Sponsored Content

By Jim Dowling, Co-Founder & CEO, Hopsworks

This article introduces a unified architectural pattern for building both Batch and Real-Time machine learning (ML) Systems. We call it the FTI (Feature, Training, Inference) pipeline architecture. FTI pipelines break up the monolithic ai/dictionary/ml-pipeline” rel=”noopener” target=”_blank”>ML pipeline into 3 independent pipelines, each with clearly defined inputs and outputs, where each pipeline can be developed, tested, and operated independently. For a historical perspective on the evolution of the FTI Pipeline architecture, you can read the full ai/post/mlops-to-ml-systems-with-fti-pipelines” rel=”noopener” target=”_blank”>in-depth mental map for MLOps article.

In recent years, Machine Learning Operations (ai/mlops-dictionary” rel=”noopener” target=”_blank”>MLOps) has gained mindshare as a development process, inspired by DevOps principles, that introduces automated testing, versioning of ML assets, and operational monitoring to enable ai/dictionary/ml-systems” rel=”noopener” target=”_blank”>ML systems to be incrementally developed and deployed. However, existing MLOps approaches often present a complex and overwhelming landscape, leaving many teams struggling to navigate the path from model development to production. In this article, we introduce a fresh perspective on building ML systems through the concept of FTI pipelines. The FTI architecture has empowered countless developers to create robust ML systems with ease, reducing cognitive load, and fostering better collaboration across teams. We delve into the core principles of FTI pipelines and explore their applications in both batch and real-time ML systems.

The FTI approach for this architectural pattern has been used to build hundreds of ML systems. The pattern is as follows – a ML system consists of three independently developed and operated ML pipelines:

- a feature pipeline that takes as input raw data that it transforms into features (and labels)

- a training pipeline that takes as input features (and labels) and outputs a trained model, and

- an inference pipeline that takes new feature data and a trained model and makes predictions.

In this FTI, there is no single ML pipeline. The confusion about what the ML pipeline does (does it feature engineer and train models or also do inference or just one of those?) disappears. The FTI architecture applies to both batch ML systems and real-time ML systems.

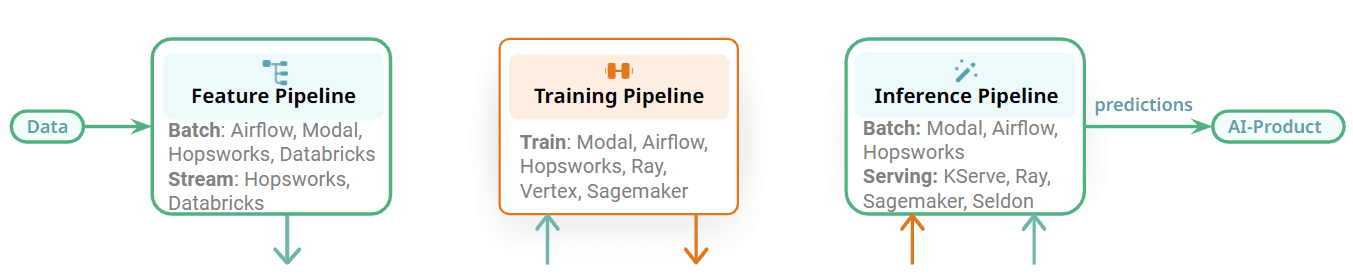

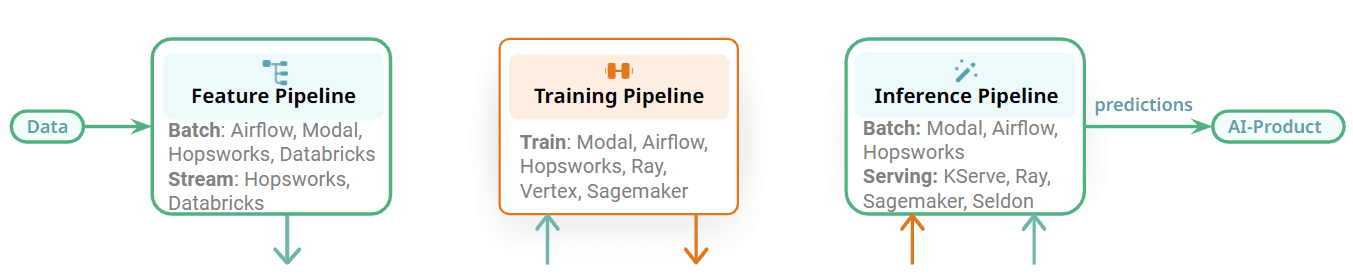

Figure 1: The Feature/Training/Inference (FTI) pipelines for building ML Systems

The feature pipeline can be a batch program or a streaming program. The training pipeline can output anything from a simple XGBoost model to a parameter-efficient fine-tuned (PEFT) large-language model (LLM), trained on many GPUs. Finally, the inference pipeline can be a batch program that produces a batch of predictions to an online service that takes requests from clients and returns predictions in real-time.

