medici and a successful banker, Francesco Sassetti “was unable to prevent the disastrous liquidation of the Bruges, London and Milan branches”. De Roover’s book notes that large borrowing was a popular practice that brought high interest rates.

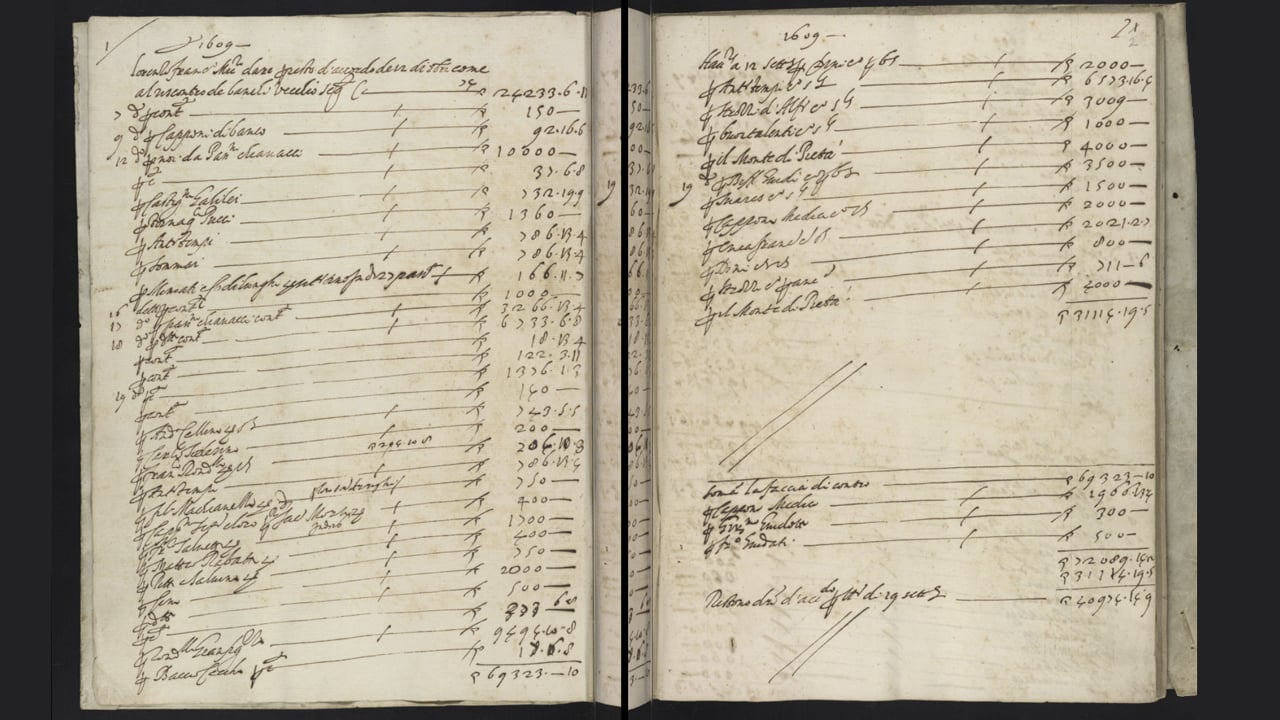

Florins, gold coins minted by the Republic of Florence, often featured on the balance sheet of the Medici Bank. However, the lack of reserves was a constant source of frustration for Medici’s banking partners as well as for government officials and clients alike. in a 2018 editorial At bigthink.com, author Mike Colagrossi detailed that “it was because of advances and financial solutions like these that the Medici bank became so powerful” as the Medici received high interest on the payments they lent. Colagrossi points out that the fall of the bank occurred after the death of Cosimo Medici in 1464who was the head of the bank at that time.

After the collapse of three large banks in 2023, jim white, president of Bianco Research, a firm that specializes in macro analysis for institutional investors, explained how fractional-reserve banking “was invented by the Medici in Florence in the late 15th century.” In its Twitter postBianco also mentions the scene from “two pence” in Disney’s 1960s musical film “Mary Poppins” and the bank run scene from “It’s a Wonderful Life” filmed in the 1930s, stating that “these are all still very relevant representations of what is happening today.”

White opined:

Nothing that is happening is new. Our banking system is several hundred years old and has constantly had these problems.

Triple Entry Accounting: A New Accounting System

Bianco also mentioned that double entry accounting it was the “technology” used to enable Medici Bank’s fractional reserve banking practices. The double entry scheme involves a ledger that records both debits and credits and is still in use in the modern financial world today. At that time, the Franciscan friar Luca Pacioli wrote a book on double-entry bookkeeping with aid of the well-known Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci. Although Pacioli and da Vinci did not claim to have invented the new system, their research led to a more extensive and structured use of double-entry bookkeeping that is still in use today.

