YoIf you’re heading to the Australian Center for the Moving Image (Acmi) in Melbourne right now, you can visit Out of limits, an exhibition that “explores the limits of video games”. There you can watch The Grannies: a documentary about four game developers and friends in Melbourne who, while playing as a group of elderly cowboys in the Playstation game Red Dead Redemption 2, went in search of adventure in the off-limits areas with failures beyond. the game map.

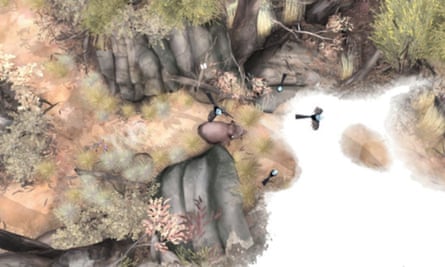

Alongside The Grannies at Acmi, attendees can play red desert render, which was created by game developer Ian MacLarty, one of the four grandmothers. Red Desert Render takes the experience of exploring strange and glitchy virtual spaces. It’s not unlike many of MacLarty’s other games, which are often free, very Australian and experimental, such as Southbank Portrait and kelly. But MacLarty is also a highly successful commercial game developer: his next game, First Mars Logisticsit takes all these weird space experiments and turns them into a highly polished commercial product.

When talking about games having cultural value in Australia, that value is usually measured by the amount of money they make ($284.4 million in 2021/2022, an increase of 26% on the previous year) or the number of jobs they create. But MacLarty’s career is a great example of why game development can’t be understood as an art form based on how much money they make alone. Like musicians, painters, writers, and all other artists, game developers develop a practice through constant experimentation, with only some projects evolving into something the general public will ever see.

It is exactly this kind of practice-based work that has rebuilt Australia’s video game industry after the devastation of the 2008 global financial crisis. In the early 2010s, Australia’s video game industry hit rock bottom, with numerous school closures and job losses, and the Abbott government removing the Australian Interactive Games Fund. But despite all this, game developers began to rebuild a strong national industry on the basis of mostly small independent teams. Australian games now regularly receive critical acclaim around the world, including Untitled Goose Game, paper barkUnpacking, frog detective and Cult of the Lamb. Slowly, the country has caught up: both the state and federal governments have introduced more funding and tax breaks, and cultural institutions like the National Film and Sound Archivesydney Electric power plant and Acmi in Melbourne treat gaming seriously as art.

In a tremendously significant milestone and a clear sign that the games are being recognized as an important contribution to Australian culture, the games were featured in the Albanian government’s new national cultural policy, Revive. Australia’s first national cultural policy in a decade he has promised more support in the arts, including video games, and has promised to bring back the Australian Interactive Games Fund that Abbott killed.

And yet, Revive’s language is revealing. The games are important because they “increase the economic contribution of Australia’s creative industries,” the report says, and because they can attract new audiences to other, more traditional art forms, such as classical music. This speaks to the longstanding and limited ways in which games are understood. Its ability to make money and its inherent youthful coolness are defended, but the complex ways in which games are themselves a crucial art form and are made by creators who are themselves artists. remain unrecognized.

after newsletter promotion

I don’t want to look a gift horse in the teeth. Undoubtedly, Revive marks a huge step forward for the recognition of gaming in Australian culture. But if they are to receive significant support in the future, game development must be treated as cultural work. This doesn’t just mean defending the games that make money, but also defending all the practice and experimentation that can sometimes lead to new innovations and success stories.

This is particularly critical, considering that one of Revive’s main pillars is to “support the artist as a worker”. That would require guarantees like minimum wages, workplace protections and safe working conditions, all of which Revive promises. But it also requires understanding, nurturing and supporting the unique and unpredictable work that goes into making art. There is no linear path to business success. There is no Mars First Logistics, no Untitled Goose Game, no Unpacking, without a lot of unpaid, unpredictable and seemingly “unproductive” creative work that must come first. And the challenge now, for governments and cultural institutions that want to grow the Australian video game industry, will be how they support that very intrinsically important work: art.

-

Dr. Brendan Keogh is Senior Lecturer in the School of Communication and Principal Investigator at the Digital Media Research Center at Queensland University of Technology. He is the author of the next book. The video game industry does not exist.