One major advantage of FTI pipelines is that it is an open architecture. You can use Python, Java or SQL. If you need to do feature engineering on large volumes of data, you can use Spark or DBT or Beam. Training will typically be in Python using some ML framework, and batch inference could be in Python or Spark, depending on your data volumes. Online inference pipelines are, however, nearly always in Python as models are typically training with Python.

Figure 2: Choose the best orchestrator for your ML pipeline/service.

The FTI pipelines are also modular and there is a clear interface between the different stages. Each FTI pipeline can be operated independently. Compared to the ai/dictionary/monolithic-ml-pipeline” rel=”noopener” target=”_blank”>monolithic ML pipeline, different teams can now be responsible for developing and operating each pipeline. The impact of this is that for orchestration, for example, one team could use one orchestrator for a feature pipeline and a different team could use a different orchestrator for the batch inference pipeline. Alternatively, you could use the same orchestrator for the three different FTI pipelines for a batch ML system. Some examples of orchestrators that can be used in ML systems include general-purpose, feature-rich orchestrators, such as Airflow, or lightweight orchestrators, such as Modal, or managed orchestrators offered by feature platforms.

Some of the FTI pipelines, however, will not need orchestration. Training pipelines can be run on-demand, when a new model is needed. Streaming feature pipelines and online inference pipelines run continuously as services, and do not require orchestration. Flink, Spark Streaming, and Beam are run as services on platforms such as Kubernetes, Databricks, or Hopsworks. Online inference pipelines are deployed with their model on model serving platforms, such as KServe (Hopsworks), Seldon, Sagemaker, and Ray. The main takeaway here is that the ML pipelines are modular with clear interfaces, enabling you to choose the best technology for running your FTI pipelines.