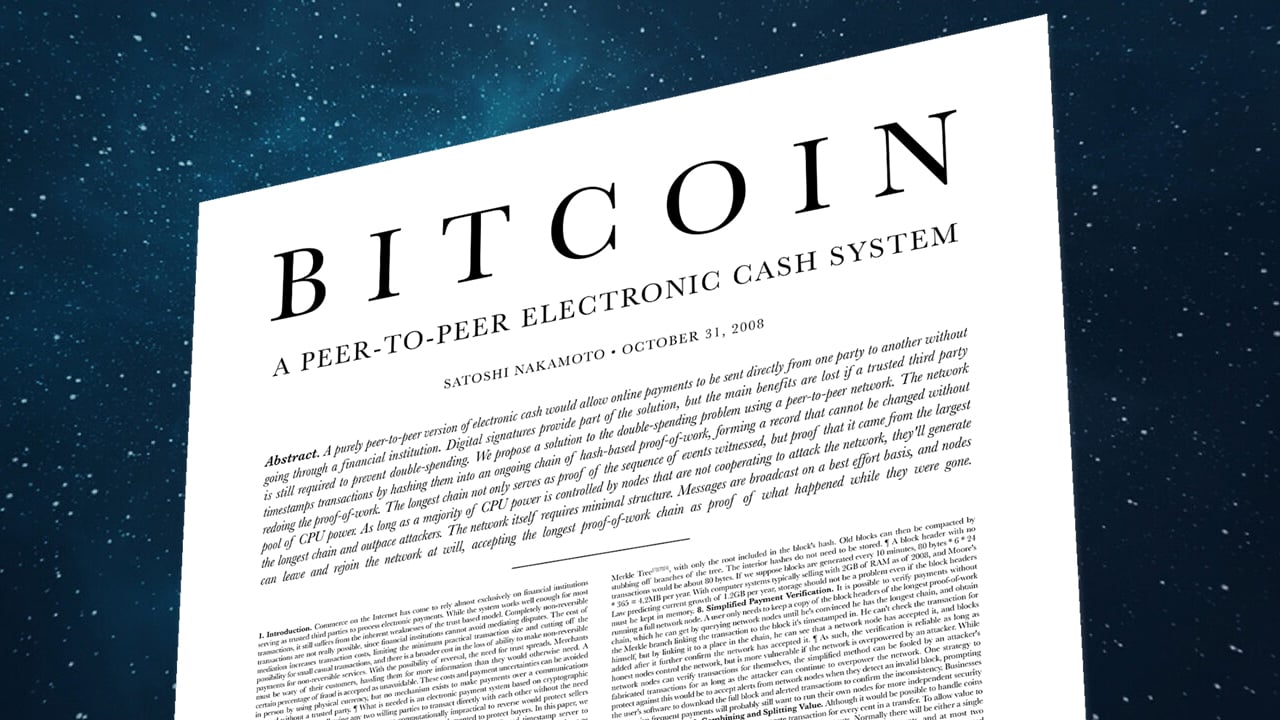

Shortly after the method became popular, Giovanni de Medici implemented the concept in his family’s bank. He allowed the House of Medici to operate with less than 10% of deposits and spread their lending practices far and wide until liquidity was completely depleted. More than 600 years later, an anonymous person or group published a paper who introduced the concept of triple entry bookkeeping. In addition to the debit and credit records, a third component has been added, which is a third-party verified cryptographic receipt to validate ledger entries.

Satoshi Nakamoto’s invention has produced a system where it is not necessary to rely on a double-entry bookkeeping system now that an improved ledger accounting scheme exists. A single-entry or double-entry ledger system can be falsified and manipulated, but adding fraudulent data to the cryptographic security of a triple-entry ledger system is much more difficult. While Bianco is correct that there is nothing new in the way bankers operate today, compared to the days of Medici, Nakamoto’s invention has given the world a new accounting method that can transform it a lot, like the invention of double entry. accounting has done.

What lessons can be learned from the fall of the Medici Bank? Share your thoughts in the comments section below.

image credits: Shutterstock, Pixabay, Wiki Commons

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only. It is not a direct offer or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, or a recommendation or endorsement of any product, service or company. bitcoin.com does not provide investment, tax, legal or accounting advice. Neither the company nor the author is responsible, directly or indirectly, for any damage or loss caused or alleged to be caused by or in connection with the use of or reliance on any content, goods or services mentioned in this article.