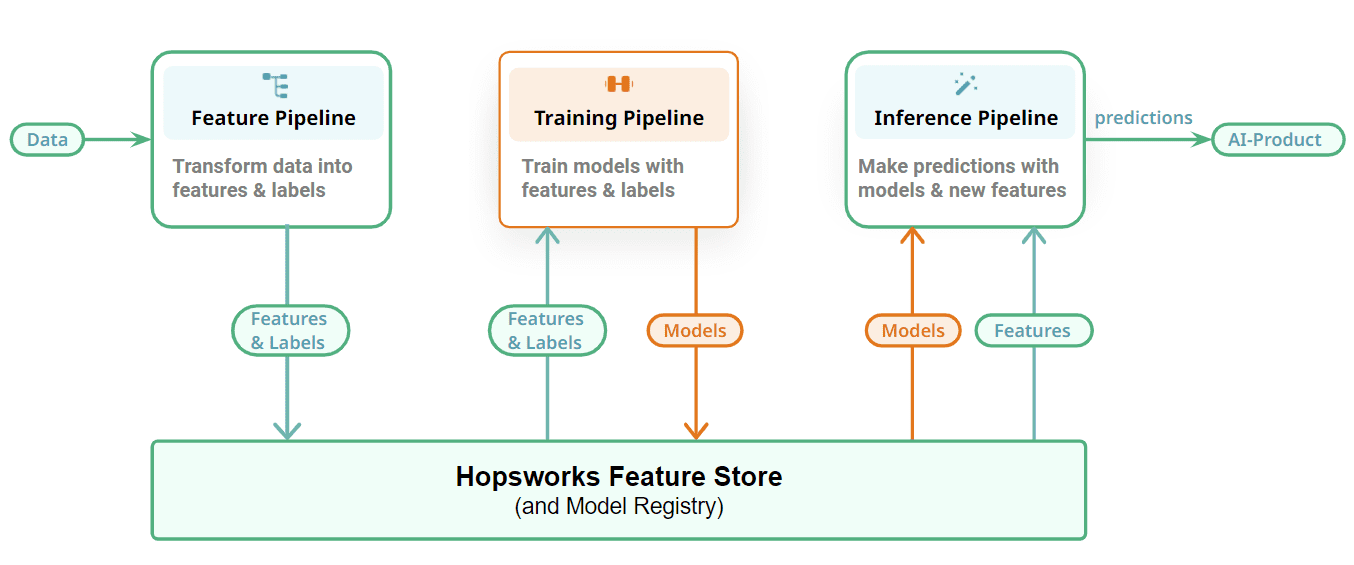

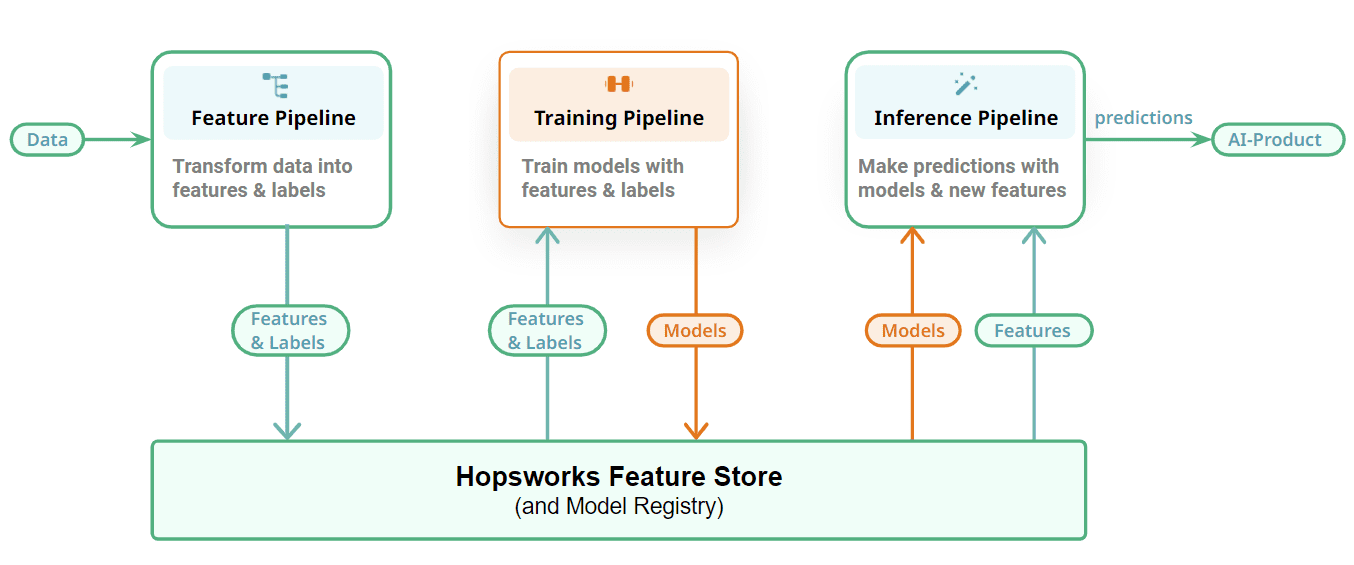

Figure 3: Connect your ML pipelines with a Feature Store and Model Registry

Finally, we show how we connect our FTI pipelines together with a stateful layer to store the ML artifacts – features, training/test data, and models. Feature pipelines store their output, features, as DataFrames in the feature store. Incremental tables store each new update/append/delete as separate commits using a table format (we use Apache Hudi in ai/the-ml-platform-for-batch-and-real-time-data” rel=”noopener” target=”_blank”>Hopsworks). Training pipelines read point-in-time consistent snapshots of training data from Hopsworks to train models with and output the trained model to a model registry. You can include your favorite model registry here, but we are biased towards Hopsworks’ model registry. Batch inference pipelines also read point-in-time consistent snapshots of inference data from the feature store, and produce predictions by applying the model to the inference data. Online inference pipelines compute on-demand features and read precomputed features from the feature store to build a ai/dictionary/feature-vector” rel=”noopener” target=”_blank”>feature vector that is used to make predictions in response to requests by online applications/services.

Feature Pipelines

Feature pipelines read data from data sources, compute features and ingest them to the feature store. Some of the questions that need to be answered for any given feature pipeline include:

- Is the feature pipeline batch or streaming?

- Are feature ingestions incremental or full-load operations?

- What framework/language is used to implement the feature pipeline?

- Is there data validation performed on the feature data before ingestion?

- What orchestrator is used to schedule the feature pipeline?

- If some features have already been computed by an upstream system (e.g., a data warehouse), how do you prevent duplicating that data, and only read those features when creating training or batch inference data?

Training Pipelines

In training pipelines some of the details that can be discovered on double-clicking are:

- What framework/language is used to implement the training pipeline?

- What experiment tracking platform is used?

- Is the training pipeline run on a schedule (if so, what orchestrator is used), or is it run on-demand (e.g., in response to performance degradation of a model)?

- Are GPUs needed for training? If yes, how are they allocated to training pipelines?

- What feature encoding/scaling is done on which features? (We typically store feature data unencoded in the feature store, so that it can be used for EDA (exploratory data analysis). Encoding/scaling is performed in a consistent manner training and inference pipelines). Examples of feature encoding techniques include scikit-learn pipelines or declarative transformations in ai/dictionary/feature-view” rel=”noopener” target=”_blank”>feature views (Hopsworks).

- What model evaluation and validation process is used?

- What model registry is used to store the trained models?

Inference Pipelines

Inference pipelines are as diverse as the applications they ai-enable. In inference pipelines, some of the details that can be discovered on double-clicking are:

- What is the prediction consumer – is it a dashboard, online application – and how does it consume predictions?

- Is it a batch or online inference pipeline?

- What type of feature encoding/scaling is done on which features?

- For a batch inference pipeline, what framework/language is used? What orchestrator is used to run it on a schedule? What sink is used to consume the predictions produced?

- For an online inference pipeline, what model serving server is used to host the deployed model? How is the online inference pipeline implemented – as a predictor class or with a separate transformer step? Are GPUs needed for inference? Is there a SLA (service-level agreements) for how long it takes to respond to prediction requests?

The existing mantra is that MLOps is about automating continuous integration (CI), continuous delivery (CD), and continuous training (CT) for ML systems. But that is too abstract for many developers. MLOps is really about continual development of ML-enabled products that evolve over time. The available input data (features) changes over time, the target you are trying to predict changes over time. You need to make changes to the source code, and you want to ensure that any changes you make do not break your ML system or degrade its performance. And you want to accelerate the time required to make those changes and test before those changes are automatically deployed to production.

So, from our perspective, a more pithy definition of MLOps that enables ML Systems to be safely evolved over time is that it requires, at a minimum, automated testing, versioning, and monitoring of ML artifacts. MLOps is about automated testing, versioning, and monitoring of ML artifacts.

Figure 4: The testing pyramid for ML Artifacts

In figure 4, we can see that more levels of testing are needed in ML systems than in traditional software systems. Small bugs in data or code can easily cause a ML model to make incorrect predictions. From a testing perspective, if web applications are propeller-driven airplanes, ML systems are jet-engines. It takes significant engineering effort to test and validate ML Systems to make them safe!

At a high level, we need to test both the source-code and data for ML Systems. The features created by feature pipelines can have their logic tested with unit tests and their input data checked with data validation tests (e.g., ai/post/data-validation-for-enterprise-ai-using-great-expectations-with-hopsworks” rel=”noopener” target=”_blank”>Great Expectations). The models need to be tested for performance, but also for a lack of bias against known groups of vulnerable users. Finally, at the top of the pyramid, ML-Systems need to test their performance with A/B tests before they can switch to use a new model.

Finally, we need to version ML artifacts so that the operators of ML systems can safely update and rollback versions of deployed models. System support for the push-button upgrade/downgrade of models is one of the holy grails of MLOps. But models need features to make predictions, so model versions are connected to feature versions and models and features need to be upgraded/downgraded synchronously. Luckily, you don’t need a year in rotation as a Google SRE to easily upgrade/downgrade models – platform support for versioned ML artifacts should make this a straightforward ML system maintenance operation.

Here is a sample of some of the open-source ML systems available built on the FTI architecture. They have been built mostly by practitioners and students.

Batch ML Systems

Real-Time ML System

This article introduces the FTI pipeline architecture for MLOps, which has empowered numerous developers to efficiently create and maintain ML systems. Based on our experience, this architecture significantly reduces the cognitive load associated with designing and explaining ML systems, especially when compared to traditional MLOps approaches. In corporate environments, it fosters enhanced inter-team communication by establishing clear interfaces, thereby promoting collaboration and expediting the development of high-quality ML systems. While it simplifies the overarching complexity, it also allows for in-depth exploration of the individual pipelines. Our goal for the FTI pipeline architecture is to facilitate improved teamwork and quicker model deployment, ultimately expediting the societal transformation driven by ai.

Read more about the fundamental principles and elements that constitute the FTI Pipelines architecture in our full ai/post/mlops-to-ml-systems-with-fti-pipelines” rel=”noopener” target=”_blank”>in-depth mental map for MLOps.